CONTENTS

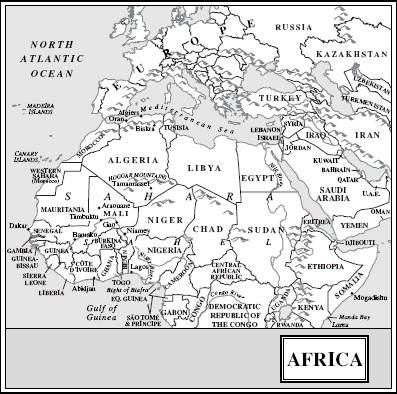

1. Americas African Rifles

With a Marine Platoon, African Sahel, Summer 2004

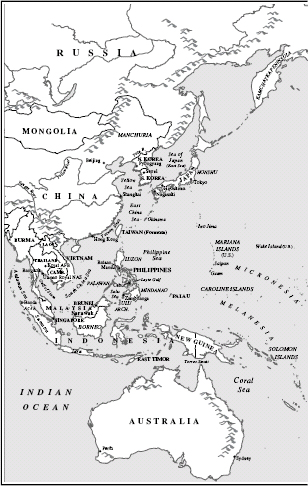

2. Alaska to Thailand: The Organizing Principle of the Earths Surface

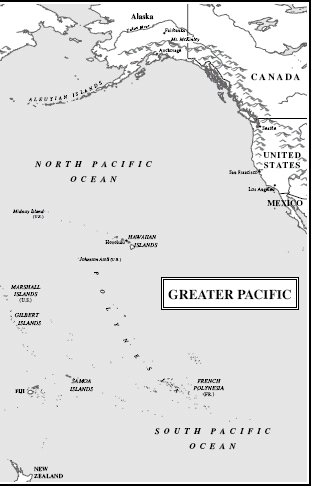

Pacific Ocean, Autumn 2004

3. A Civilization unto Itself, Swishing Through the Crushing Void

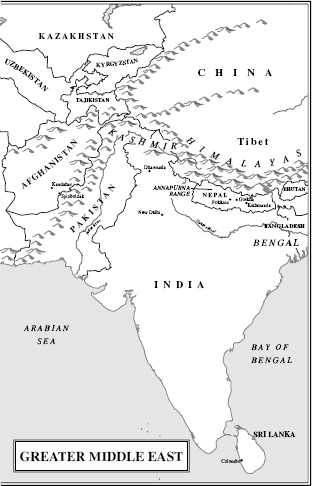

On a Navy Destroyer, Indian Ocean and Andaman Sea, Winter 2005

4. Geeks with Tattoos: The Most Driven Men I Have Ever Known

On a Nuclear Submarine, North Pacific Ocean, Spring 2005

5. NATOs Ragged Southern Edge

With Army Special Forces, Algeria, Summer 2005

6. The Gurkha Standard

Nepal, Summer 2005

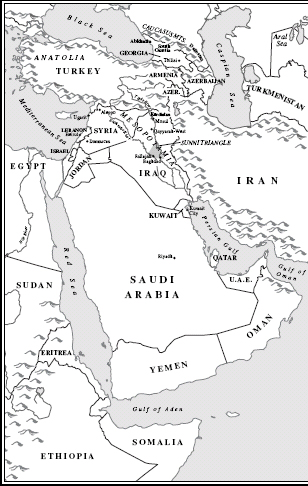

7. Tribal Mafias

With an Army Stryker Brigade, Iraq, Autumn 2005

8. A Dependable Blue-Collar Plane

With an Air Force A-10 Squadron, Thailand, Winter 2006

9. Timbuktu, Soviet Stonehenge, and Gnarly-Ass Jungle

Mali, Georgia, the Philippines, and Colombia, Winter and Spring, 2006

10. The Big Glider and the Jagged Boomerang

With Air Force Predator and B-2 Pilots, Las Vegas and Guam, Spring 2006

11. The Morbid Tyranny Out of Antiquity

With U.S. Forces, Korea, Summer 2006

To John and Martyna Fox

I could have a well-paying job with a company like DuPont, and be home every night. But life is supposed to have meaning. Whenever Im ready to collapse on the bridge at 3 a.m., I think of the chiefs [chief petty officers] retirement ceremony and the clanging bell that declares, While others slept, you stood the watch.

Navy Ensign Zephyr Riendeau of Colebrook, New Hampshire

A sub[marine]s not a job; its a way of life. Its easy to mold a sailor into anything you want him to be, because on a sub he cant go anywhere. Hes yours.

Navy Senior Chief Petty Officer Anthony Maestas of Salt Lake City

I was embedded with the 1st Battalion of the 32nd Regiment of the 10th Mountain Division, based out of Fort Drum, New York, and fragged out to the 82nd Airborne Division. Thats what I do, thats my identity. I am an Air Force pilot who serves the Army. Providing CAS [close air support] for the 10th Mountain Division was the defining moment of my life. I befriended and loved people, and saw them killed. I was a new captain and there was this very experienced first lieutenant who would never call me anything other than sir. That does something to you. He had been married for a few weeks and then was killed by an IED [improvised explosive device].

Air Force Capt. Brandon Custer Kelly of Cairo, Georgia

I will fortify the moral high ground. People will attack me with stories about Abu Ghraib and the killing of Filipino civilians a hundred years ago by American troops, actions which I cannot defend. And I will respond that my troops can build a school, or fix a little girls cleft palate at a MEDCAP [medical civil action program], whereas all the guerrillas of Abu Sayyaf and Jemaah Islamiyah can offer is a suicide vest. I will build my fortress on deeds, because I know that the only force protection I have is the goodwill of civilians. All the guns in the world wont keep an IED from going off.

Army Col. Jim Linder of Fort Lawn, South Carolina

THE BETTER THEY FOUGHT, THE BETTER RELIEF WORKERS THEY BECAME

Stage by stage, the USS Benfold, a guided missile destroyer, closed the distance with the USNS Rainier, a fast combat support ship: 9,000 yards, 8,000 yards, until, after fifteen minutes, the $1 billion steel behemoth came alongside a ship of even greater proportions, loaded with fuel and provisions. Only 160 feet of water now separated these two gray armored spirits of the industrial age. There was a deafening holler of wind as a churning funnel of rapids formed between us and the Rainier, the explosions of foam concentrating, it seemed, all the energy of the ocean. One by one, lines were shot across the Benfolds deck from the Rainier and hauled in by deck apes and deck monkeys, the lowest-ranking enlisted sailors, who latched them onto fairleads, pelican hooks, and pulleys. It had begun with a single red string fired by an M-14 rifle, to which a rope was then attached, followed by a cable. Soon gigantic fuel hoses and pallets were sliding from the Rainier across to the Benfold, as deck apes with blue construction helmets and orange vests began a snake dance with the cables that controlled the line tension, so as to carefully bring in the groceries. A chief petty officer boomed orders over a loudspeaker while another communicated with the Rainier in whole sentences through signal flags. The world was a roaring black abyss sprinkled with a flurry of glowing yellow lights from the two vessels. It was like a docking in space.

Few navies in the world could perform an Un-Rep (underway replenishment), which depends less on technology than on sheer seamanship.

Bosuns Mate Chief Andrew Rader of Newark, Ohio, orchestrated the snake dance. Reconnect the fucking messenger [cable], and stop acting like a fucking girl, he hollered over to a member of his crew, immediately giving a fatherly pat and apology to the female sailor beside him. I didnt mean that, he told her. He paused for a second only. Flake the line down, fuckstick. Remove the hook from the ass. Heave!

I was in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Sumatra. It was January 2005 and the Benfold had just completed its part in the tsunami relief effort. It was now heading for the Strait of Malacca, to help patrol the worlds busiest shipping lanea choke point crucial to international trade, and hence to globalization itself.

For these sailors, places like Iraq and Afghanistan were at the edge, rather than at the forefront, of their consciousnesses. They and so many others in the U.S. military were busy with the additional responsibilities of a great powerdisaster relief, protecting the sea-lanes, training indigenous troops, fighting terrorists on several continents, adapting to the rise of new hegemons, and so on. The two wars in the Middle East might not have been going well, but you would have barely noticed it aboard Americas surface warships and submarines, scattered over the worlds oceans; or among pilots on deployment from Alaska to Antarctica and many places in between; or among soldiers and marines on small missions across Africa, Asia, and South America. To go from several weeks aboard a submarine in the Pacific with the U.S. Navy to several weeks in the center of the Sahara Desert with the U.S. Army, as I did one time, was normal, given the scope of so many simultaneous operations.

Next page