Introduction

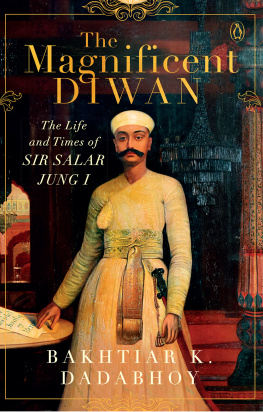

M ir Turab Ali Khan Bahadur Sir Salar Jung Shuja-ud-Daula Mukhtar-ul-Mulk, G.C.S.I., D.C.L., better known as Sir Salar Jung I, diwan (prime minister) of the nizams dominions from 1853 to 1883, was arguably the foremost statesman and diplomat that India produced since the establishment of the British supremacy. In his lifetime, his fame transcended the limits of not only Hyderabad, but also of India, but today there are no crossroads or avenues named in memory of the founder of modern Hyderabad. This lack of civic memorialization can hardly be said to be mitigated by the fact that, ironically, the name Salar Jung is remembered in connection with a museum in Hyderabad which houses the collection of art and artefacts of his grandson, Mir Yousuf Ali Khan Salar Jung III.

Details about Salar Jungs early life are few, and provide little material to trace the development and formation of a character which, for a generation, exercised a commanding influence over the destiny of Hyderabad. His life and character form an inseparable part of the history which he himself enacted since early manhood. A man with a broad and enlightened mind and a strong will, Salar Jung applied his rare energies to the improvement of Hyderabad and the amelioration of the condition of its people. His long and illustrious career was also distinguished by his efforts to promote friendly relations between the nizam and the British government. The unexampled prosperity of Hyderabad since it fell under the administration of Salar Jung was a subject of much comment.

An Arab by descent, two of his family before him had filled the post of diwan, but he was by far the most distinguished representative of his family, becoming diwan when he was only twenty-four on the death of his uncle, Siraj-ul-Mulk. As a boy, he was taught English, and was closely associated with the family of the British resident in his formative years. His opinion of the British as a just and honourable people must have been formed at this time, and it was something he believed in all his life, only to be greatly disillusioned towards the end.

Salar Jung had an enviable command of English and an intimate acquaintance with English ideas and with Western statesmanship. Though he was very comfortable in European societyoften referred to as the Anglophile minister of Hyderabad, and contemptuously called firanghi bachcha (foreign boy) by the nizamhe never ceased to be Indian. He did much to bring together the European and the Oriental in friendly social intercourse. Salar Jungs refined manners, enlightened views and generous hospitality made him a great favourite with Englishmen.

His palace was also furnished in English styleperhaps with more ostentation than taste, but he also stubbornly fought to preserve the old Mughlai ways in social intercourse, and to preserve old customs, mistakenly believing that changes and reforms in the administrative and political spheres could be kept separate from the religious and social. At the Delhi durbar in 1877, he was the only Indian who made a speech in English. But though he adopted much of Western culture, he was never a denationalized Indian, remaining faithful to the traditions of his creed and country.

When Salar Jung became diwan, the economy and the finances of the government were in a shambles. There was discord among the nobles, and the authority of the nizam was little more than a farce. The roads were patrolled by bands of robbers, and each noblemans palace was a nest of brigands. And with the Governor General, Lord Dalhousie, just waiting to annex as much territory as he could, Salar Jung, when he assumed office, was faced with dangers both from within and without. Many thought that the days of Hyderabad as an independent principality were numbered. It was Salar Jungs great achievement that he disappointed these expectations, and showed in the most remarkable manner, that in his person the hour had indeed produced the man.

Salar Jung first turned his attention to the restoration of law and order and to rescue Hyderabad from its embarrassment. At that time, there were a large number of Arab mercenaries employed in the nizams army. They were amenable only to their own chiefs, and subject only to the laws and customs of their own country. They were outside the pale of the justice system (or whatever passed for it) of Hyderabad. The laxity of the desert soon became the license of the town, and the Arabs soon terrorized the very people they were supposed to protect. Salar Jung, by a combination of coercion and concession, succeeded in taming the Arabs before devoting his energies to the other evils that clamoured for his attention.

He had inherited a Hyderabad which was almost a wilderness, one in which anarchy and lawlessness reigned without a check. His uncles legacy included an empty treasury, heavy debts, large arrears to the city troops and no credit. The credit of the government was so low that his uncle could have borrowed Rs 10,000 from bankers, if at all, with great difficulty. Money could not be obtained from sahukars, except under the guarantee of the military chiefs and that too at extortionate rates. Salar Jung, by his personal character, restored credit to the government such as it had never possessed before.