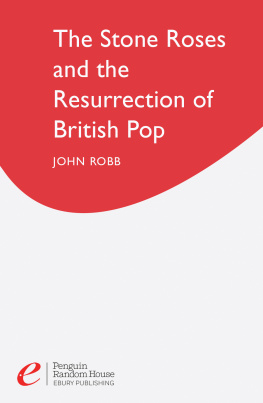

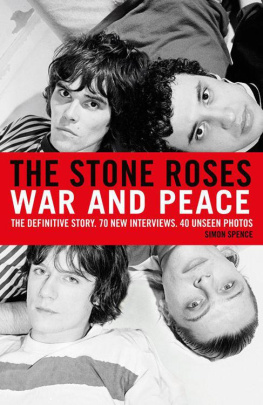

Copyright Mick Middles 1996

This electronic edition published in 2010 by Essential Works

http://www.essentialworks.co.uk

ISBN: 978-1-906615-06-2

The Author hereby asserts his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, expect by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

CONTENTS

1

ANARCHY IN TIMPERLEY

It began in Warrington, of all places that strange, flat cusp where Manchester shades into Liverpool in a muddle of business parks and featureless housing estates; a meeting place for Manc and Scouse, Cheshire and Lancashire. Unpromising ground for a musical phenomenon perhaps, and yet it was Warrington which saw the introduction of a radical new music to the north of England, one which foreshadowed the invasion of rocknroll in the Fifties. For it was at the local Birchwood Aerodrome, during the latter stages of World War Two, that off-duty American servicemen staged wild evenings of swing music, a magnetic maelstrom of sex, swagger and souped-up sound which drew in flocks of impressionable local girls, and frequently provoked violent confrontations with the comparatively unsophisticated local boys.

Ian George Brown, no stranger to violent confrontations himself, was born in Warrington on February 20, 1963, into an unpretentious, stable and loving family. His father, George, for whom Ian is allegedly a dead ringer, was a popular local joiner, laddish to a point but never one to lose himself in alcoholic revelry; Ians mother, Jean, worked as a telephone receptionist. Although today Brown describes his Warrington years as grim, he still harbours a couple of striking memories of his birthplace. For instance, if you are looking for an early indication of his infamous arrogance, his punkism, you might trace it back to the day he was unwillingly made milk monitor at his primary school. They gave me this title, milk monitor, and I think I was supposed to feel proud, he recalls. Took me about two seconds to realise that all it meant was that I had to hand all the milk out to all the other kids. I refused. Completely. Told the teacher that they should go and get their own milk. Damn right, too. Im still quite proud of that. Also, Brown recalls lying in some grass (aged four), staring at the sky, feeling belligerent. I had been taken out of school and this girl I was with, cant remember who she was, was telling me that I was bad. I dont know if I was proud or ashamed. But, from that age, yeah, I did have a rebellious streak.

When Brown was aged just six, the family moved to leafy Timperley, in the soft underbelly of Manchester. This represented a slight social upgrading although to date, Timperley remains a curious place, where the sprawling council estate of Wythenshaw fizzles out into the plush suburbs of Altrincham. No wonder that for school children thrown in from the two social extremes marked by big houses and little houses, gleaming BMWs and rusty Ford Escorts the eternal jarring of class can readily give rise to conflict. Naturally perhaps, the kids from the rougher end of the scale and Brown would fit into this category would become the cool ones, the ones driven to adorn themselves with the glittery prizes of social importance. (Which is why working-class school kids are traditionally regarded by their peers as the more stylish, the more streetwise, the more effortlessly hip.)

Brown had a younger brother, David, and a sister, Sharon, her name chosen by the young Ian in honour of Sharon McCready, the vivacious blonde from the Sixties TV show The Champions , and one of his first crushes. (His sister actually prefers to be known as Louise.) Though he chose to lock himself for hours on end in his poster-lined bedroom as a child, Ians early family life was uneventful and unproblematic, though those posters provide another clue to the Brown psyche. All of them featured the perfect, glowing figure of Muhammad Ali, the most charismatic sportsman of the century, a giant talent and a giant personality, a beautifully packaged dynamo with a wicked talent for wordplay. Brown adored Ali from the time when, only five years old, his young eyes first saw the great man on a television screen. The arrogance, the supreme power of self-confidence and the breathtaking style would all register and stay with Ian Brown, influencing his attitude to life and his style as a performer. He remains a boxing fan to this day.

And then there was the music. Music filled the Brown household. When he was eight, Ians aunt presented him with a stack of well worn seven-inch discs, inspirational slabs of plastic, which he would pile on his self-stacking Dansette, and listen to over and over again, soaking in their curious magic. Every dusty, scratched single was a classic: Its Not Unusual, Tom Jones; Help, The Beatles; Under My Thumb and Get Off My Cloud, The Rolling Stones; The Happening and Love Child by The Supremes. Each one brilliantly evocative, an inspirational vinyl experience, the power of which is unlikely ever to translate effectively onto soulless compact discs. Incidentally, three of those singles Help, Under My Thumb and Its Not Unusual were also stacked on the young Mick Hucknalls Dansette, seven miles away, across Manchester. This revelation, which emerged in separate interviews, should not be too surprising the power of the pop single in the Sixties and Seventies was far greater than it is today, when the impact of a song is muddied by the diversity of versions afforded by multi-formatting and the visual distractions of video. In an earlier era of pop, it was simply a question of sitting in the corner of a room and soaking up the sound of one golden track after another; for Ian Brown, music became education and inspiration.

It was to be the same story for one of Browns neighbours, who lived two doors down on Sylvan Avenue. John Thomas Squire was born on November 24, 1962, in Broadheath. The meeting of these two is already immersed in pop legend, as befits one of the most significant songwriting partnerships in recent memory the location a communal sand pit where the local children could play. The event is spiced further by Johns recollection that Ian was naked, save for a few patches of sand. Brown doesnt dispute this, but adds, If thats how John remembers it, then maybe it was like that. I do recall the sand pit. Used to muck around in there a lot. I remember meeting John probably quite a few times but we werent, like, dead close, because I had my own mates from school. But I do recall his shy stare, which was quite intriguing even then. There was something about him.

They attended separate primary schools with Brown apparently the classroom joker at his. He was always the one to grab the lead role in the classroom plays, always out front, openly mimicking the teacher; indeed, his repertoire of localised impressions covered the entire teaching staff. My best one? Mr Clarke, the maths teacher. He had a really gruff voice and when I did him I cracked everyone up, he told Q in 1998. Brown is under no illusions as to his disruptive influence on the rest of the class. A lot of the teachers were wary of me, cos I was always quick to answer back, he recalls, adding tellingly, not that I was particularly naughty, but I did have an attitude. I have never liked people telling me what to do. By contrast, John Squires primary school life saw him skulking firmly at the back of the class, dodging away from any trace of drama, deflecting any possibility of attention. His shyness masked a considerable intellect, a fact recognised only by the more perceptive teachers at his school. He excelled in art and, on games afternoons, would be allowed to mooch about in the deserted art room, quietly pursuing his creative instincts. Drawing sessions allowed him to display a striking faculty for concentrated work, and he spent many solitary hours developing his skills with the pencil even at the expense of friendships. At primary school he made few if any lasting friends, preferring to live in a semi-permanent dream state, much to the concern of his teachers.