First published by Pitch Publishing, 2017

Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

Mike Procter; Lungani, Zama, 2017

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

A CIP catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

Print ISBN 9781785312168

eBook ISBN 9781785313417

--

Ebook Conversion by www.eBookPartnership.com

Contents

Acknowledgements

D ECIDING TO write a book is no easy thing, and it certainly requires a team effort. I am hugely indebted to Paul and Jane Camillin, of Pitch Publishing, for agreeing to go ahead with the book, and for being patient with all the late changes and updates. I owe Lungani Zama, my co-writer, a huge thanks, for his hours and hours of dedication and transcribing, and countless drives from Maritzburg to Durban North, as we put everything together. To Mark Nicholas, a friend who agreed on writing a foreword without a moments hesitation, my sincere thanks.

And finally, to all those who helped put this entire project together, sourcing pictures and stats from the old days, and making sense of it all. Without all of your help, none of this would have been possible.

Foreword by Mark Nicholas

T HERE IS a great sadness in South African cricket and it filters through its past. Fine cricketers, interspersed with truly great ones, are not recognised by the body that runs the modern game. With a vengeful eye, Cricket South Africa refuse to acknowledge men such as Aubrey Faulkner, Dudley Nourse, Johnny Waite, Hugh Tayfield, Graeme Pollock, Barry Richards and Mike Procter, all of whom have been denied a cap number, and refused any visible legacy. This is like saying to a young German that the two wars did not happen, or arguing that there was no America before the abolition of slavery; no Australia before Indigenous Australians had a vote.

History is fact. What is done is done. Apartheid was no fault of the cricketers: indeed, some of those cricketers paid a high price for the policies of the government of the time. But they were not of the government of the time themselves.

Cricket South Africas position is not just unfair, its daft. History offers the chance for both reflection and inspiration. Present players need to know about past players so that their place in the order of things is understood and valued. At the moment, the official line on South African cricket is that it started in 1991, when re-admitted to the ICC after 21 years of global isolation. But it didnt, it started in 1889 with a Test against England and, more than 400 Tests later, it is still going strong.

Procter is one who has suffered from this humiliation. He never grumbles, saying simply What can you do? Of course, deep down it hurts for there is no more of a cricketing man, and a South African one at that. But he cracks on forever Proccie, whose sanity remains by virtue of friends made the world over, a glass of something cold and shared memories of a game so loved.

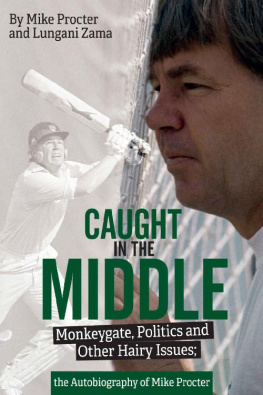

Think of the Procter CV: South Africa, Natal, Western Province, Rhodesia and Gloucestershire; Rest of the World, World Series Cricket and captain of the South African XI in the first years of the rebel tours; coach or director of cricket at international, provincial and county levels; international match referee; commentator for four networks worldwide; chairman of the national selection panel And I never lost a match at Lords! he proudly says.

He scored six consecutive hundreds in the Currie Cup, bowled the speed of light when the mood took him, swung the ball a mile, ripped his off-breaks and held most catches that came his way. He played the game in a buccaneering style, entertaining crowds and terrifying opponents. When the day was done, foe became friend and the night was young. Only a few have carried this off. Legend has it that Keith Miller played with the gods in sunlight and after dark, Sir Garry Sobers too. Another cricketing knight, Sir Ian Botham was of similar stock. Well, put Proc on the list too and if you think that an exaggeration, ask anyone around at the time.

There is no choosing the greatest all-rounder, frankly its a mugs game. Those who saw him say its Sobers, end of story. Figures tell us Jacques Kallis is top dog. Tony Greigs record has him surprisingly near the top of the charts. Perhaps only Imran Khan truly warranted a place with both bat and ball for the most part of his career but its impossible to know what any of these formidable cricketers might have achieved in one discipline without the other. Is it more, or less? Could Kapil Dev or Botham have batted with such abandon had they not bowled with such success? Do the wickets taken by Richard Hadlee and Shaun Pollock do enough to carry their erratic batting? Shall we include the stumpers Alan Knott and Adam Gilchrist in the debate? And so on.

Perhaps Botham single-handedly won more matches than any other. Maybe Proc would have matched him because his game adapted to so many different surfaces and conditions. The point about Proccie is that he excelled at every turn. He was a hero, of mine and millions of others. He was inspiration and is often reflection. His legacy is too important to be ignored.

Now he brings us up to date with a book, and what a story there is to tell. A man at the centre of so much and in the middle of so much more. During his time with various administrations, he has been both well supported and hung out to dry. The role of match referee stretched him fully and, at times, went beyond his simple truths such is the occasionally underhand nature of the modern game. The whole point about Proc is the simple truths, alongside the glorious talents. Id have paid to watch him play, indeed I did. I impersonated his quirky action, made to cream fully-pitched balls over mid-off and extra cover and even copied his style of speech. And now Ill read the book. Onwards Michael John, and bravo!

Mark Nicholas

London, March 2017

Mike Procter and Me

An introduction by John Saunders, the man Mike Procter calls the best coach I ever had.

I WAS 15 and small for my age. For several years I had had but one ambition: to play cricket for South Africa. I saw myself following in the tradition of the legendary Balaskas, the leg-spin googly bowler who a year before I had been born had bowled South Africa to their first ever victory on English soil. Xenophon Balaskas. A name redolent with magic and mystery. A name to conjure with. At Hilton College I spent every available free moment bowling in the nets. In lessons I was seldom without a cricket ball, holding it, feeling it, spinning it in my fingers. At night I would dream of leg spin bowling. My ambition to play for South Africa was shared by my closest friend, Howard an off-spin bowler. I had changed from off-spin to leg-spin bowling three years before, and could bowl a sharply turning leg break, two googlies (one disguised) and a top spinner. All I lacked was regular match practice and a modicum of control.