J URASSIC

M ARY

To two singular young women,

Amanda

and

Brittany

J URASSIC

M ARY

M ARY A NNING

and the

P RIMEVAL M ONSTERS

Patricia Pierce

First published in 2006 by Sutton Publishing

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Patricia Pierce, 2006, 2013

The right of Patricia Pierce to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and

conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 9569 9

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

Acknowledgements

Anyone interested in, or writing about, the life of Mary Anning must give thanks and credit to the substantial research carried out by several individuals. One is William Dickson Lang (18781966), Keeper of the Department of Geology at the British Museum from 1928 to 1938. His wife came from Charmouth, and he retired there to pursue his studies of local natural history and geology. All the while he became more and more convinced of the value of Mary Annings pioneering work, and collected as much information as he could at that date. His approach was scientific with references. As president of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society from 1938 to 1940, he published many articles in the Societys Proceedings, and these are an invaluable source for all writers and researchers on Mary Anning.

John Fowles (19262005), author, novelist, historian and Lyme resident, became Joint Honorary Curator of the Lyme Regis Philpot Museum in 1978, and Honorary Curator from 1979 to 1988. His work on Miss Anning and the history of Lyme importantly focused attention on these subjects.

Today, geologist and historian Hugh S. Torrens, formerly at Keele University, is a leading expert on Mary Anning. He has undertaken much valuable research, and is currently writing his own full biography of Mary Anning. Particularly useful is his Presidential Address of 1995.

Thanks are also due to Jo Draper, Lyme Regis Philpot Museum; the staff of the Earth Sciences Library, and General Library, Natural History Museum; Dr Jenny Cripps, Curator, Dorset County Museum, Dorchester; and the staff of the British Library. Also to Jaqueline Mitchell, Hilary Walford and Jane Entrican, Sutton Publishing; Marion Dent; Kay Hawkins; Bridget Jones; and my agent, Sara Menguc.

Quotes from Finders, Keepers by Stephen Jay Gould, published by Hutchinson, are reprinted by permission of the Random House Group Ltd.

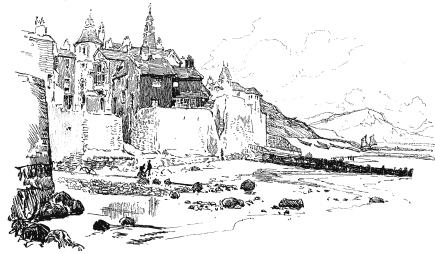

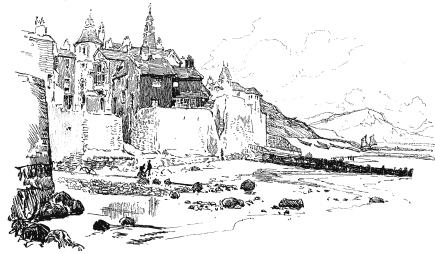

Lyme Regis from the sea.

Introduction

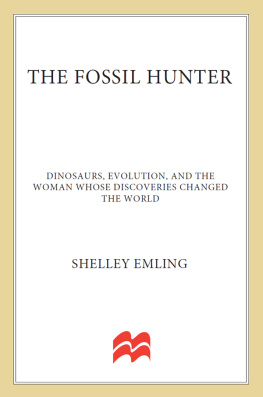

It sounds like the beginning of a fairy tale the story of a poor cabinet-makers young daughter who discovered an important and massive fossil at Lyme Regis, Dorset. Mary Anning (17991847) unearthed the first complete fossilised skeleton of a fish lizard or Ichthyosaurus, when she was about 12 years old. However, Marys life was no fairy tale, but a struggle against near-impossible odds, although the mystery surrounding some of her life does imbue her story with a certain mythical quality.

In Lyme Regis Marys future path was set when she was still a girl, and she followed it throughout her life, finding a sequence of some of the earliest palaeontological specimens in the world. For Lyme is situated on an exceptionally fossiliferous coastline, where fossils the remains or traces of animals and plants preserved by natural processes were, and still are, to be found in abundance, and often of enormous size. But at that time few people knew what these strange bones and objects were or how they had come to be there.

In her twenties Mary discovered the first complete British Plesiosaurus giganteus (1823/4), which became the type specimen (that is, it set the definitions for its category for future reference in identifying further finds). She then found the first British example of the strange winged pterosaur, named Pteradactylus macronyx (1828) (renamed Dimorphodon macronyx), and then the new species Plesiosaurus macrocephalus (1828). That was followed by a strange new genus of fossil fish, Squaloraja (1829), another type specimen. There was much more. She was among the first to realise that the small fossils named coprolites found in abundance on the foreshore were actually the fossilised faeces of prehistoric monsters. The huge marine lizards were contemporary with dinosaurs, although some of this story happened before dinosaurs were found, identified as such and so named.

Those professionals who study fossil animals and plants, the palaeontologists, have documented the finds, and it is for such scholars to analyse and explain the specimens in detail. While I am drawn to the diversity and beauty of the geological features of our planet, my interest in Mary Anning is as a woman: an exceptional woman, trapped in the stratified society of the first half of the nineteenth century.

Her achievements were remarkable by any standards, but especially so because she was born and bred in lowly circumstances from which there was little chance of escape. Mary was lower class, female, uneducated, unmarried and a dissenter one who did not belong to the established Church of England. Lyme Regis was a remote place, its inhabitants socially hampered by the barrier of a strong Dorset accent. This impoverished spinster had to earn her own living, and it was to be in an unusual and dangerous way: by finding, excavating and then selling fossils both to casual seaside visitors and to important collectors and museums in Britain and Europe. Any one of her handicaps could have been enough to scupper her chances; however, even though she was not properly recognised as a socially well-placed man would have been she did succeed to a large degree.

In spite of every disadvantage, Marys curiosity, intelligence and industry shone through to such an extent that her story is inexorably welded to the history of fossils found around Lyme Regis, mainly, although not exclusively, of the Jurassic Period, 200 to 145 million years ago.

Researching her discoveries was vital to my understanding of Mary; learning something of her subject and giving rein to my interest helped me to appreciate what fired her enthusiasm and determination. I hope the information gathered here to tell her story will similarly inspire the reader to look further, in acknowledgement of her great accomplishments.

A group of extraordinary and multi-talented men touched Mary Annings story, and some introduction to them is as essential to the understanding of her circumstances as are the very fossils they collected so obsessively. Pioneer geologist Henry De La Beche (17961855) founded the Geological Survey of Great Britain; irrepressible William Buckland (17841856), an unforgettable character and a founder of the Royal Geological Society, was the first Professor of Geology at Oxford, and became known as the Father of Palaeontology; William Conybeare (17871857) first described many of the Lyme fossils; Roderick Impey Murchison (17921871) defined and named the Silurian, Devonian and Permian Periods of geological time, and wrote 350 books, reports and papers; Adam Sedgwick (17851873) was the first Professor of Geology at Cambridge, a position he held for fifty-five years, and he introduced the term Devonian (with Murchison).

Next page