FROM AS:

To my father

FROM JB:

To the good Samaritan

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

IT TURNS OUT that the white-tunnel stuff is overrated.

Scientists in the Netherlands recently conducted a study of people whod been resuscitated from clinical deathmeaning that their hearts had stopped beatingand only 18 percent reported any sort of mystical experience during the moments they were deceased. On June 30, 2007, the day when I died, I joined the majority. I wasnt transported through a blazing white tunnel, my soul didnt drift out of my body, and I didnt look down at myself sprawled on the thick grass outside the Lance Armstrong Sports and Fitness Center on the campus of Nike headquarters near Beaverton, Oregon. My death, in fact, was pretty straightforward.

One moment I was walking along with my runners, talking about where to go for lunch, and the next I was in a hospital room, clutching a chain of rosary beads. Between those two moments I knew only blackness and oblivion. Thats sort of surprising, actually. Given my extensive near-death rsum and familiarity with miracles, youd think I wouldve landed among the 18 percent of the subjects of the study who, at the moment of their seeming end, knew a sense of serene oneness or witnessed their entire lives flashing in front of them.

Maybe I failed to see the white light because I was dead a whole lot longer than the people in that study. Most of the bodys organs can survive the loss of circulating blood for up to 30 minutes, and detached limbs can be successfully reattached for up to 6 hours following the dismembering injury. After more than 5 minutes without a pulse, however, full recovery of the brain becomes extremely unlikely. Three hundred thousand Americans die every year from cardiac events, but strictly speaking, they dont perish from blocked arteries or a stilled heart. After a very few minutes10 at the mostwithout a fresh supply of blood, your brain starves of oxygen, and thats what really kills you.

I was clinically dead for 14 minutes.

Fourteen minutes is a long time. Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address in much less than 14 minutes. In my competitive prime, I could easily run 3 miles in 14 minutes. You can watch half of a TV sitcom episode, commercials included, in 14 minutes. None of the doctors who treated me, and none of the experts Ive consulted since the day I collapsed, have ever heard of anybody being gone for that long and coming back to full health. By all rights, I shouldve been DOA at the emergency room of Providence St. Vincent Medical Center. At best (or at worst, depending on your viewpoint), I might have hung on for a few days or weeks in a brain-dead coma until Molly, my wife, made the agonizing decision to unhook me from the respirator. If I were really lucky (or, again, if my family was especially cursed), perhaps Id have survived as a brain-damaged shell of a human being. But instead, on the day after my clinical death, I was chatting to visitors in my hospital room, and 9 days later, with my body whole and my faculties intact, I was back coaching at the same spot where Id collapsed.

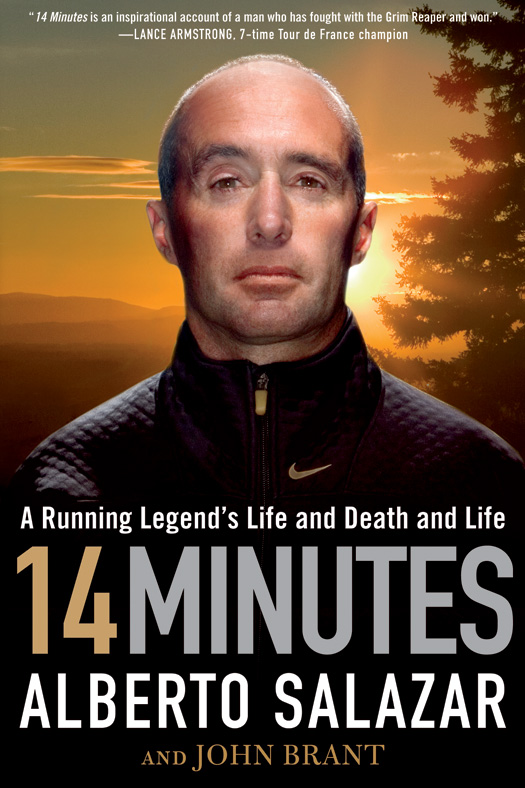

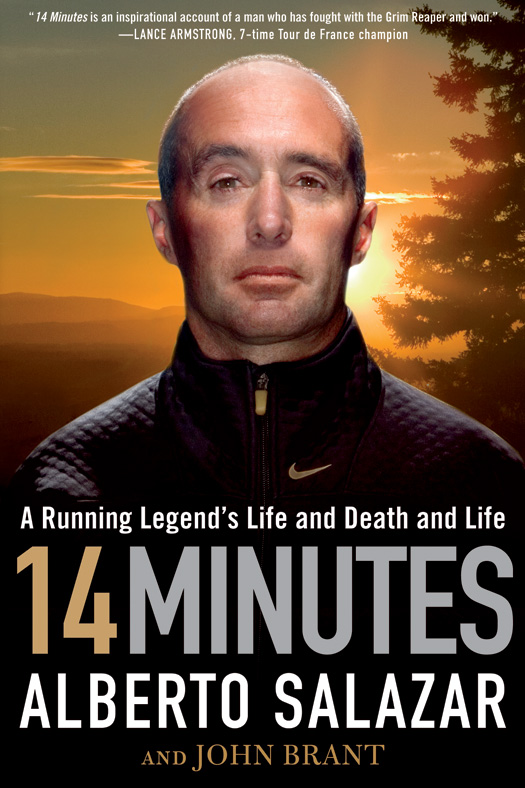

In October 1981, I set a world record (or WR, in runners parlance) at the New York City Marathon, covering the 26.2-mile distance in 2 hours, 8 minutes, and 13 seconds. That performance sealed my standing as the greatest distance runner of my era. I lived a life of extreme athletic excess, as far gone, in my way, as a drug addict or alcoholic. I was famousor many would say, notoriousfor my obsession to outwork any rival and for my absolute refusal to lose. I would later pay a harrowing, decade-long penance for that excess, but at the time, in the late 70s and early 80s, the height of the first running boom, my obsessiveness put me on top of the world. My photo appeared on the cover of national magazines, I shook hands with President Ronald Reagan at a ceremony at the White House, and Nike named an apparel line after me. Now, 25 years later, here I was racking up a second, albeit unofficial, WR: 14 minutes.

We were in a loose, celebratory mood on that summer Saturday morning in 2007 at the Nike campus. My Nike Oregon Project team had just returned from the US national track-and-field championships in Indianapolis, where three of our athletes, Kara Goucher, Adam Goucher (Karas husband), and Galen Rupp, had all placed in the top three in their respective races and thus earned spots at the world championships in Japan later that summer. In a non-Olympic year, this was the professional distance-running equivalent of making it to the Super Bowl, and we were elated.

It had been 6 years since I started coaching the Nike-sponsored Oregon Project. With the full backing of the companys founder, Phil Knight, and then-president Tom Clarke, I was on a mission to develop an American-bred champion of one of the worlds major marathons. Amazingly, only one male American distance runner had won one of the toptier races since I won New York in 1982 (in 1983, Greg Meyer won the Boston Marathon), and Philalong with the entire US sports establishmentwas hungry for a homegrown hero to challenge the dominance of the Kenyans and Ethiopians. No one knew better than I did what it took to reach this level, and no one knew better the hazards: the various physical, psychological, and spiritual disasters that a runner potentially encountered as he or she approached the edge separating supremely difficult training from self-immolating excess. My job was to drive a handful of elite young American runners to that edge but keep them from tipping over.

On that morning, it seemed like I had struck the winning balance. We had successfully endured the crucible of the nationals. The pressure was off, and I was giving my runners some semidowntime. Kara and Adam werent running at all for a few days, and Galen was scheduled for a relatively easy workout consisting of a moderately paced 5-mile run followed by a round of quickness- and strength-training drills that hed go through with Josh Rohatinsky, a promising young runner from Brigham Young University with whom Id just started to work. Jared, Joshs younger brother, was in town visiting. Jared, Josh, Galen, and I were walking from the parking lot toward the Lance Armstrong Center.

It was a soft, beautiful summer morning, the kind that only seems to occur in Oregons Willamette Valley. Warm sunshine was burning off the light morning overcast, and the air was so clear that the world seemed to glisten. Days like this are our payoff for the 8 months of gloom. People complain about the infamous Oregon rain, but in general it doesnt bother me that much. A persistent, mild drizzle seems a small inconvenience compared to the blasting winter winds that I grew up with in Connecticut and Massachusetts.

We were headed for the central green to do the plyometric drills, and we were talking about where to go for lunch. I was 48 years old, on top of my profession, and blessed with a happy, healthy family. I was cutting across the gleaming campus of a mighty multinational corporation whose resources lay at my disposal. Nike had even named one of the office buildings after me; you could see the roof of the Alberto Salazar Building from where we were walking. I was with people I cared about, doing the work that I loved. Everything seemed about perfect, and yet I was moments away from dying.

Next page