Two Ways to Read

This book features art and animation specifically designed to enhance this story. You can control your experience on compatible devices by using the Show Media option in the Aa menu.

Mr. Nobody

There was a general panic, a great many excitable people declaring that the evil one was revisiting the earth.

H.M., anonymous East End missionary, 1888

M ONDAY, AUGUST 6, 1888, was a bank holiday, and London was a carnival of wondrous things to do for as little as pennies if one could spare a few. The bells of Windsors Parish Church and St. Georges Chapel rang all day. Ships were dressed in flags. Royal salutes boomed from cannons to celebrate the Duke of Edinburghs forty-fourth birthday. The Crystal Palace dazzled with every entertainment imaginable.

There were organ recitals, military band concerts, a monster display of fireworks, a grand fairy ballet, ventriloquists, world-famous minstrel performances, and horse and cattle shows. Madame Tussauds titillated with a special wax model of Frederick II lying in state and of course the ever-popular Chamber of Horrors. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was playing to sold-out houses, and the famous American actor Richard Mansfield was brilliant in the starring dual role at Henry Irvings Lyceum Theatre. The Opera Comique also had its version, a scandalous one because Robert Louis Stevensons novella had been adapted without permission.

Bazaars in Covent Garden overflowed with Sheffield Plate, gold, jewelry, and a vast variety of weapons and used clothing including military uniforms. If one wanted to pretend to be a soldier on this festive day, he could do so with little expense and no questions asked. That just might have appealed to a gifted impersonator like Walter Richard Sickert, a former actor whose stage name was Mr. Nemo. Nemo is Latin for nobody.

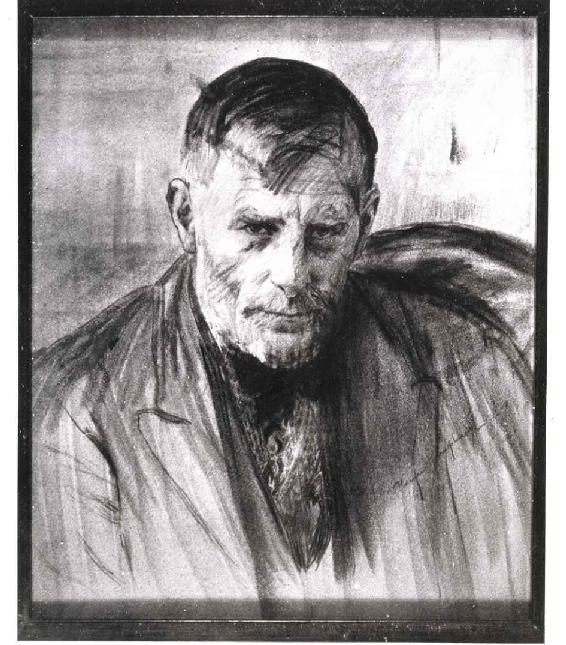

Twenty-eight-year-old Sickert had given up the theater for art and was a student of the American master James McNeill Whistler. At this time in Sickerts life he was an apprentice struggling for independence and his own place in the art world. He couldnt make a living. Hed been married three years, and his wife supported him as women always would. He was known for his striking good looks.

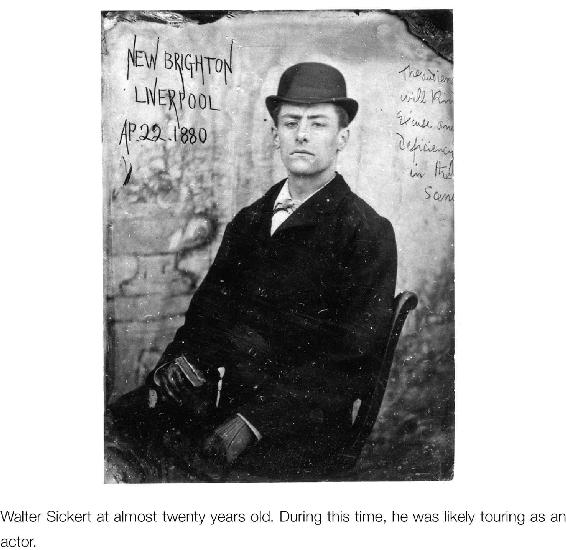

During what by now is a fifteen-year investigation into the Jack the Ripper case, Ive been able to find few early photographs of Sickert. But one taken when he was twenty shows a chiseled face with a perfectly angled nose and jaw, and thick wavy hair. He was blond with penetrating blue eyes, his features flawless and sensual except for his mouth. People who knew him described it as cruel .

He was slender, with a strong upper body from swimming, and considered a little above average in height. In those days that was about five foot seven for a man. Several pairs of his painting coveralls donated to the Tate Archive in the 1980s suggest he could have been as tall as five foot eight or nine. But it depends on whether he wore his pant legs short or long. That could make the difference of an inch or two. A caricature or doodle Whistler apparently dashed off of him in 1885 depicts Sickert as rail thin, long legged, slouching, loudly and cheaply dressed and predominantly right-handed.

Such details would become important when witnesses described men last seen with Jack the Rippers victims. But as I will explain later, the women he murdered were seen with many men on streets that had very poor lighting, and the Ripper was resourceful. I believe he was a chameleon. He could change his appearance including the color of his hair, his height and weight when he wanted to blend with his environment. Thats what disguises are for, and Sickert was fond of them onstage and off.

He was a master of greasepaint and wardrobe. As a child he was capable of completely transforming himself into someone else, usually a decrepit elderly man. In a letter Sickert wrote in 1880 to historian and biographer T. E. Pemberton, he described playing an old man in Henry V while on tour in Birmingham: It is the part I like best of all. He constantly changed his appearance with a variety of beards and mustaches. He was known for his bizarre hairstyles and clothing that in some instances were so outlandish they looked like costumes.

When the mood struck, he might shave his head or change his name. Onstage he was Mr. Nemo. In published articles and letters and in signatures on his art he was An Enthusiast, A Whistlerite , Your Art Critic, An Outsider, Walter Sickert, Sickert, Walter R. Sickert, Richard Sickert, W. R. Sickert, W.S., R.S., S., D., Dick, W. St., Rd. Sickert LL.D., R.St.W., R.St. A.R.A., and RdSt A.R.A.

He was a Proteus, wrote French artist and friend Jacques-mile Blanche. Sickerts genius for camouflage in dress, in the fashion of wearing his hair, and in his manner of speaking rival Fregolis. Sickert was described as having a great range of voice. He was proficient if not fluent in German, English, French and Italian. He knew Latin well enough to teach it to friends, and he was adept at Danish and Greek and possibly knew Portuguese and Spanish.

Such details were of interest when a team of scientists and I examined the only physical evidence that remains in the Ripper case, the hundreds of mockingly violent letters locked in the vaults of The National Archives and the London Metropolitan Archives. Not all of the letters the Ripper allegedly wrote to the media and the police are in English. They are rife with artistic media and drawings. The handwriting wildly varies. Much of it is obviously disguised.

Sickert was a skilled draftsman. He could write his name backward in cursive. He could write in perfect copperplate script or calligraphy or illegibly or any way he wanted. He may have been ambidextrous. Its said that he liked to read the classics in their original languages, but he didnt always finish a book once he started it. Usually there were dozens of them scattered about, opened to the last page that had caught his interest. Not much did unless it somehow affected him. Walter Sickert was center stage of his own drama. He never hesitated to admit he was pathologically selfish.

Today he would be diagnosed a psychopath, a narcissist. Typical of people with personality disorders, he had compulsions, and the media was one of them. He was addicted to newspapers, tabloids and journals. Throughout his life his studios looked like a recycling center for just about every bit of newsprint to roll off the European presses. If it struck his fancy he might dabble with newspapers from the United States or as far away as Australia.

He was a graphomaniac, firing off so many articles for newspapers and journals that he would apologize to whomever he submitted them to. Its likely he sent anonymous letters to the editor, using pseudonyms including his former stage name, Nemo. His correspondence with acquaintances and friends was compulsive but not warm or hinting of any genuine interest in their lives or well-being. He was charming and witty but attention-seeking, snide, nosy, gossipy and a voyeur. He didnt seem to have a habit of saving letters from anyone including his family, his wives or his mentors such as Whistler. But its hard to say. So much has vanished. Its impossible to know what might have been destroyed by the people who have protected him.

Next page