All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Photo credits are located on .

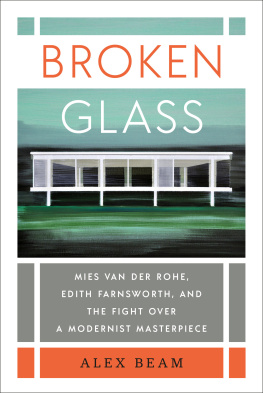

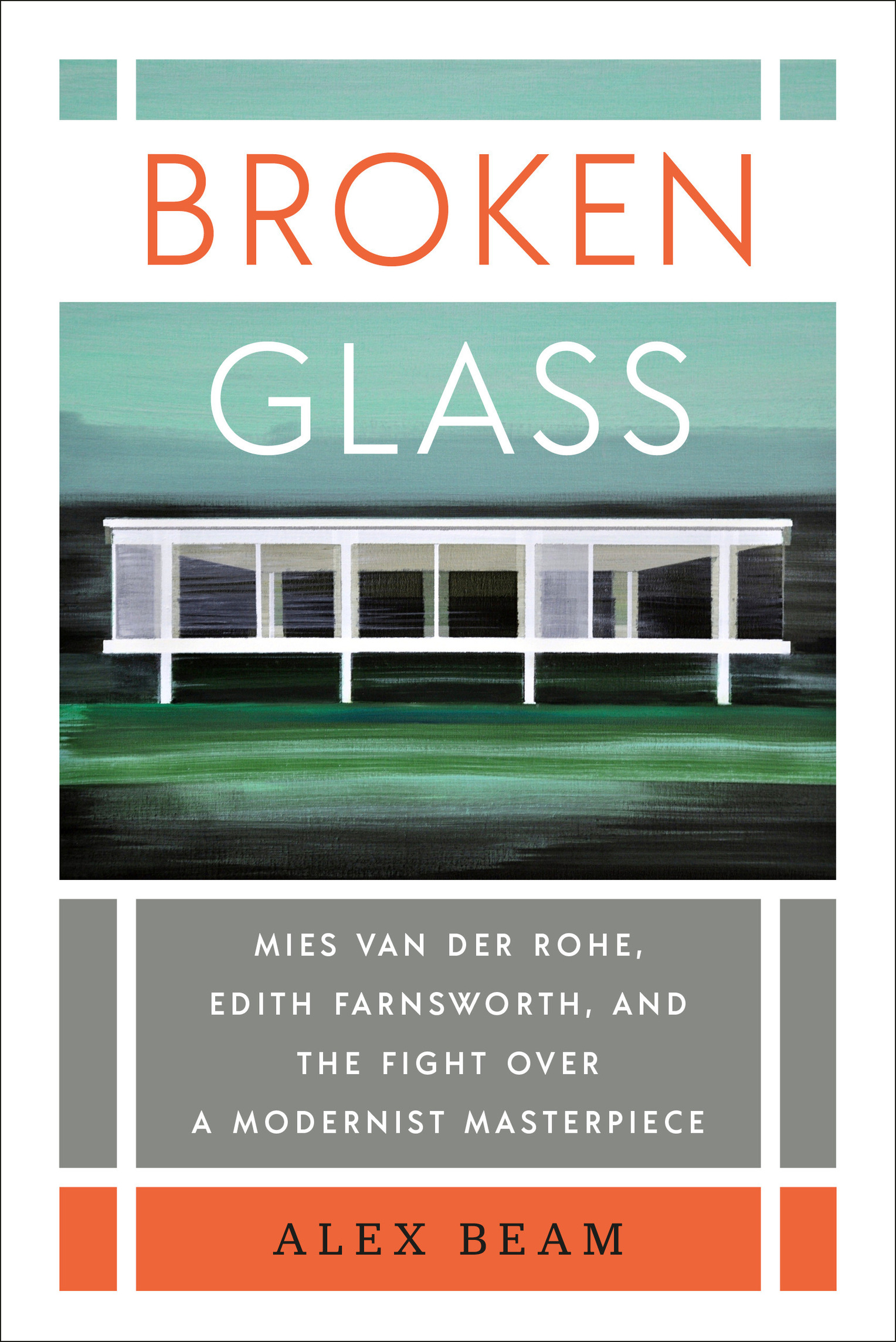

N AMES: Beam, Alex, author.

T ITLE: Broken glass: Mies van der Rohe, Edith Farnsworth, and the fight over a modernist masterpiece / Alex Beam.

D ESCRIPTION: New York: Random House, [2020] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

I DENTIFIERS: LCCN 2019022841 (print) | LCCN 2019022842 (ebook) | ISBN 9780399592713 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780399592720 (ebook)

S UBJECTS: LCSH: Farnsworth House (Plano, Ill.) | Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig, 18861969. | Farnsworth, Edith. | Architecture and societyUnited StatesHistory20th century.

C LASSIFICATION: LCC NA7238.P53 B43 2020 (print) | LCC NA7238.P53 (ebook) | DDC 720.9773/0904dc23

PROLOGUE

THIS IS MIES, DARLING.

Mies van der Rohe and Edith Farnsworth met at a small dinner party in Chicago during the winter of 1945. Gallery owner Georgia Lingafelt shared a downtown apartment in the Irving, an elegant low-rise on the North Side, with her friend Ruth Lee. Lingafelt invited three guests who lived nearby on Chicagos affluent Gold Coast: Mies, his girlfriend Lora Marx, and Dr. Farnsworth, a physician, art collector, and poetry aficionado.

While Edith slipped off her overcoat in the foyer, Lingafelt smiled graciously and introduced her to the guest of honor: This is Mies, darling.

The dinner conversation stumbled forward. Mies, who had immigrated to the United States from Germany seven years before, still hadnt mastered English. (He never would.) Farnsworth later recalled that the women chatted among ourselves around the granite form of Mies.

When Marx and the hostesses repaired to the kitchen to wash dishes, Farnsworth conversed with Mies. She knew he was a famous architect but knew nothing of his work. Recruited to revamp the architecture department of the Illinois Institute of Technology, Mies had yet to complete a building or residence in the United States.

Mies had no idea who Edith might be, but she was the kind of woman he had been attracted to before: intelligent, stylish, and not a settle downer. The unmarried Farnsworth was forty-two years old and had abandoned a promising career as a violinist to study medicine. Mies, who lived alone, had sampled domesticity, and it didnt agree with him. Hed abandoned his wife and three daughters in wartime Germany. As a married man, he was a caricature, according to a German friend. There was something about him that thrived on freedom, required exemption from convention.

Farnsworth told Mies that she had recently bought a parcel of land about an hour southwest of the city, in Plano, Illinois. It was a gorgeous meadow sloping down to the meandering Fox River. She was hoping to build a small weekend cottage there, to escape the demands of her research and clinical work as a kidney specialist at Passavant Memorial Hospital. She wanted to fill her tired, dull Sundays, as she described her off-call weekends in Chicago. She intended to spend $8,000 to $10,000, the equivalent of about $110,000 today.

I wonder if there might be some young man in your office who would be willing to design a small studio weekend-house worthy of that lovely shore, she asked.

I would love to build any kind of house for you, Mies replied. Coming from this taciturn massive stranger, as she described him later, the effect was tremendous, like a storm, a flood or other act of God.

Mies had that effect on people. Sixty years old and already feeling the effects of the arthritis that would later cripple him, he still had an oracular presence that particularly appealed to women. Mies was the epitome of old-fashioned masculinity, according to Farnsworths contemporary, the curator Katharine Kuh. His deep, slightly gravelly voice, his slow, accented speech, his elimination of small talk, and his quiet self-assurance all contributed to this image.

Several years later, Mies struggled to recapture details of that fateful conversation. He remembered discussing an unusual, nonstandard project with his prospective client. She knew that she would get a house that was not normal, Mies said. When we talked the first time about the house, at that dinner party, I told her I would not be interested in a normal house, but if it could be fine and interesting, then I would do it.

Mies and Edith would soon make architectural history. The Farnsworth House was indeed fine, it wasnt normal, and it was captivating. The house has found its place in the architectural canon, in the slide deck of almost every serious introductory architecture lecture in the world. Architect/critic David Holowka has called the Farnsworth the urtext of modern residential architecture: Ernest Hemingway famously wrote, All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn. It might as accurately be said that all modern houses come from Mies van der Rohes Farnsworth House.

Holowka later elaborated: Icons like Le Corbusiers Villa Savoye are equally famous, but it was Miess unerring grasp of the irreducible and universal that make his Farnsworth House concept primary and durable, he said.

It plugs into ideas as old as the human impulse toward the primitive hut and as current as [anti-stuff crusader] Marie Kondo. Its both groundbreaking and rooted in the fundamental psychological problem of the house: how to resolve our need for shelter with the contradictory human desire for spaceto be outside in nature, our evolutionary place where in many ways we still feel most at home.

The critic Paul Goldberger once remarked that there seems at first to be almost nothing to [the Farnsworth House]a house so light it might float away. The phrase nothing to it invokes Miess famous dictum of beinahe nichts, almost nothing, his idea that architecture, at its best, should be almost invisible. The Farnsworth House left other architects little to do except to try to make even more perfect that which was already perfected, according to iconoclastic British architectural critic Reyner Banham.