Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

ALSO BY ELISABETH SBRINK

1947: Where Now Begins

Made in Sweden

Originally published in Swedish as Och i Wienerwald str trden kvar in 2011 by Natur & Kultur, Stockholm

Copyright Elisabeth sbrink and Natur & Kultur 2011

English translation copyright Other Press 2020

Published by arrangement with Partners in Stories Stockholm AB

The cost of this translation was supported by a grant from the Swedish Arts Council.

The preface was written by the author in English for this edition.

Poetry excerpt on from The Tales of Ensign Stl by Johan Ludvig Runeberg, in Delphi Collected Works by Johan Ludvig Runeberg (Illustrated), Delphi Poets Series Book 56, translated by Clement B. Shaw.

Copyright Delphi Classics, 2015

Production editor: Yvonne E. Crdenas

Text designer: Jennifer Daddio / Bookmark Design & Media Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 267 Fifth Avenue, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: sbrink, Elisabeth, author. | Vogel, Saskia, translator.

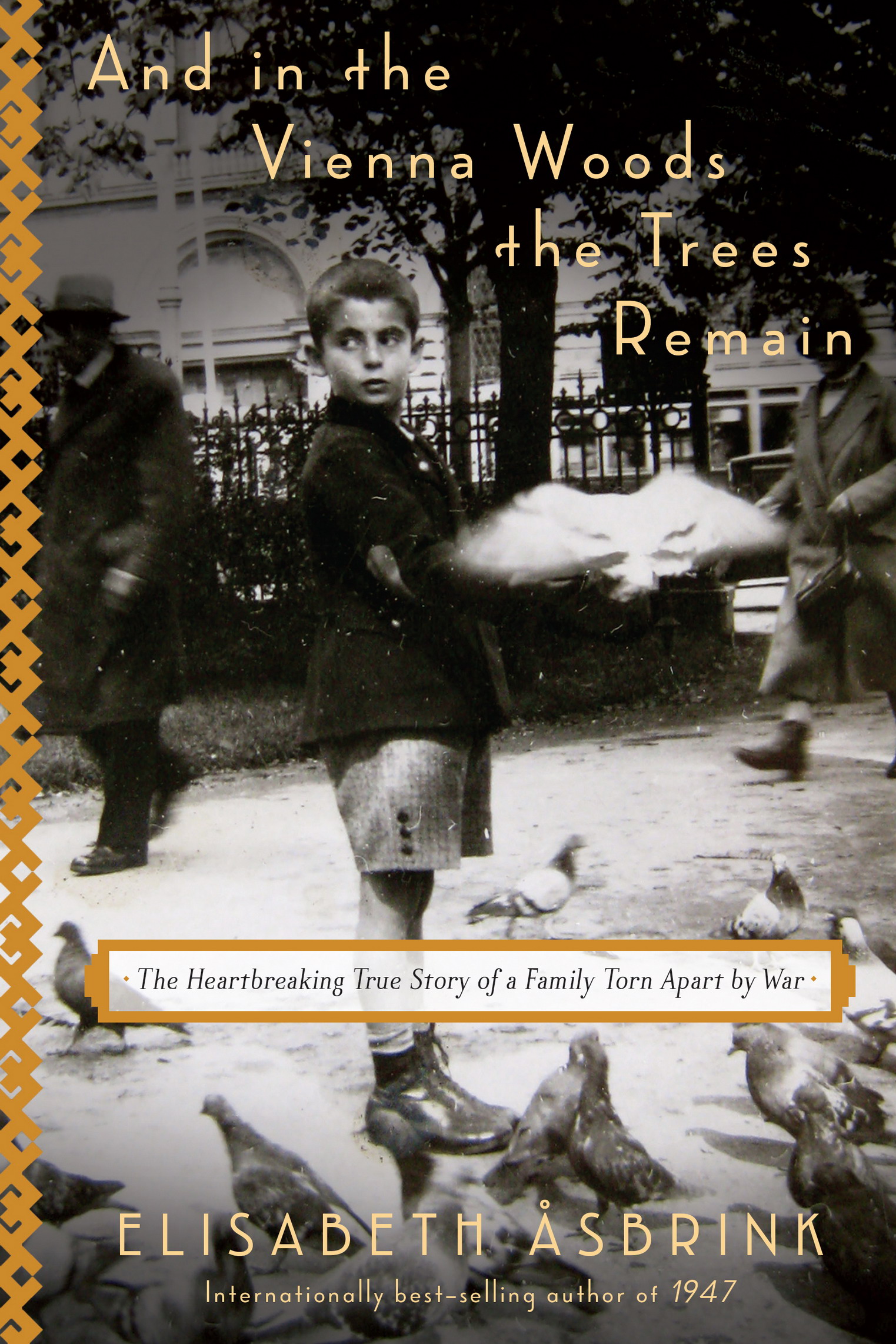

Title: And in the Vienna woods the trees remain : the heartbreaking true story of a family torn apart by war / Elisabeth sbrink; translated by Saskia Vogel.

Other titles: Och i Wienerwald str trden kvar. English

Description: New York : Other Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019275 | ISBN 9781590519172 (hardback) |

ISBN 9781590519189 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Ullmann, Otto, 1925-2005. | Jewish refugeesSwedenBiography. |

BISAC: HISTORY / Modern / 20th Century. | HISTORY / Holocaust. |

HISTORY / Europe / Scandinavia.

Classification: LCC DS135.S89 U45313 2020 | DDC 940.53/18092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019275

Ebook ISBN9781590519189

v5.4

a

Preface

This was a book I had no intention of writing. On the contrary, the story of Otto Ullmann, a Jewish refugee child who was sent to Sweden to escape Nazi persecution, came to me as an offer and I turned it down.

Eva Ullmanthe daughter of Ottoasked to speak with me. She brought with her a trauma tied tight with string and asked for my help to unknot it. This is what she told me:

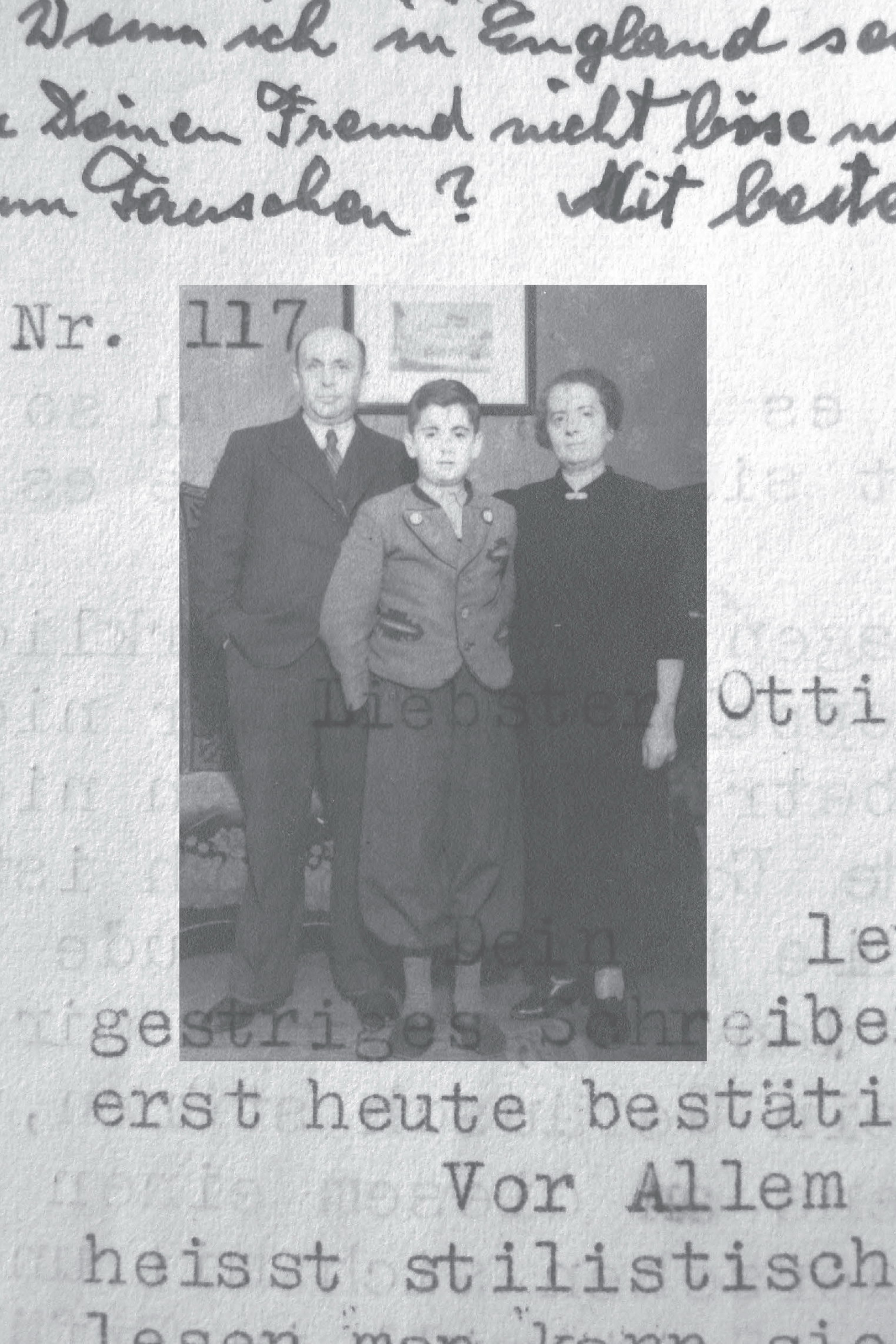

Her father was born and raised in a middle-class family in Vienna, a cherished and strong-willed child who loved music and soccer. When Hitler annexed Austria in March 1938, he was twelve years old. Like all Austrian Jews, the Ullmann family was heavily affected from one day to the next, and the persecution had just begun. Ottos parents decided to save their only child first, and managed to get him to Sweden in early spring 1939. The plan was to join him later, but until that became possible, they would write him a letter a day. Otto spent a year in an orphanage in the south of Sweden. Then, at the age of fourteen, he had to support himself and became a farmhand. Meanwhile, the letters from Ottos parents in Vienna continued to come, until the day they came no more.

In early 1944 Otto Ullmann applied for a job at the Kamprad estate in Smland and became best friends with the landowners son, Ingvar. Later, when Ingvar Kamprad decided to create the furniture company IKEA, Otto was his right-hand man and sidekick for a decade.

Would I like to write something about this, Ottos daughter now wondered? Then, ironically, she handed over an IKEA storage box that for years had been at the back of one of her closets, never opened but never forgotten. There they were, more than five hundred letters from Ottos parents, with Hitlers profile on the stamps.

When Otto Ullmann died, Eva had reluctantly taken care of the letters but never read them. As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, she grew up learning that there were some areas not to be tread on, some words better left unsaid, and some questions never to be asked. And she understood that at the very epicenter of silence were her father and his survival. So the letters were placed in the IKEA box, lid on, until she got the idea of offering them to me.

I said thank you, but no thank you. I couldnt. I wouldnt. Impossible. Im sorry. The letters were of course written in German, a language of which I had little knowledge, but that wasnt the main reason. I simply couldnt stand the idea of writing about the Holocaust. The unbreakable silence within the Ullmann family was all too recognizable, it existed also within my family. And so we said goodbye.

But then, night after night, before going to sleep, I found myself imagining the letters going from Vienna to the south of Sweden, one a day from parent to child. The image just wouldnt leave me alone.

The result is this book, a story about a boy and his parents. And within the story is another, about one of the worlds most famous men, the founder of IKEA, who not only was a member of the Swedish hard-core Nazi party but at the same time loved his best friend, the Jewish refugee Otto Ullmann. All in all, it turned out to be an account of Sweden before the country became a good one.

Ingvar Kamprad let me interview him (the result is in the book). But when I found the files from 1943 in the Swedish Secret Police Archive, stating he was member 4014 in Swedish Socialist Unity (Svensk Socialistisk Samling, or SSS), the Swedish Nazi party at the time, he declined any further contact.

And the letters? They are still in that IKEA box, waiting for transfer to an archive where they will be made available to researchers. Im not sure I could fulfill Eva Ullmans wishes, that through words the trauma might be unknotted. But the process of research and writing managed to dissolve some of the silence and the lack of knowledge. It also defined the connection between Eva and myselfand so many others: the experience of carrying the weight of a familys pain.

Contents

A child stood outside a building in a large city. It is a time gone by. The river splitting the city was like a wound; seven bridges kept it stitched together, binding the hills to the plains, greenery to exhaust fumes. Budapest.

The boy was playing on a small square just outside his front door. His father was at work, his mother was at home in their apartment a few floors up. He had no siblings, and his friends must have been elsewhere. He was five years old, and perhaps he liked his solitude.

A passerby paused to look at him, an adult who then yelled at him in such a way that he immediately stopped playing. That word, hed never heard it before, but the expletives, the tone, the malice were unmistakable. As was the gaze: directed right at him.