EVAS STORY

A survivors tale by the step-sister of Anne Frank

Eva Schloss

with

Evelyn Julia Kent

Copyright

Eva Schloss and Evelyn Julia Kent, 1988, 2012

Eva Schloss and Evelyn Julia Kent have asserted their rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the authors of this work.

Published by Eva Schloss

First published and printed in 1988

First published in eBook format in 2012

eISBN: 978-1-908886-63-7

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

Ebook Conversion by www.ebookpartnership.com

Authors note: This is a true story. As it is told from memory, some of the incidental detail may not always be quite accurate.

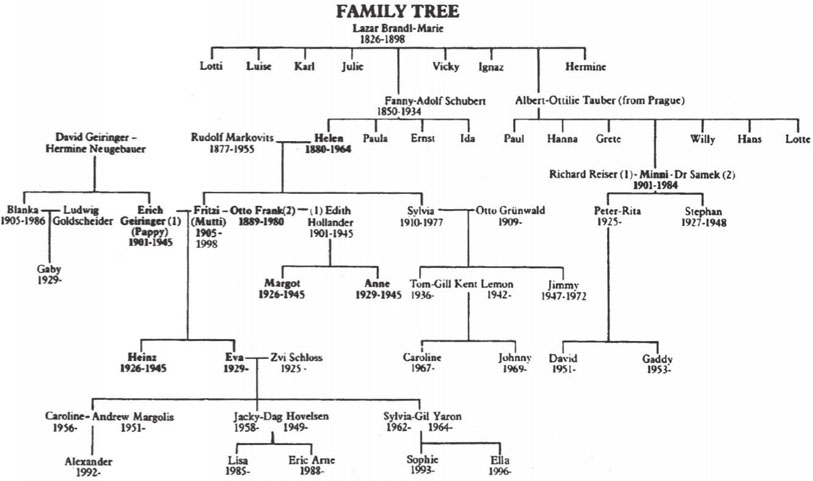

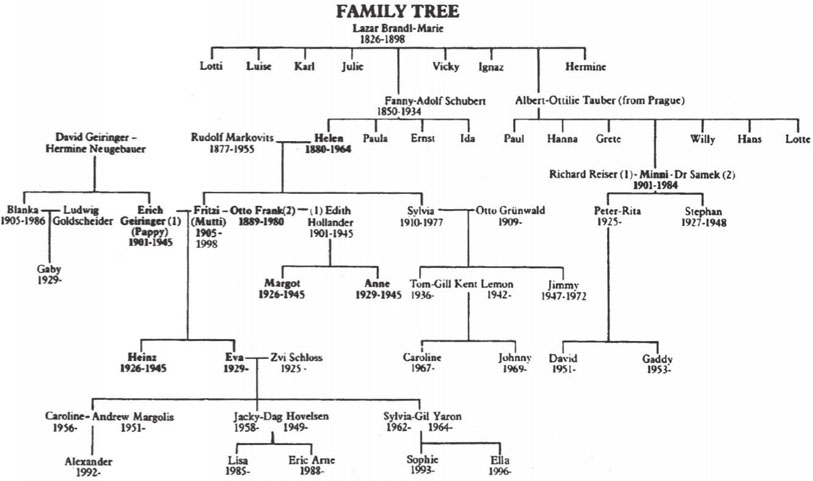

This edition is dedicated to my beloved mother Fritzi Frank (1905-1998) whose love, strength and example gave me back the confidence to lead a full life.

also

To my daughters, Caroline, Jacky and Sylvia and to my father, Erich, and my brother, Heinz, whom they never knew, with the hope that this book will bring them closer

In every ghetto, in every deportation train, in every labour camp, even in the death camps, the will to resist was strong and took many forms; fighting with those few weapons that could be found, fighting with sticks and knives, individual acts of defiance and protest, the courage of obtaining food under the threat of death, the nobility of refusing to allow the Germans their final wish to gloat over panic and despair. Even passivity was a form of resistance. Not to act, Emanuel Ringelblum wrote in the aftermath of one particularly savage reprisal, not to lift a hand against the Germans, has become the quiet passive heroism of the common Jew. To die with dignity was a form of resistance. To resist the dehumanizing, brutalizing force of evil, to refuse to be abased to the level of animals, to live through the torment, to outlive the tormentors, these too were resistance. Merely to give witness by ones own testimony was, in the end, to contribute to a moral victory. Simply to survive was a victory of the human spirit.

- Martin Gilbert,

The Holocaust: A Jewish Tragedy (Collins, 1986)

Contents

Acknowledgements

We could not have written this book without the interest and encouragement of many relatives and friends. However, we have to give special thanks to Zvi Schloss for his patient support and helpful advice; to Michael Davies for his erudite research into the chronology of the events of World War II against which the story is set; to Alistair McGechie for his able and sympathetic editing; to Pat Healy for her faith that this book would be published.

We owe much to Frank Entwistle whose constructive suggestions and wise counselling smoothed our way.

And finally to Fritzi Frank our love and grateful thanks for the copious notes and reminders that she gave without reservation.

Preface

This book started about three years ago. My husband and I were having coffee with our good friends Anita and Barry. Anita, who came to England as a child refugee in the 1930s, mentioned that her husband, who was ten years old when the war ended, did not really know anything about what had happened to me during the Holocaust.

After a few moments of hesitation, I slowly started to recount some of my experiences. Their questions were so keen, their interest so deep and yet their knowledge of those times appeared so small, that I found myself going into details, some of which I had not revealed to anyone before and had, in fact, suppressed for many years.

At the end of the evening we were all in tears and almost speechless with emotion. My friends were shocked at the thought of how remote most people now are from those events.

They and my husband urged me to write my story. This thought pursued me in the weeks that followed. It gave rise to others: I let my life pass in front of me. In spite of what had happened to me during the war I have no feelings of bitterness or hate, but on the other hand I do not believe in the goodness of man.

My posthumous step-sister, Anne Frank, wrote in her Diary: I still believe that deep down human beings are good at heart. I cannot help remembering that she wrote this before she experienced Auschwitz and Belsen.

Throughout the terrible years I had felt that I was being protected by an all-powerful being, but that source of assurance had begun to give way to some troubling questions. Why had I been spared and not millions of others, including my brother and father? Was the world improving as a result of its experience of mass annihilation? Was it not necessary to tell that story again and again and to look at it from every angle? How much time was left for the handful of survivors, before their unimaginable memories, which only they could bring to life, would be forgotten? Did not I and the other survivors owe a duty to the millions of victims to make it less likely that their deaths had been in vain?

I became convinced that if I could move only a handful of people to care more for their fellow man, I would achieve something worth while and that it was my duty to try to do just that.

I decided to approach my friend Evelyn Kent to help me write the story of my Holocaust experiences. I had not said more than a few words when she interrupted me and said: Eva, Ive been waiting ever since I first met you twenty years ago, to write your story.

That is how we came to write this book.

PART I

From, Vienna to Amsterdam

1. REFUGEES

For several years after the horror I had the recurring nightmare... I am walking along a sunny street that suddenly becomes sinister. I am about to fall into a black hole... I would wake up sweating and trembling. It haunted me on nights when I least expected it, but I got rid of it by repeating to myself, Its all over, thank God. Im alive.

So I got on with my daily life in England without talking much about the past because I have suppressed the memories for so long.

Now I want to acknowledge the miracle and remember clearly those who helped me to survive Birkenau. I owe them so much and dont want to forget them.

I was born in Vienna on 11 May 1929. My mother, Elfriede Markovits Fritzi for short came from an assimilated middle-class Jewish family. She was vivacious and beautiful, and at the age of eighteen she married twenty-one-year-old Erich Geiringer, an attractive and enterprising Austrian businessman.

It was love at first sight they always told me. My mother was tall and fair, and my father had dark hair, piercing blue eyes and a flashing smile that women found hard to resist. Together they made a striking couple.

Fritzi and Erich Mutti and Pappy to me adored one another and, in the carefree days of their early marriage, they were part of a large circle of newly-weds who would meet at weekends to go hiking in the Austrian mountains. My father was full of energy, a fitness fanatic who enjoyed all outdoor activities and sports.