Copyright 2007 Omnibus Press

This edition 2009 Omnibus Press

(A Division of Music Sales Limited, 14-15 Berners Street, London, W1T 3LJ)

ISBN: 978-0-85712-048-9

The Author hereby asserts his/her right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with Sections 77 to 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, expect by a reviewer who may quote brief passages.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of the photographs in this book, but one or two were unreachable. We would be grateful if the photographers concerned would contact us.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit Omnibus Press on the web at www.omnibuspress.com

For all your musical needs including instruments, sheet music and accessories, visit www.musicroom.com

For on-demand sheet music straight to your home printer, visit www.sheetmusicdirect.com

Contents

Prologue

Grammy Night

February 23, 2003

New York City

No one understood New York City better than the blue-eyed king of the crooners, Frank Sinatra. When Cranky Frank told the world if you can make it there, you can make it anywhere, he wasnt just riffing on a choice rhyming couplet.

In a million different ways, New York really is the centre of the universe, and no more so than in the feverish world of rocknroll. Although, truth be told, if a band can make it in New York City, well, theyve probably already made it everywhere else. Its the Everest of entertainment. If you were planning on proving just how high youd climbed, theres no better stage than Madison Square Garden, or a bigger occasion than the Grammy Awards, the annual backslapping celebration of pop music success and excess. Backstage, however, Madison Square Garden on Grammy night in 2003 wasnt that different from any other cavernous entertainment bunker. A vision in concrete, with rabbit-warren corridors leading off to mysterious corners, it could, for a moment, make you forget about the 20,000 anxious, eager fans awaiting your presence in the darkness.

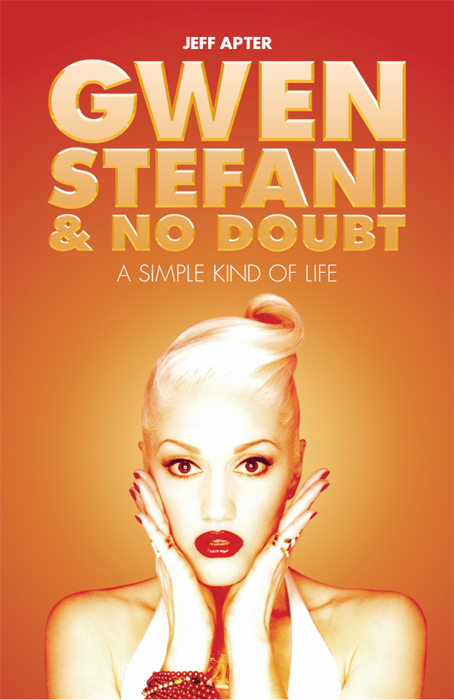

Not that No Doubt seemed to mind. Sixteen years down the line, this Orange County, California, gang of four were finally, irrefutably, comfortable in their own skins. They didnt even seem to be overly concerned that outside, during rehearsals on the main stage, R&B princess Ashanti was having technical difficulties involving a group of performing children and some kind of hydraulic mechanism, which meant that No Doubts rehearsal time had been delayed. It had taken them a long time to get here; so they were soaking up the moment.

Even though life was sweet right now, five albums and 20-odd million record sales into their long, weird musical trip, the majority of those 16 years had been hard going. For longer than they would care to recall, No Doubt had been little more than darlings of the tight-knit and undeniably parochial So-Cal ska scene. Not only had they been famously rejected by taste-making Los Angeles radio station KROQ, they had also been told that they lacked focus by one of their early A&R guys at Interscope Records, a man paid to be a true believer in this band-cum-gang. And itd be wrong to say that Interscope, the label founded by major industry player Jimmy Iovine, had always been No Doubts biggest champions. There was even a stage in the early Nineties when the band pooled their cash to release their second LP, Beacon Street Collection, out of pure frustration with the never-ending sessions for what would turn out to be their career-making LP, Tragic Kingdom. They were forced to sell Beacon Street via mail order and at gigs.

Yet for No Doubt, through adversity, came success ultimately on a scale once totally unfathomable to the ska-pop hopefuls from Anaheim. Gwen Stefanis brother Eric, the co-founder, songwriter, and chief motivator of the band, walked away from No Doubt in late 1994, opting for a career as an animator for The Simpsons. Seven years earlier, the band had suffered an even more painful loss when their original singer, John Spence, committed suicide. Around the time of Erics departure, the seven-year romance between Gwen Stefani and No Doubt bassist Tony Kanal also fell apart. Within months back in 1994 No Doubt had taken not one, but two hits to the head, the kind of internal turmoil that would kill most under-achieving bands stone dead. Yet No Doubt was no under-achieving band. Kanal and Gwen Stefani found a way to play together on-, but not off-stage, without killing each other. Gwen in her unexpected role as band lyricist discovered her split with Kanal gave her plenty of juicy subject matter for songwriting.

And so No Doubt as we know it was born.

Dont Speak, which quoted directly from intimate exchanges between Kanal and Gwen, became an anthem for millions of broken-hearted teens in 1996, while the video became an MTV staple. Somewhere in the midst of all this activity, Gwen, a self-confessed nerd and geek, transformed herself into what one critic would call Doris Day in a tank top and bondage pants, a pin-up for teens not quite prepared to embrace the raw junkie-chic of Hole shouter (and recent rocknroll widow), Courtney Love. The cult of the Gwenabees began. A star was unmistakably born.

And just 18 months after its 1995 release, Tragic Kingdom, the bands third album, redefined the term ubiquitous. As sleepers go, Rip van Winkle had nothing on Tragic Kingdom. Within a couple of years it would become that rarest of beasts: a Diamond album, which meant that it had shifted more than 10 million copies in the US. It briefly propelled this remarkably self-effacing Anaheim crew into the lofty company of such mega-selling legends as Pink Floyd and The Eagles, whose Dark Side of the Moon and Hotel California, respectively, had also gone Diamond.

Meanwhile, backstage at the Garden, several years and several million albums later, the members of No Doubt were engrossed in their own worlds. Drummer Adrian Young, the first No Doubt parent and one of the few golf junkies to sport both a Mohawk and a single-figure handicap was absorbed in his iBook, checking out images of his recently born son, Mason. (Keeping it very much in the family, Youngs wife, Nina, is No Doubts former production co-ordinator.) If there was anyone in No Doubt whod stayed relatively true to his punkish roots, it would be Young, a frenetic flurry of hands, legs and arms behind his kit, whod strip down to his boxers or less to perform.

Guitarist Tom Dumont was nearby, with a knit cap pulled down low over his eyes and sandy hair. An adopted middle child, Dumont didnt really share the same musical bent as his bandmates growing up. Rather than the interracial ska of such revered UK acts as Madness and Specials AKA, or the Eighties new wave peddled by LA station KROQ, Dumont fancied the brawny, brainy prog rock of Canadians Rush, and the cartoon riffs of Kiss. Dumont loved Kiss so much, in fact, that he bought his first electric guitar, a black Les Paul Gibson, primarily because it was the chosen axe of Kiss guitarist Ace Frehley. While No Doubt never claimed to be musos musos, Dumont was as close as the band would come to having a serious player amongst their numbers.