DOUGLAS SMITH

RASPUTIN

MACMILLAN

To Stephanie

And to the memory of my father,

D. William Smith

(19292013)

Auch behauptet man: die Tlpel,

Als sie an das Meer gelangten

Und gesehn, wie sich der Himmel

In der blauen Fluth gespiegelt,

Htten sie geglaubt, das Meer

Sei der Himmel, und sie strzten

Sich hinein mit Gottvertrauen;

Seien smtlich dort ersoffen.

Heinrich Heine, Atta Troll, Caput XII

Its also said that these fools,

Upon reaching the ocean-shore

And having seen how the sky

Was reflected in the blue tide below,

Believed that the sea

Must be Heaven, and in they plunged,

With faith in God,

And all were drowned.

Author translation, based on Herman Scheffauer (1913)

Contents

List of Illustrations

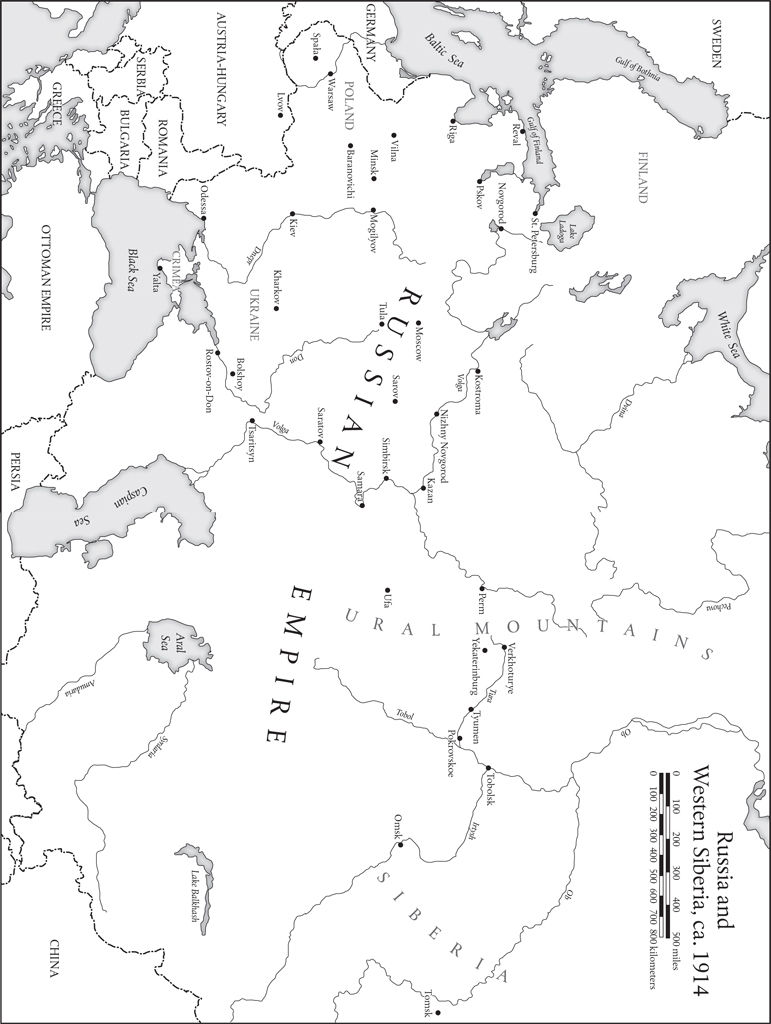

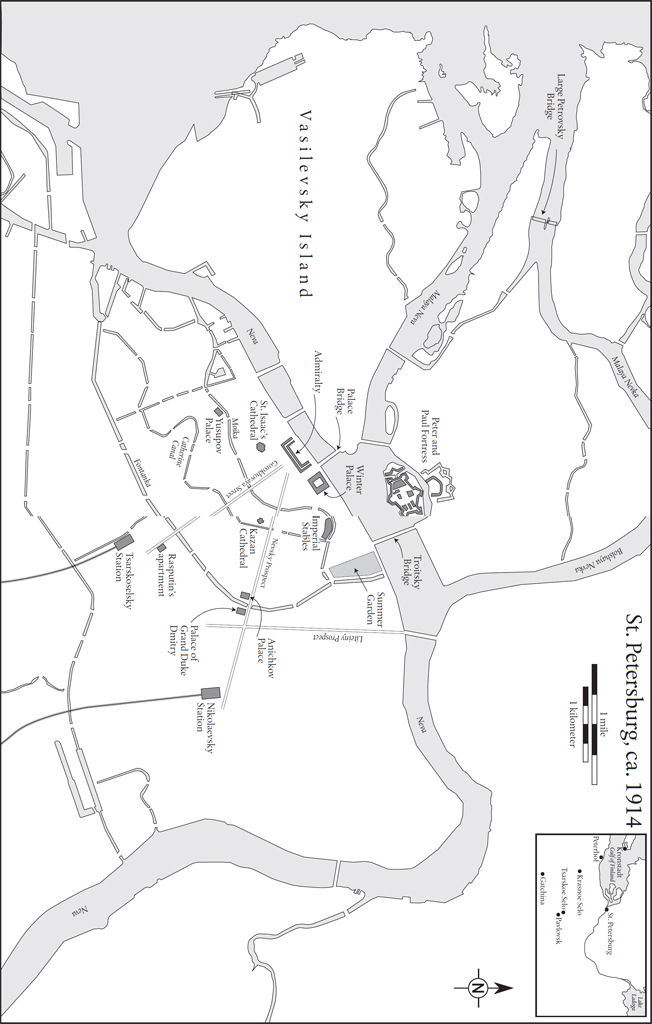

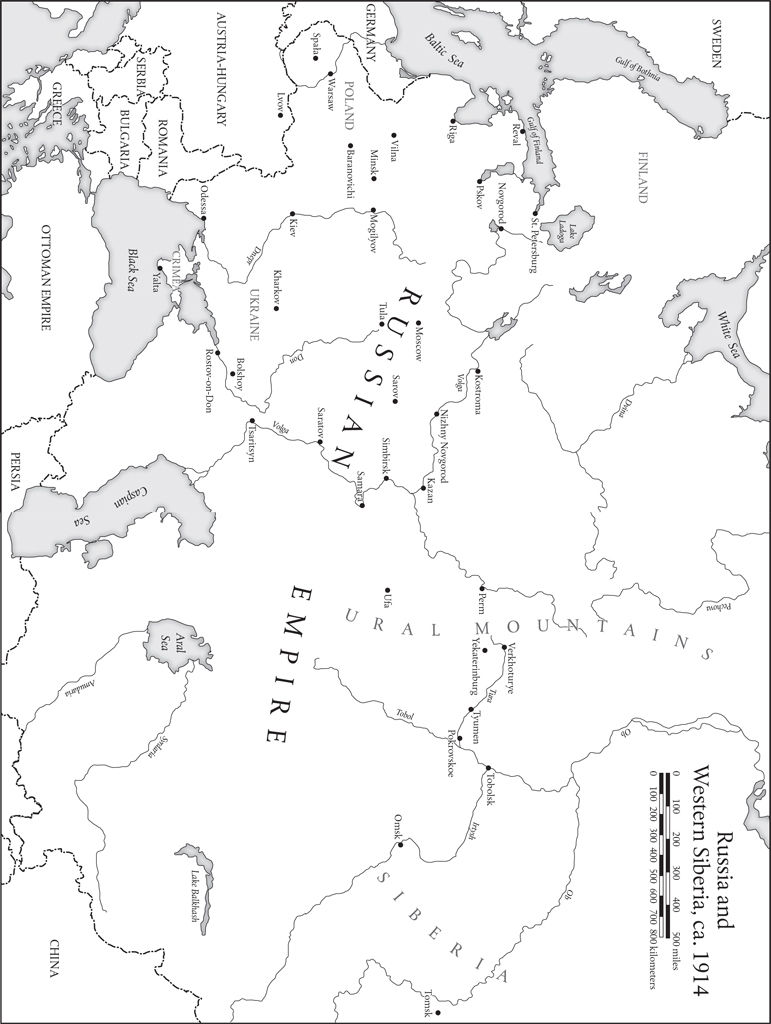

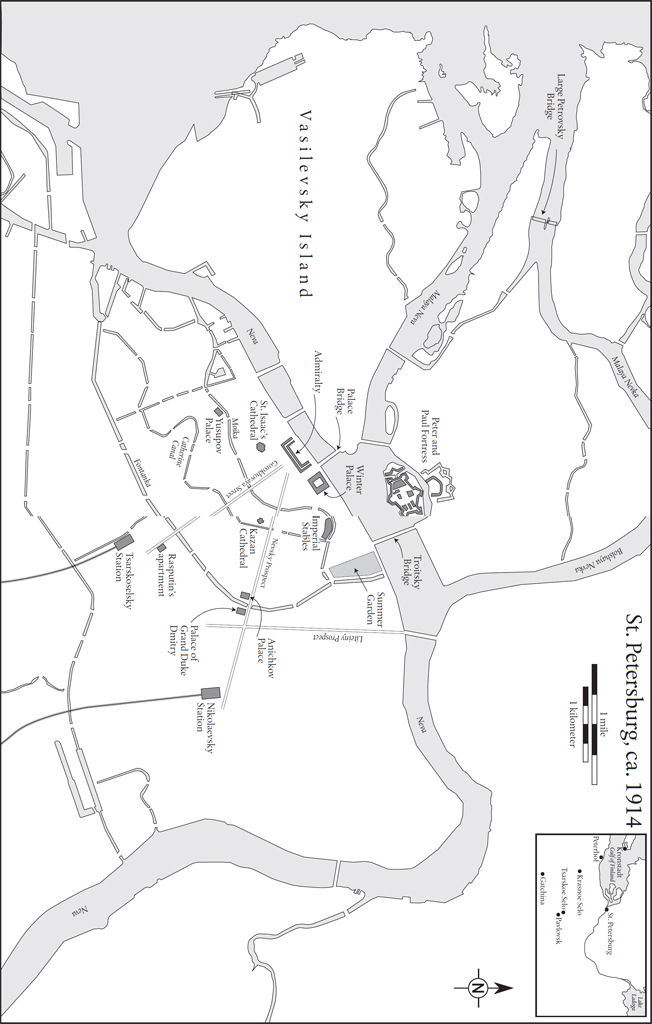

Maps

Note on Dates and Spelling

Before February 1918, Russia followed the Julian (Old Style) calendar that in the nineteenth century was twelve days (and in the twentieth century, thirteen days) behind the Gregorian (New Style) calendar used in the West. In January, the Bolshevik government decreed that Russia would adopt the Gregorian calendar at the end of the month, thus 31 January 1918 was followed the next day by 14 February. I have chosen to give Old Style dates for events in Russia before 31 January 1918 and New Style after that; wherever there is a chance for any confusion, I have added the notations OS or NS.

I have used a modified Library of Congress format for transliterating Russian words and names into English and have kept the masculine and feminine endings of Russian surnames (Grigory Rasputin, Maria Rasputina, for example). In cases where individuals are better known by the English versions of their names, such as Tsar Nicholas II, I have used these and not transliterations of the original.

Introduction: The Holy Devil?

On a bright spring day in 1912 Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky carried his large tripod camera down to the banks of the Tura River in the remote Siberian village of Pokrovskoe. One of the great photographic innovators of the age, Prokudin-Gorsky had developed a technique for taking vivid color photographs, images that so impressed Emperor Nicholas II of Russia, he commissioned the photographer to record his empire in all its diverse splendor.

His camera captured a typical rural scene that day. The white village church, bleached in the sun, rises above the simple houses and barns, crude log structures, brown and gray, gathered around it. On one of the houses a window box cradles a plant with red flowers, geraniums perhaps, highlighted against the dark panes. A pair of cows graze casually on the green shoots released from the earth after another long Siberian winter. At the waters edge, two women in colored dresses have been caught in their daily chores. A solitary boat rests in the mud, ready for the next fishing trip out into the Tura. The image recalls so many similar anonymous villages that Prokudin-Gorsky photographed in the final years of tsarist Russia.

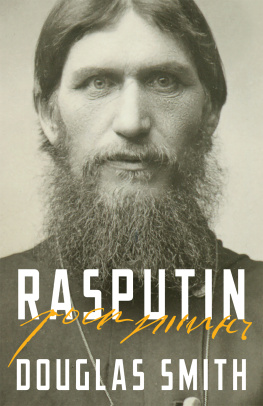

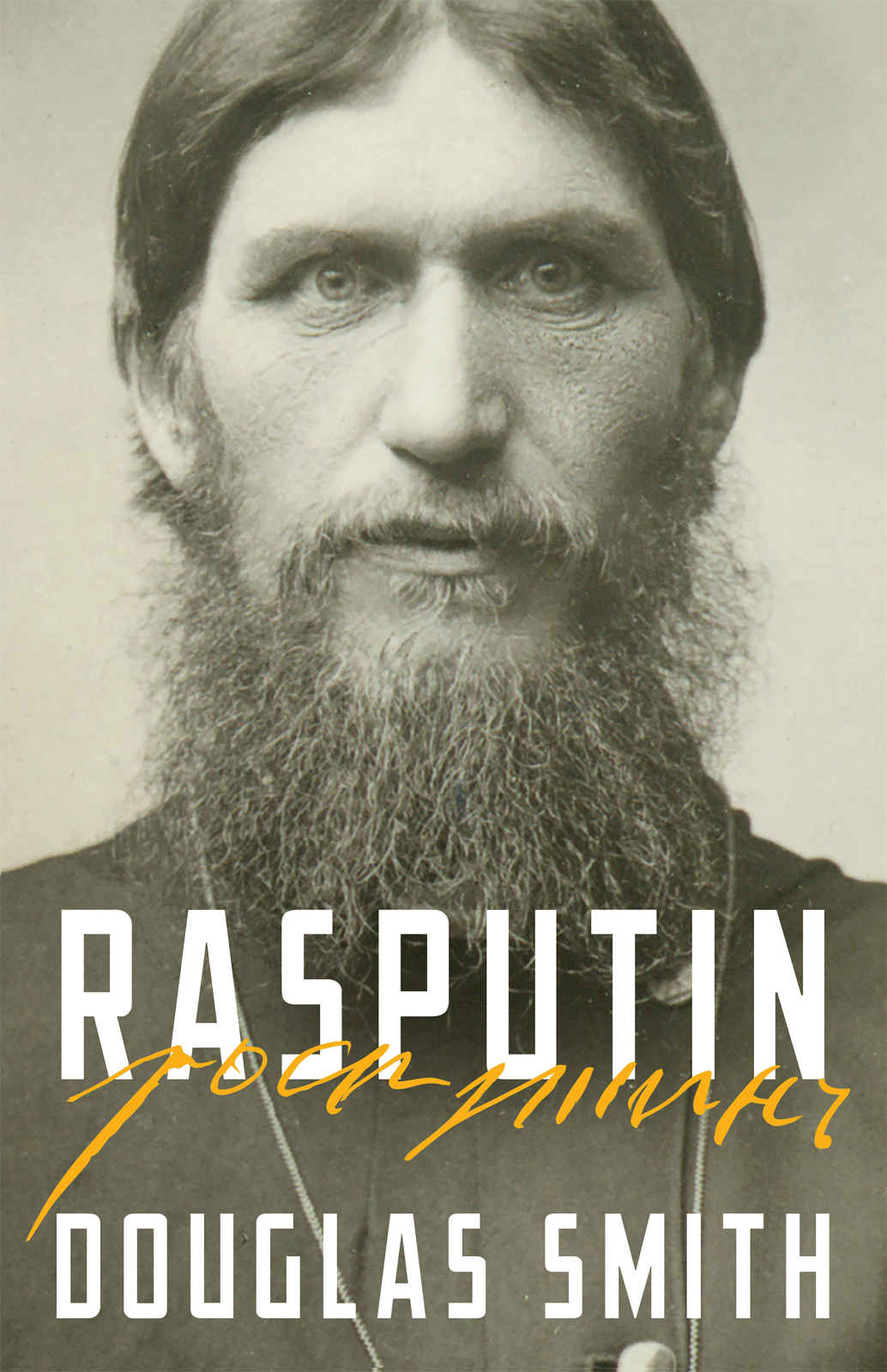

Yet this village was different from all the others, and Prokudin-Gorsky knew that the emperor and empress would expect him to include Pokrovskoe in his great survey. Pokrovskoe was the home of the most notorious Russian of the day, a man who in the spring of 1912 became the focus of a scandal that shook Nicholass reign like nothing before. Rumors had been circulating about him for years, but it was then that the tsars ministers and the politicians of the State Duma, Russias legislative assembly, first dared to call him out by name and demand that the palace tell the country who precisely this man was and clarify his relationship to the throne. It was said that this man belonged to a bizarre religious sect that embraced the most wicked forms of sexual perversion, that he was a phony holy man who had duped the emperor and empress into embracing him as their spiritual leader, that he had taken over the Russian Orthodox Church and was bending it to his own immoral designs, that he was a filthy peasant who managed not only to worm his way into the palace, but through deceit and cunning was quickly becoming the true power behind the throne. This man, many were beginning to believe, presented a real danger to the church, to the monarchy, and even to Russia itself. This man was Grigory Yefimovich Rasputin.

All of this must have been on the mind of Prokudin-Gorsky that day. This was not just any village he was photographing, it was the home of Rasputin. Prokudin-Gorsky captured Pokrovskoe for the tsar, but, curiously, he was careful not to include in his image the house of its most infamous son, which he left outside the frame. Perhaps this was the great photographers way of registering his own comment on the man Russia could not stop talking about.

The life of Rasputin is one of the most remarkable in modern history. It reads like a dark fairy tale. An obscure, uneducated peasant from the wilds of Siberia receives a calling from God and sets out in search of the true faith, a journey that leads him across the vast expanses of Russia for many years before finally bringing him to the palace of the tsar. The royal family takes him in and is bewitched by his piety, his unerring insights into the human soul, and his simple peasant ways. Miraculously, he saves the life of the heir to the throne, but the presence of this outsider, and the influence he wields with the tsar and tsaritsa, angers the great men of the realm and they lure him into a trap and kill him. Many believed that the holy peasant had foreseen his death and prophesied that should anything happen to him, the tsar would lose his throne. And so he does, and the kingdom he once ruled is plunged into unspeakable bloodletting and misery for years.

Even before his gruesome murder in a Petrograd cellar in the final days of 1916, Rasputin had become in the eyes of much of the world the personification of evil. His wickedness was said to recognize no bounds, just like his sexual drive that could never be sated no matter how many women he took to his bed. A brutish, drunken satyr with the manners of a barnyard animal, Rasputin had the inborn cunning of the Russian peasant and knew how to play the simple man of God when in front of the tsar and tsaritsa. He tricked them into believing he could save their son, the tsarevich Alexei, and with him the dynasty itself. They placed themselves, and the empire, in his hands, and he, through his greed and corruption, betrayed their trust, destroying the monarchy and bringing ruin to Russia.

Rasputin is possibly the most recognized name in Russian history. He has been the subject of dozens of biographies and novels, movies and documentaries, theatrical works, operas, and musicals. His exploits have been extolled in song, from The Three Keys jazzy 1933 Rasputin (The Highfalutin Lovin Man) to Boney Ms 1978 Euro-disco hit: Ra Ra Rasputin, lover of the Russian queen... Ra Ra Rasputin, Russias greatest love machine. There are countless Rasputin bars, restaurants, and nightclubs, there is Rasputin computer software (an acronym for Real-Time Aquisition System Programs for Unit Timing in Neuroscience), a comic book series, an action figure. He is the star of at least two video games (