ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Certainly no story about the Little Santa Clara River Valley can be told without those making history and those keeping it.

I am humbled by the chain of good people, stretching back centuries, who have passed along the culture, fable, wit, and courage along with their questionable decision-making. There are the usual suspects within the endless spectrum of the Santa Clarita Valley of pirates, volunteers, resume-building bureaucrats, and saints to thank. At the top of the list is Leon Worden, who, for decades now, has joined historians A. B. Perkins and Gerald Jerry Reynolds in quietly and tirelessly adding to the growing coffers of the SCVs historical fortune.

Someone wise once said that we only die after the last person remembers us. I owe Pat Saletore, executive director of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society, a huge debt. She not only managed to dig up most of these dusty and fading memories but also labored like a benign shaman to scan the images for posterity.

I have lived most of my life in this valley and marvel at how much the people give to the community. The SCV Historical Society is a marvelous group composed of Johnny and Jane Appleseeds, who are planting history for future generations and sharing the SCVs rich lifewith just enough wickedness to make them interesting.

The mighty Signal is that swashbuckling little daily newspaper now nearly a century old. For a quarter century, during the valleys most dynamic change, the Holy Trinity at the periodical was Scott, his wife, Ruth, and their son, Tony Newhall. They reminded us, daily, of the papers motto: Vigilance Forever. That translated to actively caring for our history.

What follows is but a thumbnail of the story of the Santa Clarita Valley. With but 200 or so graying photographs and a few thousand words, its impossible to capture the myriads of tales, legends, statistics, and deeds of so many. A proper volume would be encyclopedic. For those who do not appear in the following pages, do not despair. The saga of the SCV is ongoing.

Thanks to these remarkable people. The Santa Clarita shall not be forgotten.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

A MILLION YEARS, THEN VOICES

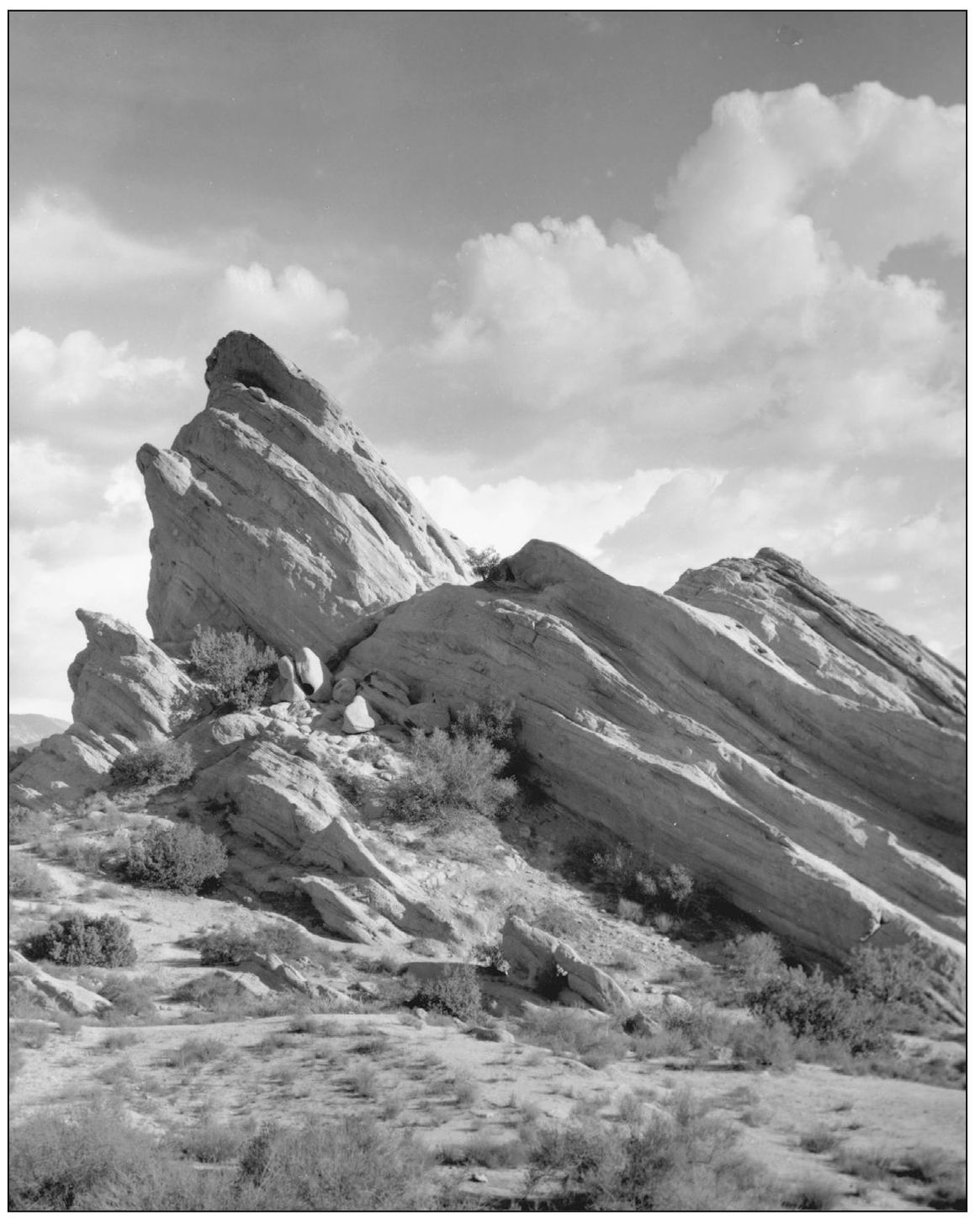

Imagine eons without the sound of a human voice. Primitive man reached the Santa Clarita Valley about 18,000 years ago. Some lived at Vasquez Rocks, which today is a Los Angeles County Park. Grinding holes and bunks can still be seen. A developer tried to buy Vasquez Rocks and put up condos. He wanted to paint, in giant white letters, the new name: Moon Valley. (Courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

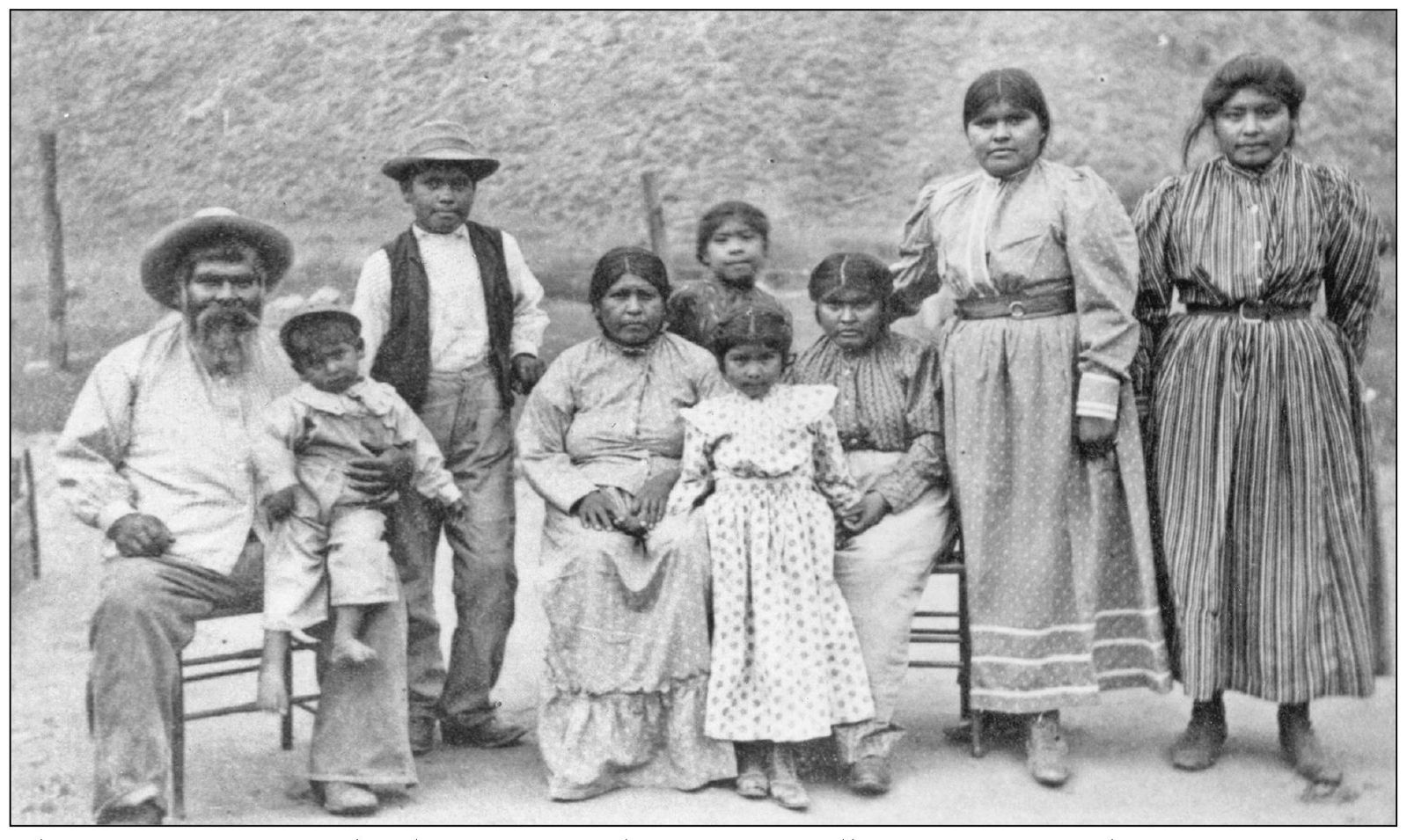

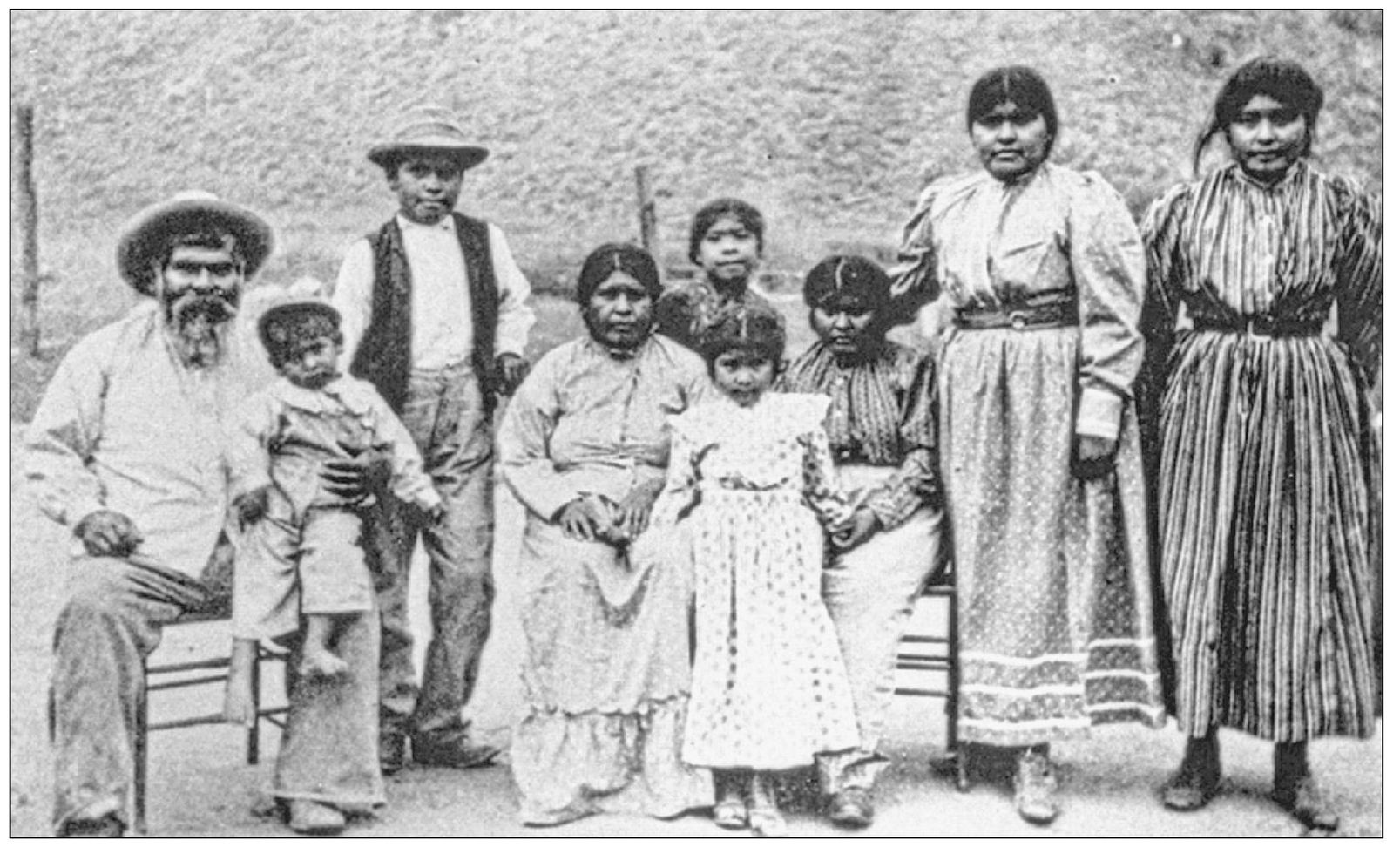

About 7,000 years ago, the climate was cooler. One can still see remnants of those ancient conifer forests atop Newhall Pass and Bear Divide. Around 450 AD, the Tataviam, a branch of Shoshone, migrated to the SCV. Geographically isolated, they spoke with a guttural clicking sound. Juan Jose Fustero and his family were the last of the peoples. (Courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

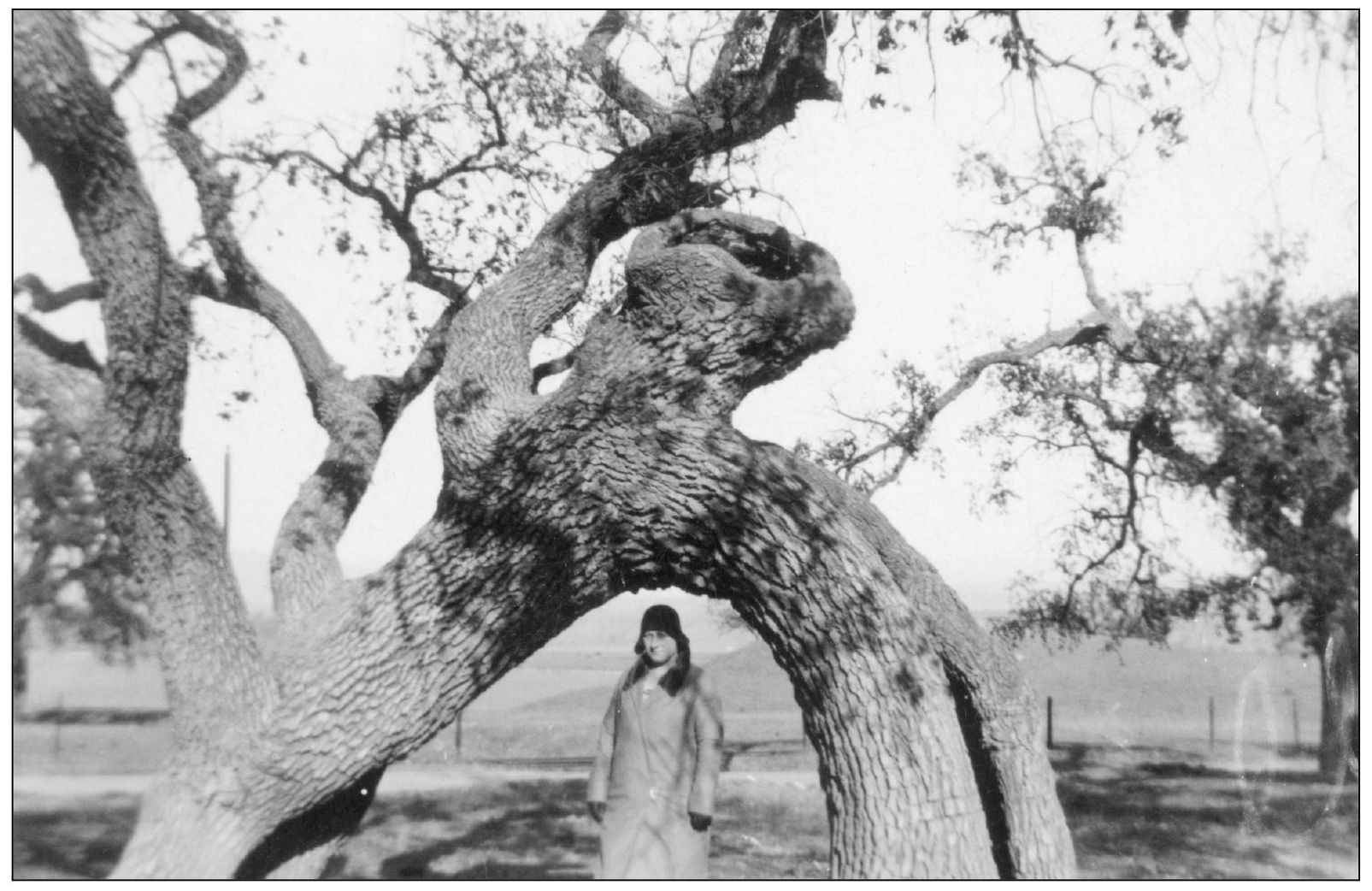

Some old-timers call the SCV the navel of the universe. It was the hub of ancient, vast Native American trade routes. Chinese general Homer Lea, in the early 20th century, named the SCV one of the top 10 military targets on earth because of the key intersection of roads and rails. This Marker Tree is still in Stevenson Ranch and was bent by Native Americans as a road sign. (Courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

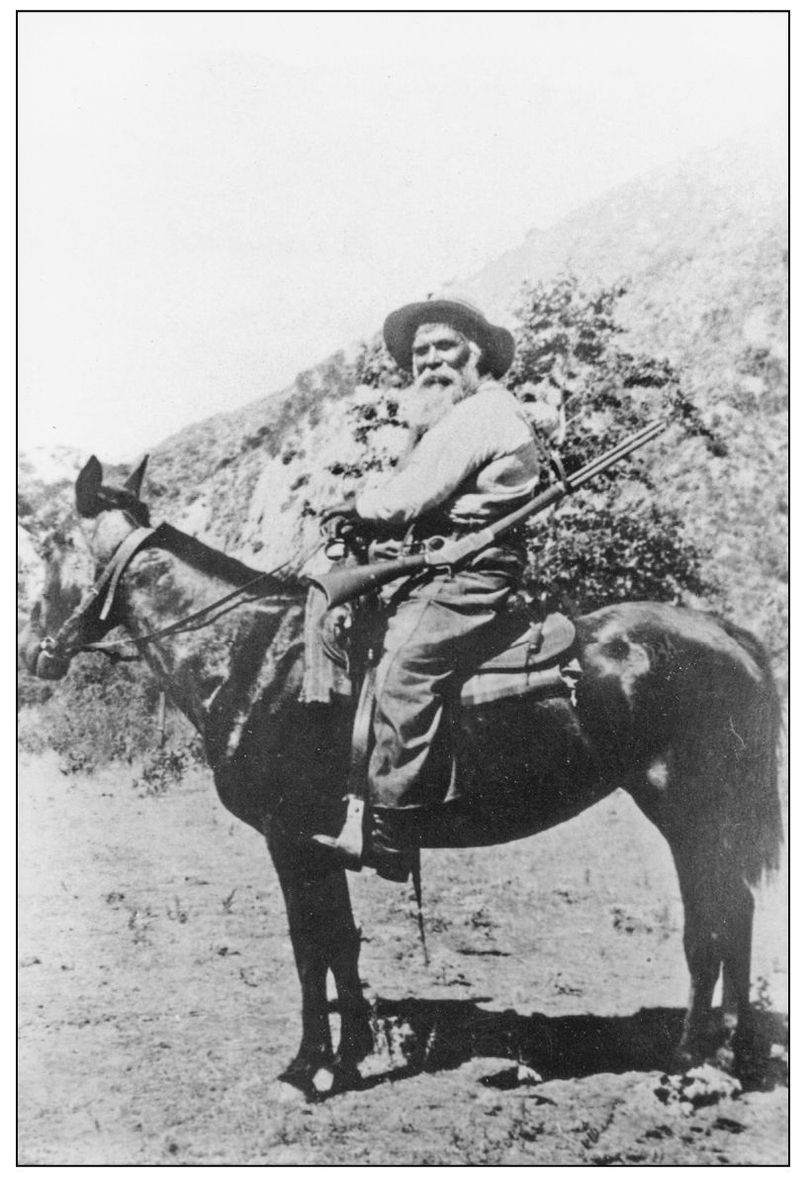

The Tataviam were the SCVs dominant Native American peoples, and Juan Jose Fustero was the last full-blooded male. He was a gifted horseman. Barely 5 feet tall, he weighed 350 pounds and sported a protruding hernia. Locals believed Fustero found Joaquin Murrietas lost treasure because he would show up in town regularly with $20 gold pieces. In 1921, his family found his heat-bloated corpse and a small fortune underneath. (Courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

Sinforosa Fustero (right) was mother to Juan Fustero and believed to be the last full-blooded Tataviam woman. In her final years, around 1910, she lived in a tent on Walnut Street. The Tataviams homeopathic cures included swallowing red ants to cure dysentery and the yerba santa plant as a painkiller. Like most Southern California tribes, they rarely fought against other Native American communities. (Courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

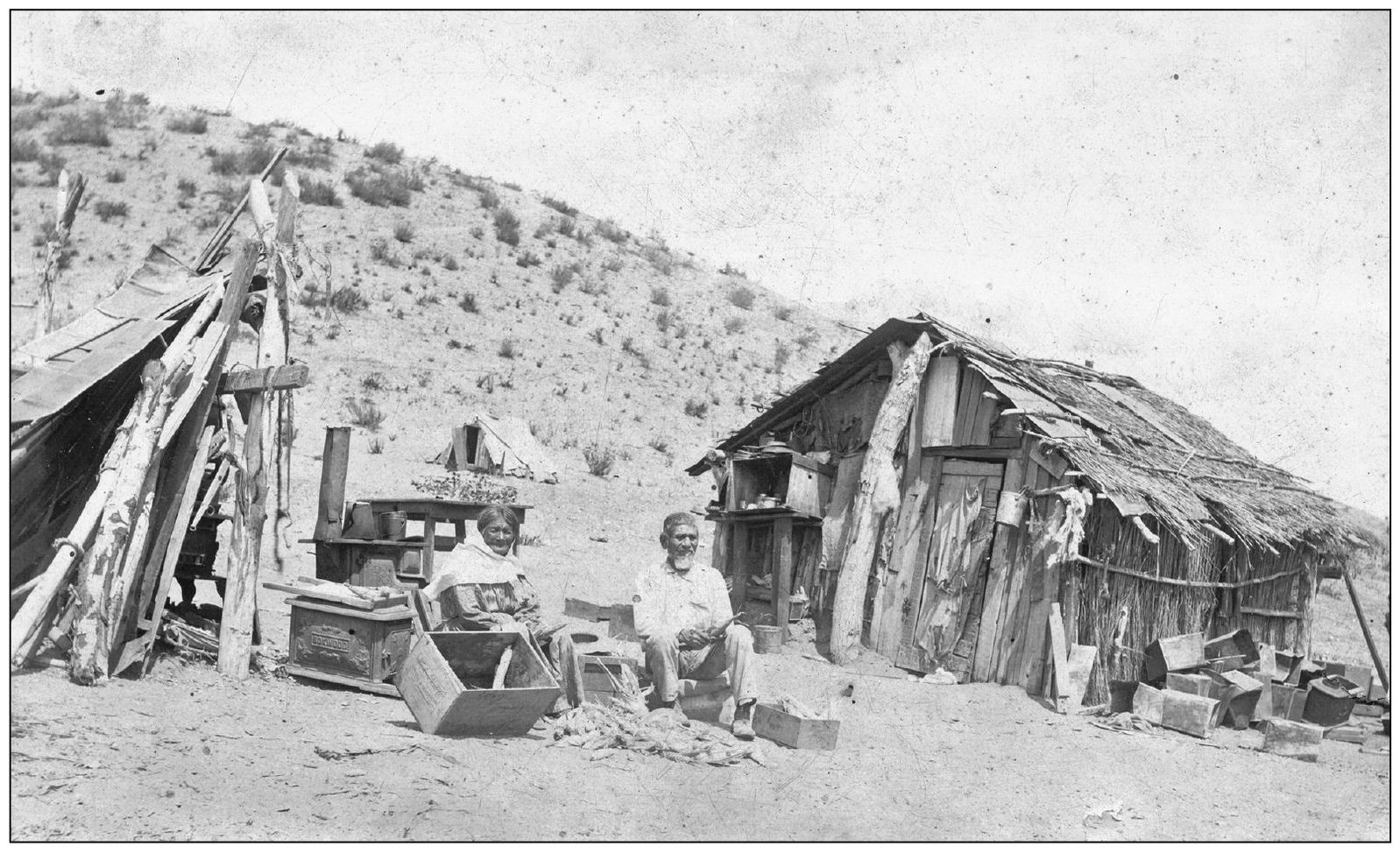

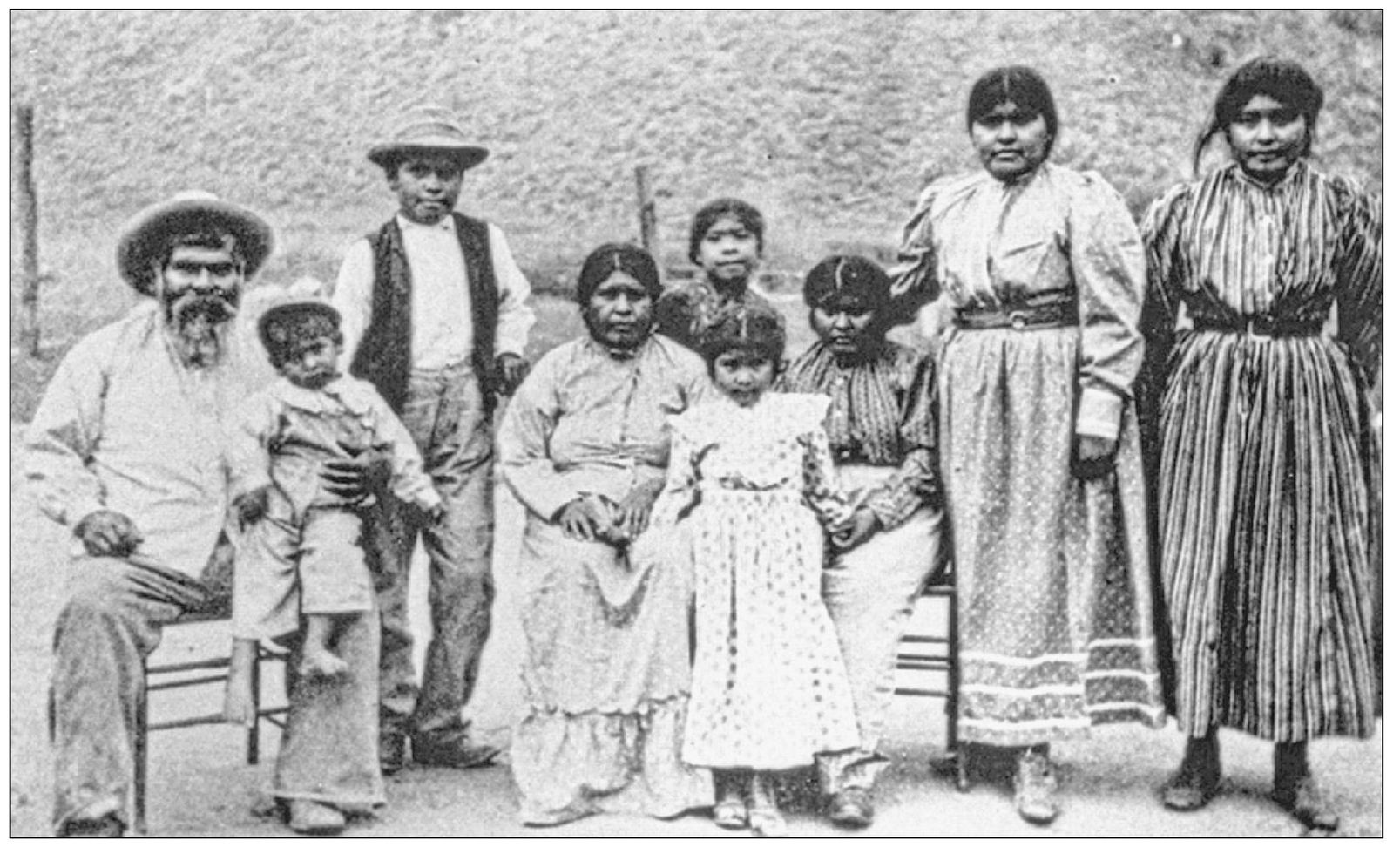

Because of a misunderstanding in the 1920s, the extinct local Native Americans were called Alliklik . Translated, it means naked stuttering dirt-eater. In the 1970s, it was discovered that the correct name is Tataviam dwellers of the sunny slope. They were scattered in about 25 semi-permanent villages. Two population figures have been given: 500 and 1,500. The Tataviam divided themselves into two clans, coyote and mountain lion. Neither could marry within their clan. The Tataviam had a creation story similar to Genesis. Fustero and his wife are seen at his lean-to in the image above. When a wickiup became too buggy, it was burned and a new one built. Fustero ended up living near Piru Creek but was cast out by religious publishing mogul David Cook, who was the author of The Garden of Eden and was known as the Father of Piru. Fustero and his family are seen in the image below. (Both courtesy SCV Historical Society.)

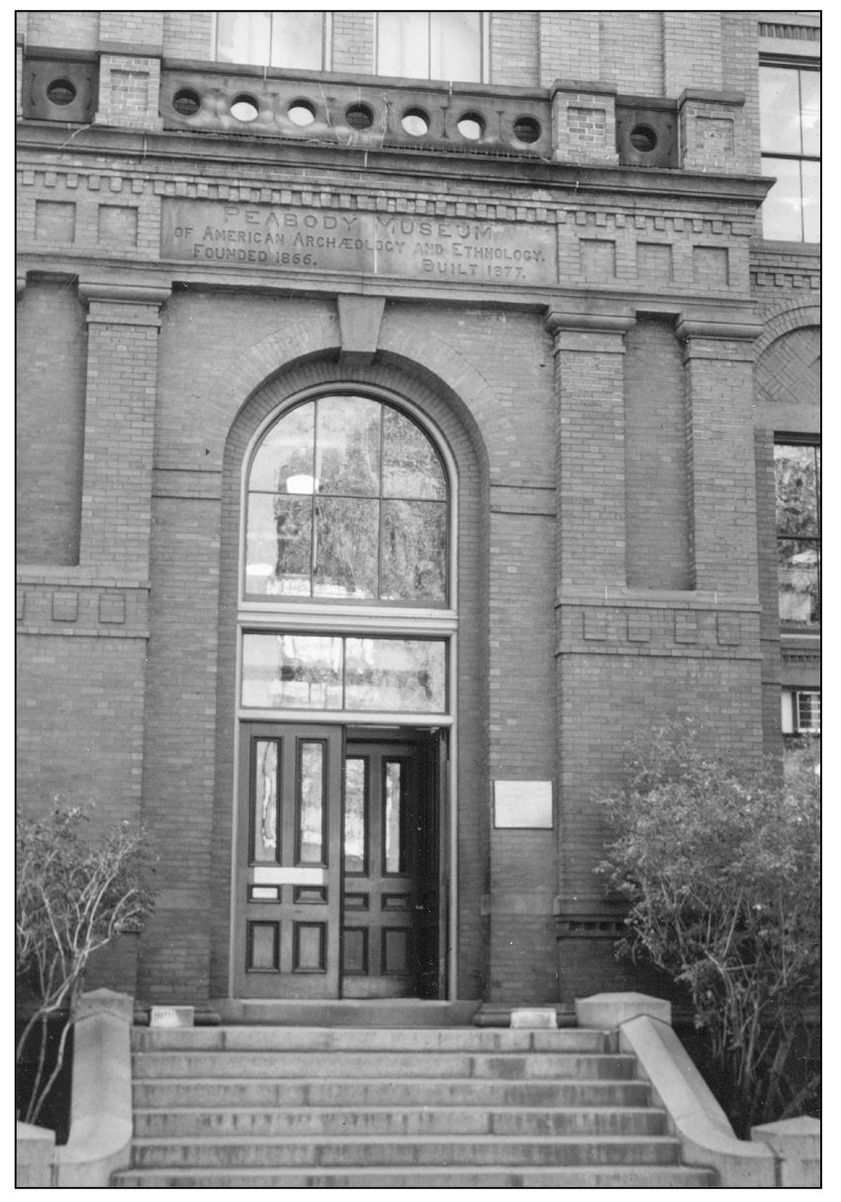

Much of what is pieced together about the Tataviam comes courtesy of teenage brothers McCoy and Everett Pyle. Near the Chiquita Canyon landfill today, they found a cave in 1884 stuffed with what was called one of the most significant caches of Native American artifacts. It is called Bowers Cave after Dr. Bowers, who bought the cache from the boys. The hundreds of items currently are stored in the Peabody Museum at Harvard University. Perhaps Mac suffered some Tataviam curse for raiding the tomb. When he first entered the cave, he wrote, in charcoal, Mac Coy, 1884. He became a local lawman, and just a few years later, some local thug snuck up behind him in Castaic, put a revolver to the back of his head, and shot him to death. (Both courtesy SCV Historical Society.)