Robert D. Kaplan

IMPERIAL GRUNTS

THE AMERICAN MILITARY ON THE GROUND

To the memory of Marine 1st Lt. Joshua Palmer of Banning, California, born November 28, 1978, killed in action April 8, 2004

And to all the other U.S. Marines killed or wounded during the fighting in Fallujah, Iraq, in April 2004

Major Victor Joppolo, U.S.A., was a good man. We have need of him. He is our future in the world. Neither the eloquence of Churchill nor the humaneness of Roosevelt, no Charter, no four freedoms or fourteen points, no dreamers diagram so symmetrical and so faultless on paper, no plan, no hope, no treatynone of these things can guarantee anything. Only men can guarantee, only the behavior of men under pressure, only our Joppolos.

John Hersey,

A Bell for Adano, 1944

Imperialism moved forward, not as a result of commercial or political pressure from London, Paris, Berlin, St. Petersburg, or even Washington, but mainly because men on the periphery, many of whom were soldiers, pressed to enlarge the boundaries of empire, often without orders, even against orders.

Douglas Porch, professor at the Naval War College, Newport, Rhode Island, 1996

In a campaign against Indians, the front is all around, and the rear is nowhere.

Erasmus D. Keyes,

Fifty Years Observation of Men and Events, 1884

He was a lieutenant colonel in the First Marine Expeditionary Force (I MEF as it is written, and One MEF as it is spoken) stationed at Camp Pendleton, California. I met him before he left for the Persian Gulf in the autumn of 2002. He had just been injected with anthrax vaccine, and had been taking malaria pills for many months of his life, during missions to Africa to train local armies. He told me that in the markets of the CongoBrazzaville condoms were used as sacks for pencils, fruits, everything except what theyre supposed to be used for; that tribal patronage, not merit, often decided promotion in the Kenyan army; that North Korean diplomats in Africa received little financial support from their government, and in order to be self-sufficient dealt in drugs and prostitution. His skin was the color of clay under his high-and-tight crew cut, with taut cheeks and a get-it-done expression: an ancient sculpture in digital camouflage, except for the point of light in his eyes. The Romans, by their rites of purification, accepted and justified the world as it was, with all its cruelty. The Americans, heir to the Christian tradition, seek what is not yet manifest: the higher ideal. Thus, he was without cynicism. Rather, his honesty made self-delusion impossible.

The century is only two years old, he told me, and look at whats happened. That al-Qaeda incident on September 11 was somewhat significant. But we may have nuclear attacks and disease outbreaks that will take many more lives, and which will get us deeply involved on the ground in countries still obscure to us, the way September 11 got us involved in Afghanistan and Pakistan. It is those involvements-to-come that will shape the course of the new century.

Indeed, by the turn of the twenty-first century the United States military had already appropriated the entire earth, and was ready to flood the most obscure areas of it with troops at a moments notice.

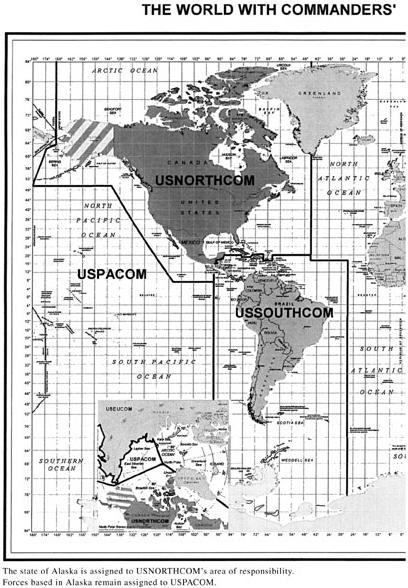

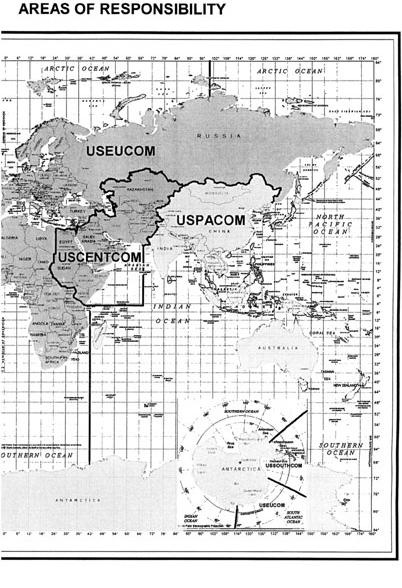

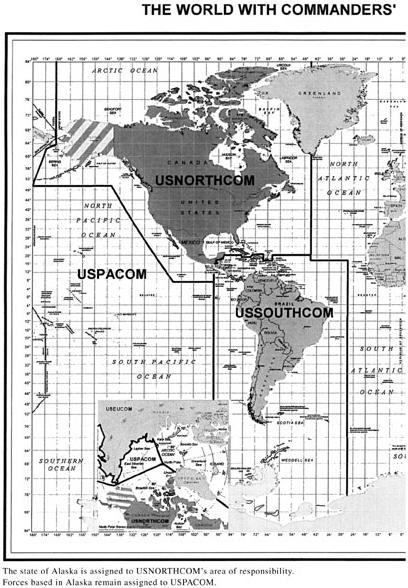

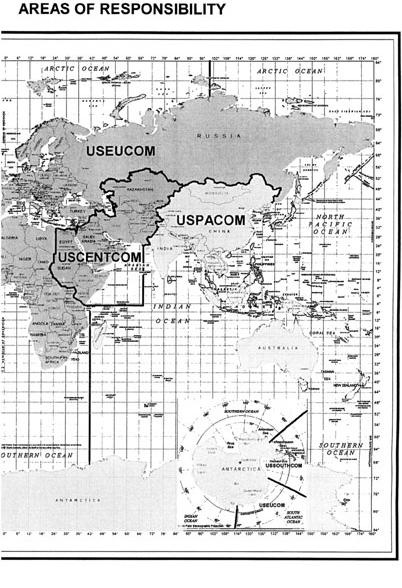

The Pentagon divided the planet into five area commandssimilar to the way that the Indian Country of the American West had been divided in the mid-nineteenth century by the U.S. Army. Instead of the military departments of Texas, New Mexico, Utah, California, Oregon, and the West, now there was Northern Command, or NORTHCOM; Southern Command, or SOUTHCOM; European Command, or EUCOM; Central Command, or CENTCOM; and Pacific Command, or PACOM.1 For example, at the corner of 5 degrees latitude and 68 degrees longitude, in the middle of the Indian Ocean, CENTCOM gave way to PACOM, just as EUCOM gave way to CENTCOM at the Turkish-Iranian border.

This map bore uncanny resemblance to one drawn in 1931 for the German military by Professor Karl Haushofer, a leading father of Geopolitik. The United States, having vanquished Germanys budding world empire in World War II, now had operational requirements for maintaining its own.

But according to the soldiers and marines I met on the ground in the far-flung corners of the earth, the comparison with the nineteenth century was more apt. Welcome to Injun Country was the refrain I heard from troops from Colombia to the Philippines, including Afghanistan and Iraq. To be sure, the problem for the American military was less fundamentalism than anarchy. The War on Terrorism was really about taming the frontier. But the fascination with Indian Country was never meant as a slight against Native North Americans. Rather, the reverse. The fact that radio call signs often employed Indian names was but one indication of the troops reverence for them.

This map left no point of the earths surface unaccounted for. Were I standing at the North Pole, where all the lines of longitude meet, I might have had one foot in NORTHCOM and the other in PACOM; or in EUCOM if I shifted a leg. After I first saw this map in the Pentagon, I stared at it for days on and off, transfixed. How could the U.S. not constitute a global military empire? I thought.

The only way to explore such a mapto know it intimatelywas on foot, or in a Humvee, with the troops themselves, for even as elites in New York and Washington debated imperialism in grand, historical terms, individual marines, soldiers, airmen, and sailorsall the cultural repositories of Americas unique experience with freedomwere interpreting policy on their own, on the ground, in dozens upon dozens of countries every week, oblivious to such faraway discussions.

This was true of both officers and enlisted men, for while generals were involved at the tactical level as never before, the actions of the lowliest corporals and privates could be of great strategic impact under the spotlight of the global media.2 It was their stories I wanted to tell: from the ground up, at the point of contact.

Truly, the increasingly decentralized nature of commandnecessary in a complex world where, for instance, each region of Afghanistan required a different approach to the local militiawas giving enlisted men unprecedented decision-making powers. Such responsibility required a firm, moral belief system, of which secular patriotism could form but a part. Thus I was interested in religion, and once on base went to as many religious services as I could.

I was less concerned with war and conquest than with imperial maintenance on the ground, and seeking a rule book for its application. The project would take years. I had the earth to roam. It could not be the work of one book but of several.

Here is the first.

But before I recount my odyssey through the barracks and outposts of the American Empire, I must address the issue of imperialism itself, a word with which most are uncomfortable, and about which there has been much recent debate.

Imperialism is but a form of isolationism, in which the demand for absolute, undefiled security at home leads one to conquer the world, and in the process to become subject to all the worlds anxieties.3 That is why empires arise at the fringes of consciousness, half in denial. By the time an imperial reality becomes truly manifest, it is a sign that the apex of empire is at hand, with a gradual retreat more likely than fresh conquests.