Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

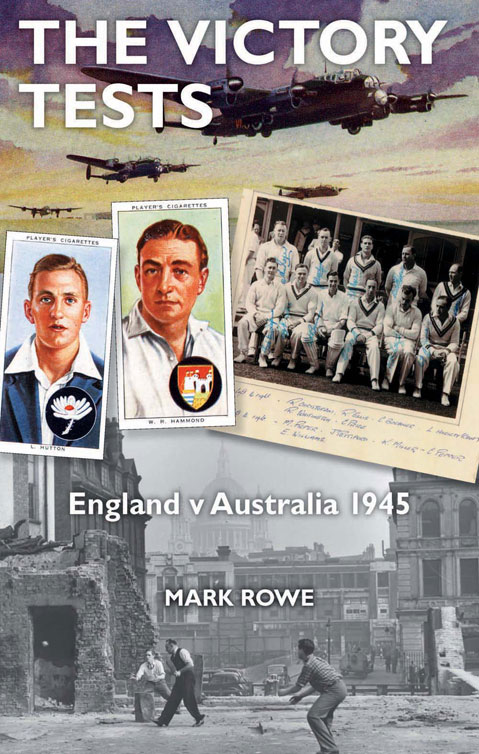

In memory of Allan Duel

Born Banyo, Queensland, 1923

Rear gunner, 460 Squadron Royal Australian Air Force,

Binbrook, Lincolnshire, 19434

Killed in flying accident, near Burton upon Trent, Staffordshire, June 5, 1944

For anyone to kill me hed have to kill

every single Australian,

every single one of them,

every single one.

Ian Mudie, Theyll Tell You About Me

Chapter One

I am not a specialist in the history of cricket. But its pages are presumably studded with the names of those who made centuries rather than of those who made ducks and were left out of the side.

EH Carr, What is History? (1961)

As Bradman batted on, and on, and on, that Monday, March 2, 1936, Ross Stanford must have known he would have only one chance. Stanford was waiting to bat at number six for South Australia against Tasmania. He was the lowest in the order, and the youngest, of three debut batsman. South Australia could take the chance because Tasmania were Australias weakest state, not even in the Sheffield Shield; and a week earlier South Australia had won the shield, thrashing Victoria by an innings, even though Donald Bradman had only scored one.

Tasmania made 158 all out. In reply Jack Badcock, the opener, who had scored 325 in that previous win, was soon out, but by the end of the first day South Australia the hosts were well ahead, on 222 for two. Bradman, ominously, was 127 not out. On the second day, Monday March 2, one of the debutants, 20-year-old Ron Hamence, turned his overnight 60 not out into 121. When his, the third, wicket fell at 387, the other new boy, 18-year-old Brian Leak went in and Stanford became next man, knowing he might have to face the ball after next. He had to wait for more than an hour. Tasmania had no hope of making South Australia bat again, so Stanford the 18-year-old son of an Adelaide market gardener would have only this innings to show what he was made of. At 533 the fourth wicket fell, that of Brian Leak. He had made only 19 in a stand of 146, so fast was Bradman scoring. Stanford walked to the middle to join the worlds greatest batsman.

One of the many strange things about cricket is the definition of good and bad: what makes a debut good or bad, for example? The more runs or wickets, the better. Yet runs against bowlers as utterly beaten and exhausted as Tasmanias would not count for much. Even a big score, if made slowly or in a dull or fortunate manner, could harm a batsmans standing. Equally a small score, if made stylishly or ended by bad luck, could leave a man with some credit. Stanford, alas, could not have done worse if he had tried. He recalled in old age:

When I walked out to bat my knees were wobbling and I had double vision, I was so nervous. And he [Bradman] did the right thing, he knew I was nervous. He was batting when I went in. He had strike and he played about four shots for two, to get me running up and down the wicket, and then he let me have the wicket. I hit it straight to cover and called for a run and there was no hope of a run and he sent me back. I didnt know what I was doing, I didnt think.

At least Stanford did not run out Don Bradman.

Two runs later, at 552, Bradman was out, caught and bowled, for 369. The applause of the crowd of 1,500 must have contrasted cruelly with the quiet or at best sympathetic reception for the failed teenager. South Australia batted on, to 688, and Tasmania went in again just before the end of the day. They were out again before the end of the third day, the end of the season, losing by a colossal so colossal it was needlessly humiliating innings and 349 runs. Stanford was no bowler, so he had no second chance to do anything. If anyone doubts how cruel sport can be, they can see in the Adelaide Oval museum a black and white photograph of the match scoreboard, showing the Dons 369 above Stanfords zero. Black and white, failure and success, were seldom so obvious. Stanford knew it: I didnt do any good, he said.

If at first you dont succeed, try, try again, is an English saying. In Australia in cricket, as in life, if you do not do enough to keep your place, you soon lose it, to someone younger and more promising than yourself, who deserves the chance you once deserved. What happened next to those three young men on debut reflected how well each had done. Hamence had the most successful career, playing three Tests and touring England in 1948 as one of the Invincibles. Leak played a few more times for South Australia. Stanford was not picked the next season, nor the next, nor the next; then war came.

At least for Stanford there were up to six batting places at which to aim five if you count Bradman. Most teams only wanted one slow left-arm bowler like Reg Ellis, so at any step from club to state to country he could find his path blocked. South Australia was the home of the little leg-spinner Clarrie Grimmett, one of the worlds most famous, though he was not picked for the Ashes tour to England in 1938. His fellow state leg-spinner Frank Ward went instead. Any hopeful South Australian slow bowler would have to step into a dead (or rather retired) mans shoes; and Grimmett was still going in his late 40s.

A man with cricket ambitions could move, as Grimmett had. Reg Ellis was one to stay put, despite all his wartime travelling. When aged 91, he was still living in the part of Adelaide in which he grew up, a mile or so from the sea.

When I was young I was a fast bowler. I played with the men up the road a little bit, at Morphett Vale at 14, and in between we used to just bowl at the wicket and I used to bowl down these googly balls and the captain a man called Jack Anderson said, Why dont you bowl spin? I said, I dont know, I have never thought of it, and from then I bowled spin. We came down here to Port Noarlunga and they opened a new oval just over the other side of the river and brought the Sturt cricket team of which Vic Richardson was captain and we played them and nearly beat them. I got five wickets in that game and he invited me down to Adelaide and I started in the Bs. I played five matches in the B grade and got five wickets in each innings, 25 wickets in five matches, and got posted up to A grade and I played for senior colts then, that was an A grade team of all young fellers. I topped the bowling aggregate that year, thats how I got into the team but by that time there was Grimmett and Ward playing for Sturt, two Test bowlers, and I had no chance of getting into the team without they gave up.

What competition two Test bowlers at your local club! Yet cricket in Australias state capital cities the same applied in Melbourne, Sydney and Brisbane thrived because the great men, like Vic Richardson, a Test batsman, took an interest in young talent, as Regs story shows.

And Grimmett was captain of the colts team thats why I got all the gen there. We had a piece on the pitch like a two shilling piece, a little shiny piece on the pitch, over after over trying to hit that on good length. Thats how he got me into bowling on a good length all the time. I never changed the grip on the ball, I had my hands around the seam all the time.

Next page