This book was written to draw attention to one of Clevelands most historic locations and to continue the work of the Early Settlers Association in preserving the burial grounds of many of the early pioneers of the city.

Material for this book has been gathered from many sources, and I hope I do not forget to thank all those who provided information, photographs, or their special collections. Throughout the book I will try to identify the individual, organization, and source of all material rather than in this acknowledgment. Unless otherwise noted, all images are courtesy of the author. I am greatly indebted to the following for their courtesies and help: Janice Petrick, who was a great help in the typing of this book; James Cimperman; Joseph Cimperman; John and Betty Franklin; and Jan Valore. I would also like to thank Ann K. Sindelar, reference supervisor, and Vicki Calozza from the library reference division of the Western Reserve Historical Society Library and Archives; William C. Barrow, special collections librarian from Cleveland State University; Michelle A. Day, president of the Woodland Cemetery Foundation; the staff of the Olmsted Falls Branch of the Cuyahoga County Public Library; Martin Hauserman, chief city of Cleveland archivist; and Veronica Pierce, deputy city of Cleveland archivist.

A special thank you to the Honors and Experimental Learning Program of Cuyahoga Community College (Tri-C), which has undertaken as one of their programs the preservation and restoration of Erie Street Cemetery under the direction of Robert Searson, district director; David A. Bernatowicz, assistant professor in the department of history; and Ashlee Brand, assistant professor and English and Honors Program Coordinator of the Metro Campus, who submitted the project description for the Tri-C program partnership with the Early Settlers Association. Also thank you to the following students in the honors program: Sherrai Watkins, Jasmine Core, Matthew Velotta, Machelle Gay, and Somijata Sakar. It is our hope that this book will assist in their efforts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Annals of the Early Settlers Association of the Western Reserve . Proceedings of the years 1888 to 1959. Published under the direction of the Executive Committee.

Avery, Elroy McKendree. A History of Cleveland and Its Environs . Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1918.

Butler, Margaret Manor. A Pictorial History of the Western Reserve 1796 to 1860 . Cleveland, OH: A joint publication by the Early Settlers Association of the Western Reserve, the Western Reserve Historical Society, and the Lakewood Historical Society, 1963.

Chapman, Edmund H. Cleveland: Village to Metropolis . The Western Reserve Historical Society and the Press of Western Reserve University, 1964.

Ellis, William Donahue. Early Settlers of Cleveland . Cleveland, OH: Cleveland Ethnic Heritage Studies, Cleveland State University, 1976.

Gresser, John A. Burials and Removals Erie Street Cemetery 18401918 . Cleveland, OH, 1919.

Hatcher, Harlan. The Western Reserve: The Story of New Connecticut in Ohio . Cleveland and New York: The World Publishing Company, 1966.

Johnson, Crisfield. History of Cuyahoga County, Ohio . D.W. Ensign & Co., 1879.

Peskin, Allan. North into FreedomThe Autobiography of John Malvin, Free Negro, 17951880 . Cleveland, OH: The Western Reserve Historical Society, 1996.

Reference Guide to Cuyahoga County, Ohio Cemeteries. Western Reserve Historical Society.

Rose, William Ganson. Cleveland: Making of a City . Cleveland, OH: The World Publishing Company, 1950.

Van Tassel, David, and John Grabowski. The Encyclopedia of Cleveland History . Second edition. Bloomington, IN: University Press, 1987.

Wickham, Gertrude Van Rensselaer. The Pioneer Families of Cleveland 17961840 . Vol. I and Vol. 2 (Under the auspices of the Executive Committee of the Womens Department of the Cleveland Centennial Commission1896), Evangelical Publishing House, 1914.

Wilson, Ella Grant. Famous Old Euclid Avenue of Cleveland . Vol. II. 1937.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

THE WESTERN RESERVE

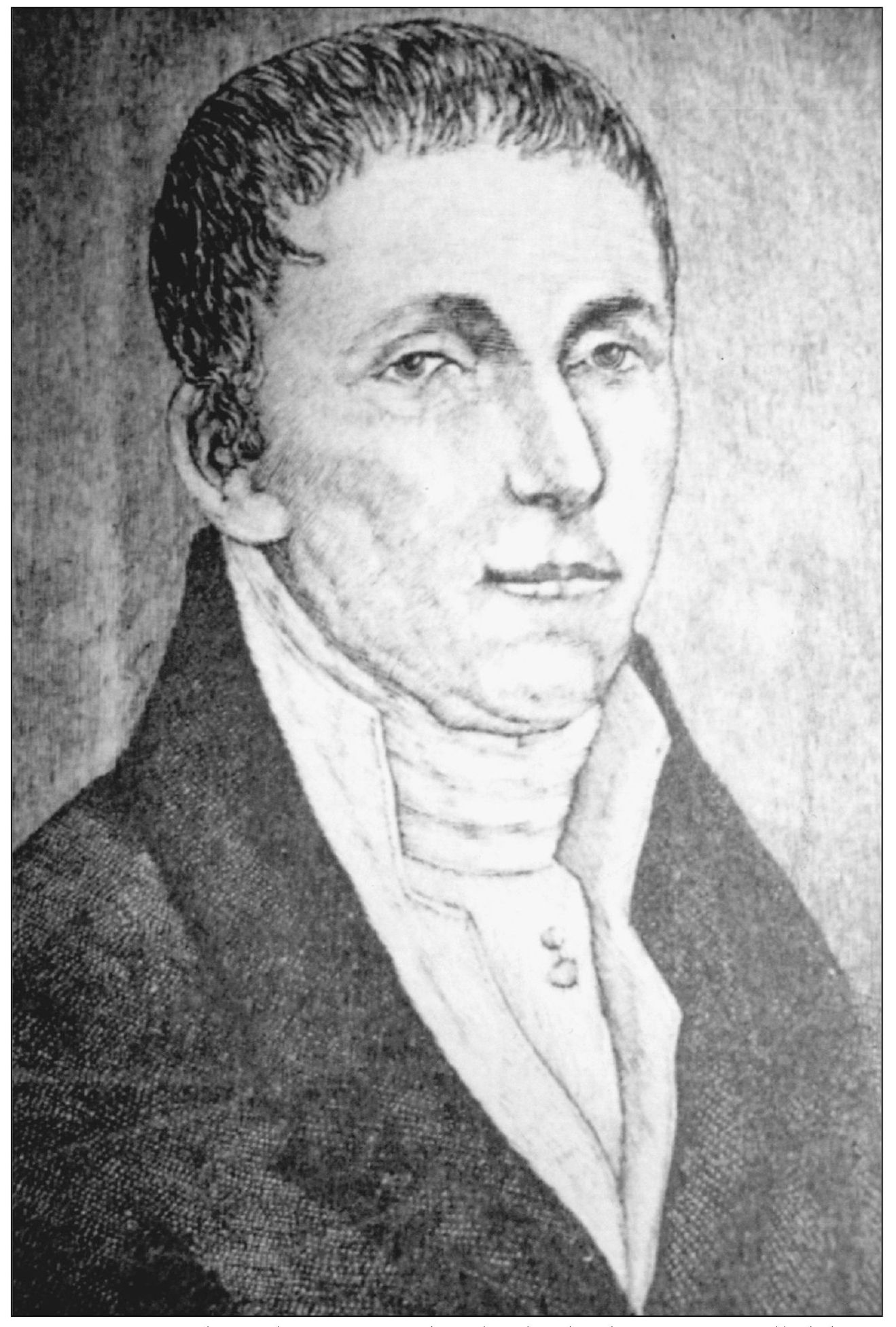

Lorenzo Carter was from Rutland County, Vermont, where at age 21 he bought a farm, cleared the land, farmed, hunted, and fished, and in 1789, he married Rebecca Fuller and fathered two sons.

In 1795, Carter and a companion traveled to Ohio by crossing the Ohio River, then explored the Muskingum River Valley, and wintered in Ohio. In the spring of 1796, they reached the mouth of the Cuyahoga River to search for a homesite on the high ground near the lake.

On May 2, 1797, Carter, Ezekiel Hawley, Elijah Gun, and James Kingsbury arrived with their families to the hardships of the Western Reserve. Because of the harsh winter, Kingsbury returned to New Hampshire for provisions. It took him more than two months to get back. His wife lost their baby to starvation, and she almost died before his return. The hardships of those first settlers were almost unbearable.

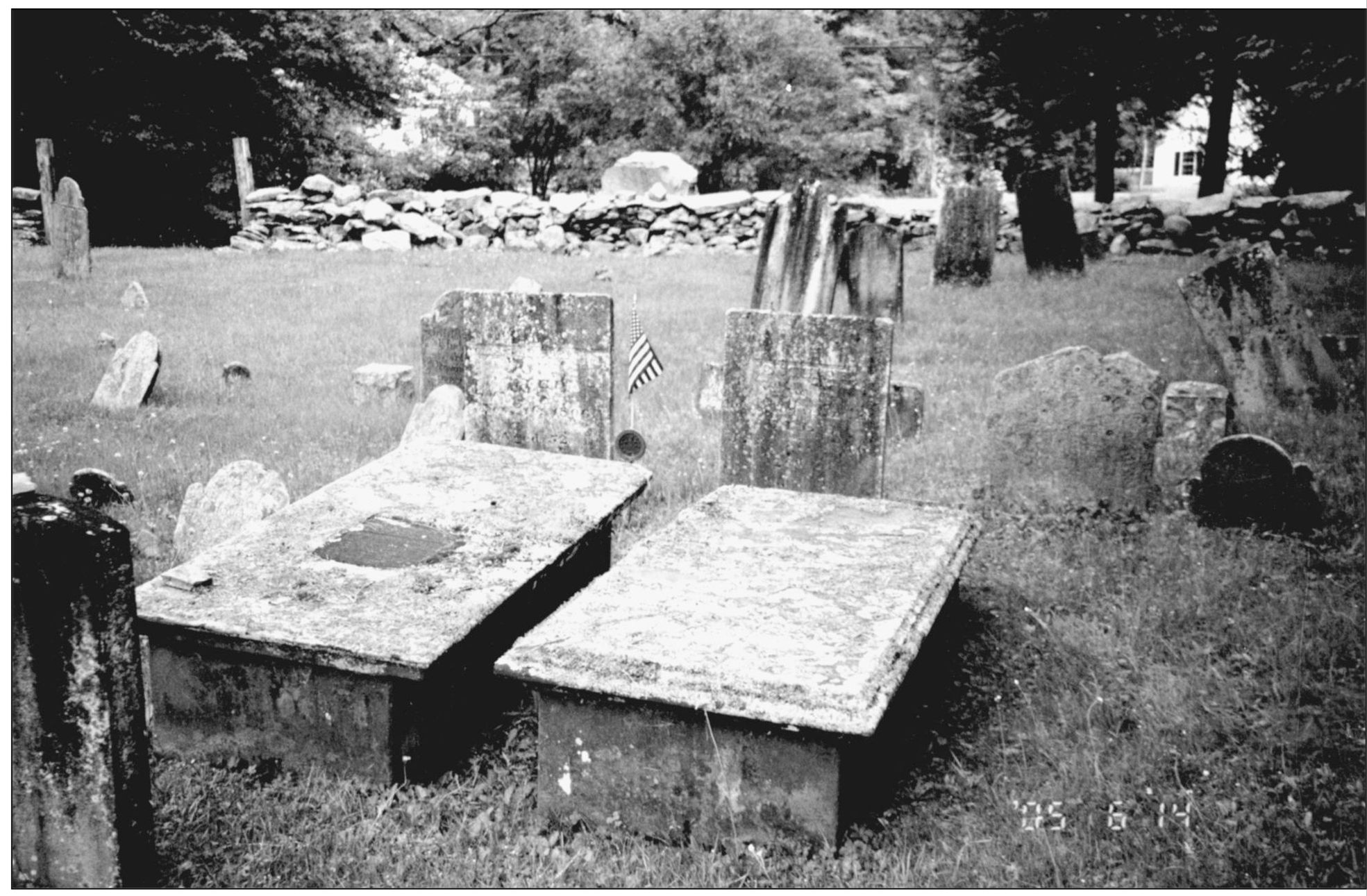

That is why the inscription on the Carter gravesite in Erie Street Cemetery reads, They RemainedOthers Fled. During the early years of the settlement, there was no form of local government; Carter was the law to the Indians and settlers. He and a man named Stephen Gilbert were appointed the first constables of the village.

When Carter reached Cleveland he was 30 years old. He died in 1814 but accomplished a great deal in those 17 years. At his death he was described as a frontiersman, community leader, and tavern keeper. His cabin was used as a tavern where he welcomed travelers with food, drink, and a bed. His cabin was the center of activity in the village. He launched a ferry to carry travelers across the river and traded with the Indians. Carter also built the first schooner for lake trading, making him the father of Clevelands shipbuilding industry. There was no one like Lorenzo Carter; he stood out as a true Cleveland pioneer. As detailed in this book, he, along with many of those early settlers, distinguished themselves in Clevelands early history.

Lorenzo Carter was given the rank of major in the Cleveland militia. He was called the Pioneer of the Pioneers. His young life began with the loss of his father, Eleazer, who served as a lieutenant in the Continental Army. Eleazer returned home from service and died of smallpox at the age of 37, leaving a widow and six children. The oldest was 11-year-old Lorenzo, who continued to farm for his family. In 1789, he married Rebecca Fuller and began to work his own farm in Castleton, Vermont. He was not happy with his life as a farmer and saw the opportunity that New Connecticut had to offer. In the fall of 1795 or early 1796, Lorenzo went west to investigate the new land. He returned home to Vermont in the fall of 1796. In 1797, he moved his family and the family of his brother-in-law, Ezekiel Hawley, along with Elijah Gun and James Kingsbury and their families, to a new life in the wilderness. (Early Settlers Association.)