BEN-GURION

Ben-Gurion

Father of Modern Israel

ANITA SHAPIRA

Translated from the Hebrew

by Anthony Berris

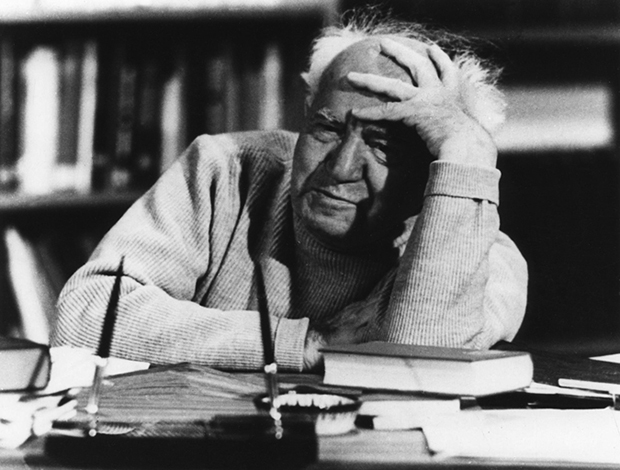

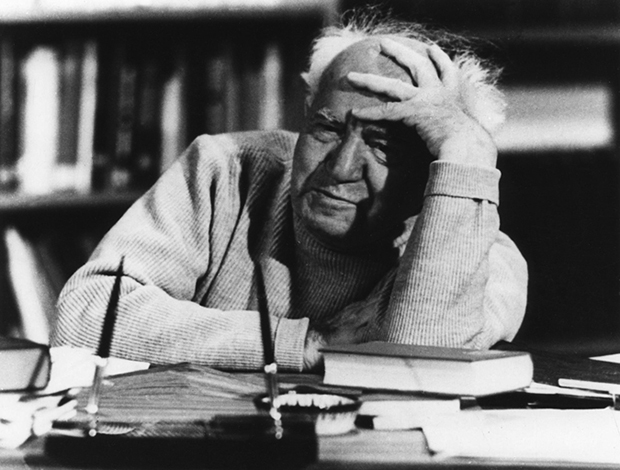

Frontispiece: Ben-Gurion in 1971.

Copyright 2014 by Anita Shapira.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson Oldstyle type by Integrated Publishing Solutions.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Shapira, Anita.

Ben-Gurion : father of modern Israel / Anita Shapira ; translated from the

Hebrew by Anthony Berris.

pages cm (Jewish lives)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-18045-9 (alk. paper)

1. Ben-Gurion, David, 18861973. 2. Prime ministersIsraelBiography.

I. Berris, Anthony, translator. II. Title.

DS125.3.B37S53713 2014

956.94052092dc23

[B] 2014010381

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992

(Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

PREFACE

PAULA BEN-GURION STOOD at the entrance to the wooden cottage in Sdeh Boker, blocking the door. What do you want? she barked at me.

I have an interview with Mr. Ben-Gurion, I replied, embarrassed.

She moved aside to let me pass. Dont tire him! she ordered.

I was working on my first research project, which dealt with the Hashomer (Watchman) organization. I wanted to clarify a point regarding the clash between former Hashomer members and Ben-Gurion, then general secretary of the Histadrut labor organization. So I wrote to the retired leader, asking to meet him and discuss this question. I was a completely unknown scholar, a young woman of no consequence. Nevertheless Ben-Gurion replied in his own writing, on a page from his enumerated notebooks with sheets of carbon paper between the pages. He agreed to meet, and even consented to see me on whatever day was convenient for me. I brought my husband and toddler son, and we drove south from Tel Aviv in our small Fiat 600. It took us at least three hours to reach Sdeh Boker over bumpy roads. My son enjoyed chasing birds in the fields, and my husband chased him.

When I crossed the threshold of the famous cottage, Ben-Gurion received me very graciously. He opened his diary to the year in question and talked at length about the Hashomer case. I was overwhelmed by the grand old man. I stayed with him for more than two hours. Then my family and I started the long drive home. It was only when we reached Tel Aviv that I realized that he had not answered my question.

Since then I have researched many subjects, and Ben-Gurion, a central figure in Zionist history, has been a constant presence in my work, but I have not written directly about him before. He was the second most important figure in my biography of Berl Katznelson, his friend and colleague in leadership. He was the person who clashed with the Haganah general command during the War of Independence, who brutally dismissed Yigal Allonthe golden boy, the best field commander in the warall topics I devoted books to. Only in a few articles did I give him first place, such as one I wrote about his attitude toward the Bible and its role in Israeli culture. So it seems time to finally make him the central figure, here in this biography.

Ben-Gurion attracted many writers and biographers, during his lifetime and after; they include historians, journalists, admirers, and antagonists. As while he lived, so ever after he cast a larger-than-life shadow, and many of these writers could not rid themselves of their sympathy or hatred, old grudges or adulation. Most prominent among his biographers are Michael Bar-Zohar and Shabtai Teveth, whose works I read very carefully and made use of in my own study. Other historians wrote about specific issues in his career, such as his decision to launch the Sinai Campaign, his relationships with intellectuals, his attitude toward the Diaspora, and so on. I have read these works, of course, and made use of them elsewhere, but here I relied mostly on my own past studies. I did much new research into the period after 1948, which Teveth did not cover and Bar-Zohar dealt with only partially. I was given access not only to Ben-Gurions archive in Sdeh Boker, which is online, but also to his files in the archives of the Israel Defense Forces, where I found many interesting documents, especially letters.

While Ben-Gurions public persona has been the subject of many works, I have tried to sketch his private persona, as well as the long process of his development into a national leader and one of the most significant figures of the twentieth century. Ben-Gurion tended not to display his feelings, and tracing his inner self is difficult. I hope this work will add a page with a different perspective to the large collection of works dealing with his achievements, failures, and role in history.

BEN-GURION

1

Plonsk

IN 1962, a woman from the town of Plonsk, Poland, who had emigrated to Palestine went back for a visit. On returning to Israel she sent a letter to Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, also born in Plonsk, describing what she had found: the destruction of Jewish Plonsk, as Ben-Gurion put it in his reply. Only three of the towns Jews remained. The magnificent synagogue and the three Jewish religious schools were completely destroyed, and the cemetery was uprooted. The market was still there, but no Jews displayed their merchandise. With much pain and restrained nostalgia, Ben-Gurion inquired what had become of his fathers house and whether the garden behind it still existed. The rupture between now and then caused by World War II, the Holocaust, and the subsequent communist regime was total. An entire world had been made extinct and existed now only in memories and images.

In his later life Ben-Gurion used to glorify the memory of

Plonsk sat on a minor road off the highway between Warsaw and Gdansk. Although it was only sixty-five kilometers from Warsaw, the journey to the capital took over three hours. In the early 1900s the railway had not yet reached Plonsk, and there was no paved road to the town. It had no running water, and sewage flowed in the streets. The winds of the Haskala (Jewish enlightenment) were blowing in Plonsk, but as might be expected in such a backward place, most of its Jews were piously observant, and progress was only relative. There were three Jewish religious schools and numerous heders (Jewish elementary schools), including both traditional schools and progressive, relatively modern institutions that nevertheless did not teach Russian or mathematics, despite the Russian authorities demand that the children also be taught secular subjects. The town did not have a

Next page