PREFACE

I was unprepared for the derision that came my way soon after I began researching this book. Critics assumed that nothing new could be found to justify publication of yet another volume on the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. I always replied that five hundred artists painting the same landscape would come up with five hundred different canvases, none of which could be stamped as definitive.

Nine years later my tale is told and They Have Killed Papa Dead! bulges with new finds. It is unlikely they could have been uncovered by anyone living beyond my commuting distance, twenty miles from the Library of Congress and the National Archives. Proximity to these institutions gave me the luxury of searching for primary source material for weeks on end, year after year.

From the outset I worked on the assumption that nineteenth-century Washingtonians would more likely have confided in their daily chronicles and extended families than in officialdom or anyone else. And so I went hunting for private letters, diaries, and journals, the authentic voices of contemporaneous observers. There was no doubt they would provide texture, insight, and color for the era.

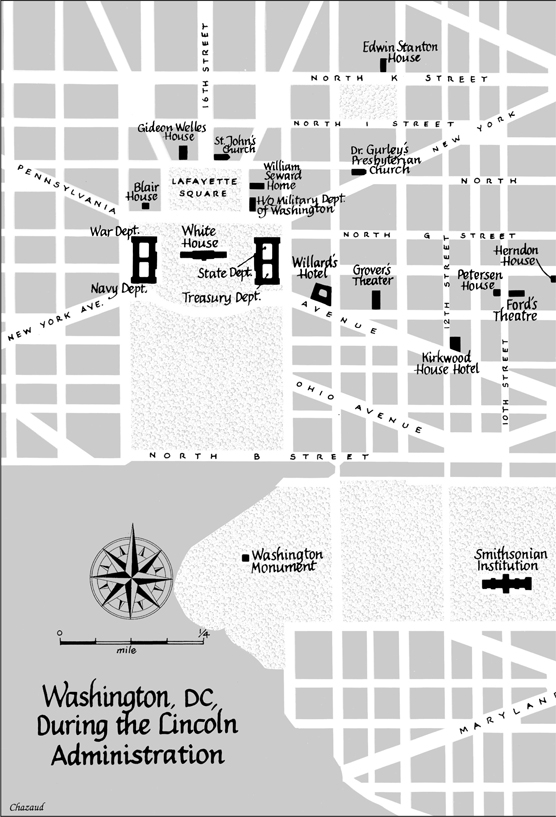

I never expected such a sequence of surprises. Many voices began to speak, as if competing to break confidences and disclose impressions. Very early into my research I could not stifle a whistle on finding a letter from Benjamin Brown French, commissioner of public buildings, describing how he forcibly restrained John Wilkes Booth from doing possible harm to President Lincoln in the rotunda of the US Capitol during second inaugural ceremonies, six weeks before the assassination. When I found a later letter by French, his yearning for vengeance was as fresh as the day he wrote of the quartet of conspirators put to death for Lincoln's murder: I could have jumped upon the shoulders of each as they hung, after the ancient manner of rendering death certain. With oversight of White House expenditures, French probably knew Mary Todd Lincoln better than any other public official, which gave credence to a confidence he shared in private correspondence after the assassination, of the president's wife purchasing about one thousand dollars worth of mourning goods a month before the murder. What do you suppose possessed her to do it! Please keep that fact in your own house.

As testimony in the everlasting trial of the conspirators came to a close, one of the rigidly stern military judges figuratively leapt out of the courtroom to write his wife, I feel like a boy out of school. In another letter to a spouse, the irritable architect of the Capitol, Thomas Walter, confessed to being unmoved by the obsequies that had overcome other Washingtonians, regretting instead that Lincoln's lying in state stops work another day, which is wholly useless. One diarist fortunate to enter the White House to view Lincoln's coffin (tens of thousands were turned away at the gates) came away with the lasting impression of its being studded with great numbers of silver nails. Another chronicler, standing within twenty feet of the president during the second inaugural address, recalled Lincoln's loud, rather shrill, distinct, far-reaching voice.

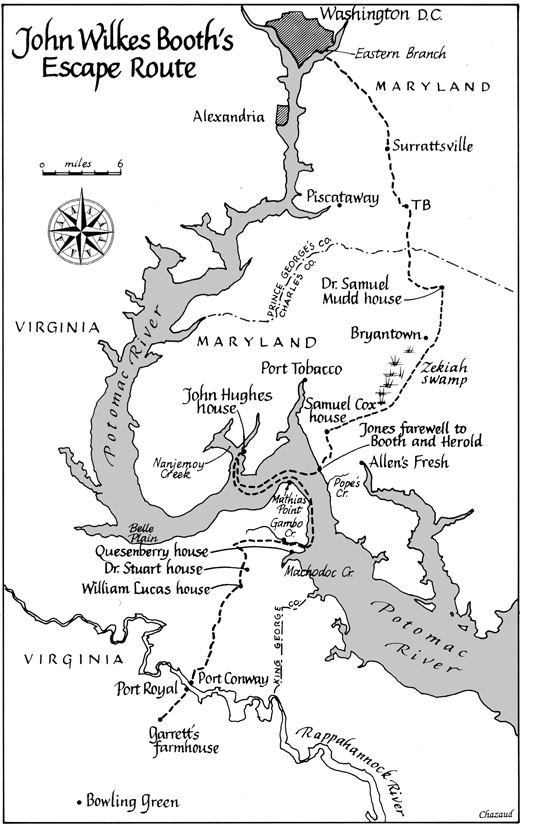

Tracking the escape of co-conspirator John Surratt to Rome, at a time when the pope's temporal authority was crumbling in the face of armed opponents intent on unifying the country, led me to correspondence between the US Minister to the Papal States and the State Department in Washington. In one extraordinary letter, the American diplomat reported that several officials in the papal government had confided to him that if the Pope felt to abandon Rome he might seek refuge in the United States. The decline of papal political power and the Vatican's need for allies may well have influenced the pope to surrender Surratt into the custody of American officials.

As if to vindicate years in quest of new material, I unearthed an electrifying letter in the National Archives from one of the convicted conspirators, Samuel Arnold, to his nemesis, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. When I found it just months before finishing this book, I was probably the only person to have read it since it was filed into virtual oblivion 143 years earlier. In his distinctively neat, right-sloping script, Arnold had applied for a job three months after enthusiastically signing on to John Wilkes Booth's madcap scheme to kidnap the president. Even Arnold overlooked this letter in the trial that took place six months after he wrote it, for he never mentioned it to solicit belief that he had wavered in support of the conspiracy.

My luckiest find came in a sprawling warehouse filled with antiques from a consortium of dealers in the quaint Pennsylvania town of New Oxford, ten miles east of Gettysburg. I do not recall why I suddenly looked up after exploring rooms full of aging and rusty exhibits, but the framed page of a broadsheet newspaper caught my eye and I had to buzz the reception desk for help in hauling it down. The glass-enclosed front page had columns of print about a credible plot to abduct President Lincoln and carry him off to the Confederate capital of Richmond. Until that moment I had dismissed a crucial prosecution witness, Louis Weichmann, as a perjurer or at best forgetful, for having testified, I remember seeing in the New York Tribune of March 19, the capture of President Lincoln fully discussed I assumed he meant 1865, the year of the assassination, and had scanned many editions of the Tribune on that and surrounding dates, looking for the story, but had always drawn a blank. Only now did I know why it had eluded me. The framed broadsheet happened to be the same edition Weichmann had referred to in his testimony the New York