Introduction 2000 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Barnum, P. T. (Phineas Taylor), 1810-1891

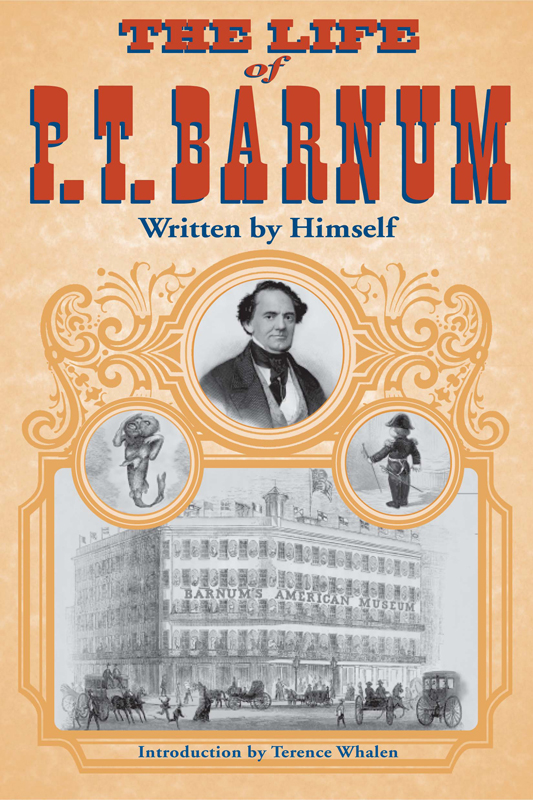

The life of P.T. Barnum / written by himself, Phineas T. Barnum;

introduction by Terence Whalen..

p. cm.

Originally published: New York : Redfield, 1855.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-252-06902-1 (paper : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-06902-4 (paper : alk. paper)

1. Barnum, P. T. (Phineas Taylor), 1810-1891.

2. Circus ownersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

GV1811.B3 A3 2000

791.3092dc21

[B]

99-462094

P 9 8 7 6 5

INTRODUCTION

P. T. Barnum and the Birth of Capitalist Irony

TERENCE WHALEN

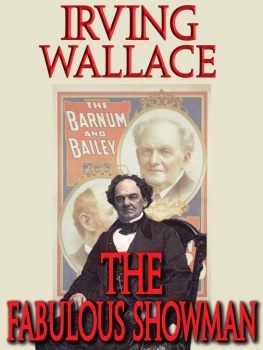

For more than fifty years, Phineas T. Barnum embodied all that was grand and fraudulent in American mass culture. His life spanned nearly the entire nineteenth century (1810-91), and during that period he inflicted himself upon a surprisingly willing public in a wide variety of roles. Barnums supporters pointed to his exemplary success as a newspaper editor, lottery agent, museum director, politician, traveling showman, and distinguished public benefactor. Barnums detractors, however, used different names to describe his meteoric career: libeler, swindler, huckster, demagogue, charlatan, and shameless hypocrite.

Barnum desired and deliberately fostered this ambiguous public image. He did so partly through a systematic (and lifelong) campaign of advertising, shrewdly exploiting the cultural and technological capabilities of the new publishing industry. He was also one of the more important popular authors of the nineteenth century. While running his numerous shows and exhibitions, Barnum managed to publish newspaper articles, exposs of fraud, self-help tracts, and, most notably, a series of best-selling autobiographies. The version offered here is the original 1855 Life of P. T. Barnum, Written by Himself , a book that scandalized a nation in its own era but has never since been reprinted in its entirety.

Barnum and the Age of Confidence

Barnum lived during one of the most tumultuous periods of expansion in American history. When he was born in 1810, the United States numbered seven million inhabitants; when Barnum published his autobiography in 1855, the population had nearly quadrupled to twenty-seven million; and at the time of Barnums death in 1891, it had risen to sixty-four million. These figures provide the demographic foundation for the famous dictumcommonly but erroneously ascribed to Barnumthat there was a sucker born every minute. The emerging nation was by no means homogeneous, but the growing population accelerated westward migration, the rise of cities, and the acquisition of new territory through purchase or conquest.

Historians have devised a variety of labels for the era described in Barnums Life . Following the practice of naming historical periods after political rulers, some have identified the time of Barnums apprenticeship as the Age of Jackson or of Jacksonian Democracy. Andrew Jackson, who served as president from 1829 to 1837, rode the crest of a populist swell by repeatedly affirming the virtues of the common man. In practice, that meant attacking the symbols of wealth and power while defendingor pandering tothe masses.

The Life of P. T. Barnum , however, suggests that antebellum culture had less to do with information than with what we now call disinformation. As a showman, Barnum was frequently accused of disseminating falsehood and immorality, and these accusations continued to plague him in his capacity as an autobiographer. Barnums position was especially difficult because autobiographies were an important staple of the new literary market and because his Life was sold alongside such exemplary texts as the Autobiography (1818) of Benjamin Franklin and the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass (1845). Both of these books were important in their day, and both are now regarded as canonical texts of the American literary tradition. Franklin, in an ironic and playful voice, focuses on personal shortcomings and recommends a course of action or self-making for individuals (exemplified by his famous list of virtues). Douglass, mingling autobiography with political and religious rhetoric, focuses on social conditions and advocates a course of action for the country as a whole (exemplified by the struggle to abolish slavery). In different ways, then, Franklin and Douglass both offer their life stories to promote a better world.

The Life of P. T. Barnum contrasts starkly with these model narratives, for it is largely indifferent to moral and social reform. Barnum playfully recounts his errors, but they are ascribed to a pervasive environment of humbug, and, unlike Douglass, Barnum sees no place for collective action. Barnums amoral perspective is unsettling, but it does afford certain advantages. By describing his profitable deceptions and schemes, Barnum reveals the problems of American mass culture in a way that Franklin and Douglass do not. And by offering an outlandish version of self-making and self-reliance, Barnum questions many ideas that are central to the American autobiographicaland politicaltradition.

Barnums contemporaries were nevertheless scandalized by his narrative. For many nineteenth-century reviewers, Barnums Life epitomized a growing flood of autobiographies that were spreading immorality and corruption throughout the land. There was a time when people must have lived lives before they could sell them, complained one reviewer, but now dead or alive, great or little, famous or infamousthe author of a code or the man who was hanged under iteveryone has his equal chances of a life.

In fact, Barnum took pains to emphasize how his early upbringing in Bethel, Connecticut, had prepared him for his later career as the Prince of Humbugs. The first six chapters of the Life comprise an extensive litany of petty frauds and practical jokes that the people of Bethel inflicted upon each other. On one occasion, for example, Barnums grandfather convinced a group of men sailing to New York to shave off half their beards at a time with his razorthe only razor on board. After they were all half-shaven and quite ludicrous in appearance, Barnums grandfather finished shaving himself and then accidentally dropped the razor into the sea. (When the ship reached New York, his companions attracted a rabble of onlookers as they marched single-file through the streets.) This same grandfather built up young Barnums hopes and pretensions with an ostensibly magnificent inheritance of land called Ivy Island, and Barnums parents colluded in perpetuating the boys dream. When Barnum was twelve, he discovered the joke that had been played on him: The truth rushed in upon me. I had been made a fool of by all our neighborhood for more than half a dozen years. My rich Ivy Island was an inaccessible piece of barren land, not worth a farthing, and all my visions of future wealth and greatness vanished into thin air (34).

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.