Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

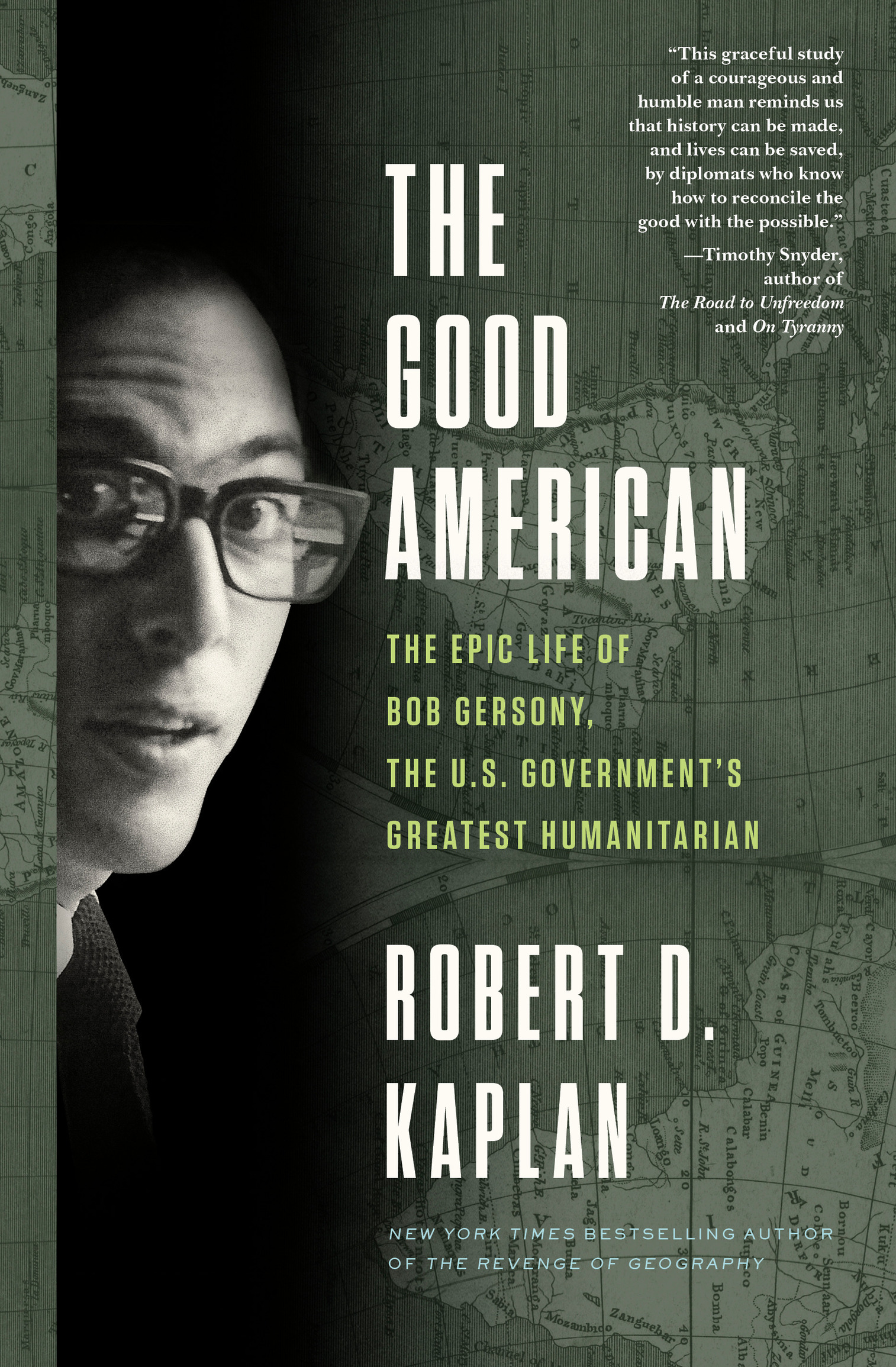

Copyright 2021 by Robert D. Kaplan

Maps copyright 2021 by David Lindroth Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Kaplan, Robert D., author.

Title: The good American / Robert D. Kaplan.

Description: New York : Random House, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2020012098 (print) | LCCN 2020012099 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525512301 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525512325 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Gersony, Robert. | United States. Agency for International DevelopmentOfficials and employeesBiography. | United States. Department of StateOfficials and employeesBiography. | Humanitarian assistance, American. | Refuge (Humanitarian assistance)United States. | PhilanthropistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC HC60 .K3435 2021 (print) | LCC HC60 (ebook) | DDC 327.730092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012098

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020012099

Ebook ISBN9780525512325

randomhousebooks.com

Cover design: Lucas Heinrich

Cover photograph: courtesy of the author

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

Contents

pessimismcan drive men on to do wonders.

V. S. Naipaul, A Bend in the River, 1979

Glory is now a discredited word, and it will be difficult to re-establish it. It has been spoilt by a too close association with military grandeur; it has been confused with fame and ambition. But true glory is a private and discreet virtue, and is only fully realized in solitariness.

Graham Greene (quoting Herbert Read), Ways of Escape, 1980

PROLOGUE

Mozambique

February 1988

She was a displaced farmer from Chemba, near to the border of Sofala and Tete provinces, in central Mozambique. Her village was at the intersection of the great Zambezi River and one of its tributaries. She spoke to him through a translator in Sena, a Bantu language of the Mozambique, Malawi, and Zimbabwe border areas. He had found her wearing a black kerchief and blue blouse. She appeared as quite self-possessed, crouching on the dirt floor of the hut, and beckoning him to sit beside her on a chair. The government troops of FRELIMO had fled her village, she explained to him, and RENAMO soldiers closed in from several directions, forcing the villagers to the bank of the Zambezi. FRELIMO, the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique, had come to power as an anti-Portuguese guerrilla group, with some support from Cuba and the Soviet Union. But it couldnt control the countryside where RENAMO, an indigenous African, anti-communist insurgency supported by apartheid South Africa, was on the rampage. RENAMO soldiers executed her niece, and soon afterward her nieces nursing daughter died of hunger and exposure. The woman told him she saw half a dozen bodies up close: of two young boys and other women and children. There were more bodies still, but she didnt have the courage to look at them. The woman and her own seven-year-old daughter then began to run but were chased into the big river by more RENAMO troops who had just arrived and were shooting at them, spraying the waters surface with bullets. People drowned, trying to escape the barrage.

She told him that she tried as best she could, but exhausted, made the split-second choice to save herself and in a panic let go of her daughter, who was swept away by the current and drowned. She said that God helped me to an island in the river, where people from Mutarara, on the far side of the river, came with boats to evacuate them. She remained in Mutarara as a displaced person for five months. But then RENAMO attacked it and she fled again, helped by the cover provided by the outnumbered FRELIMO troops. She then walked roughly twenty miles north to a refugee camp across the border in Malawi. She remained at Makokwe camp in southern Malawi for three months. But there was no future there, she told him. So she crossed the border back into Mozambique, where she stayed in a transit camp by a railway yard in Moatize, which was mortared by RENAMO. Then she escaped to a displaced persons camp in Benga, in Changara district, west of Moatize. She had been in Benga four months when he interviewed her on Monday, February 29, 1988, the third person he had interviewed there, according to his diary.

He remembered each person he interviewed by a distinguishing characteristic that he marked down in his notes. That way he could remember them as individuals, and thus preserve their humanity. This interviewee was the woman with the black kerchief.

The various expressions on her face, and the way she pronounced the words, were powerful and full of emotion. The moment she told me of letting go of her seven-year-old daughters hand in the great River, her hand slowly waved in the air, as if she were letting go again, and again.

He had no children of his own yet, though he was already forty-three. But he was torn apart by the image of the womans decision between surviving herself and letting her own daughter drown. He never got used to the stories he heard.

She was the 143rd of 196 refugees and displaced persons of the Mozambique civil war he interviewed, traveling between camps that were separated by hundreds of miles in war zones in Malawi, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Mozambique itself. He was eating one meal a day, interviewing people like her during all the daylight hours, concentrating hard so as never to ask a leading question. He lived out of a tent with a sleeping bag and mosquito coil, writing in his lined notebook and typing by candlelight as there was no electricity, remembering each voice through his fingertips.

It was merely another day of work for him, just another assignment, like all the others in war and disaster areas of the developing world: assignments which continuedliterally one after anotherfor four decades, on several continents. He was often lonely, depressed, but lived in fear of being promoted out of what he was doing. He was truly calm only while interviewing and taking notes. It was in such moments that he attained the quality of an ascetic, inhaling the evidence almost. For him, listening to these voices was like slow breathing. So he never stopped doing it.

The surroundings meant little to him. In his mind, the towering and interminable bush of Mozambique had been reduced to the lined pages of his notebooks, where his swift, graceful jottings became a sacred script: all he was able to remember were the stories that these refugees and displaced persons had told him.

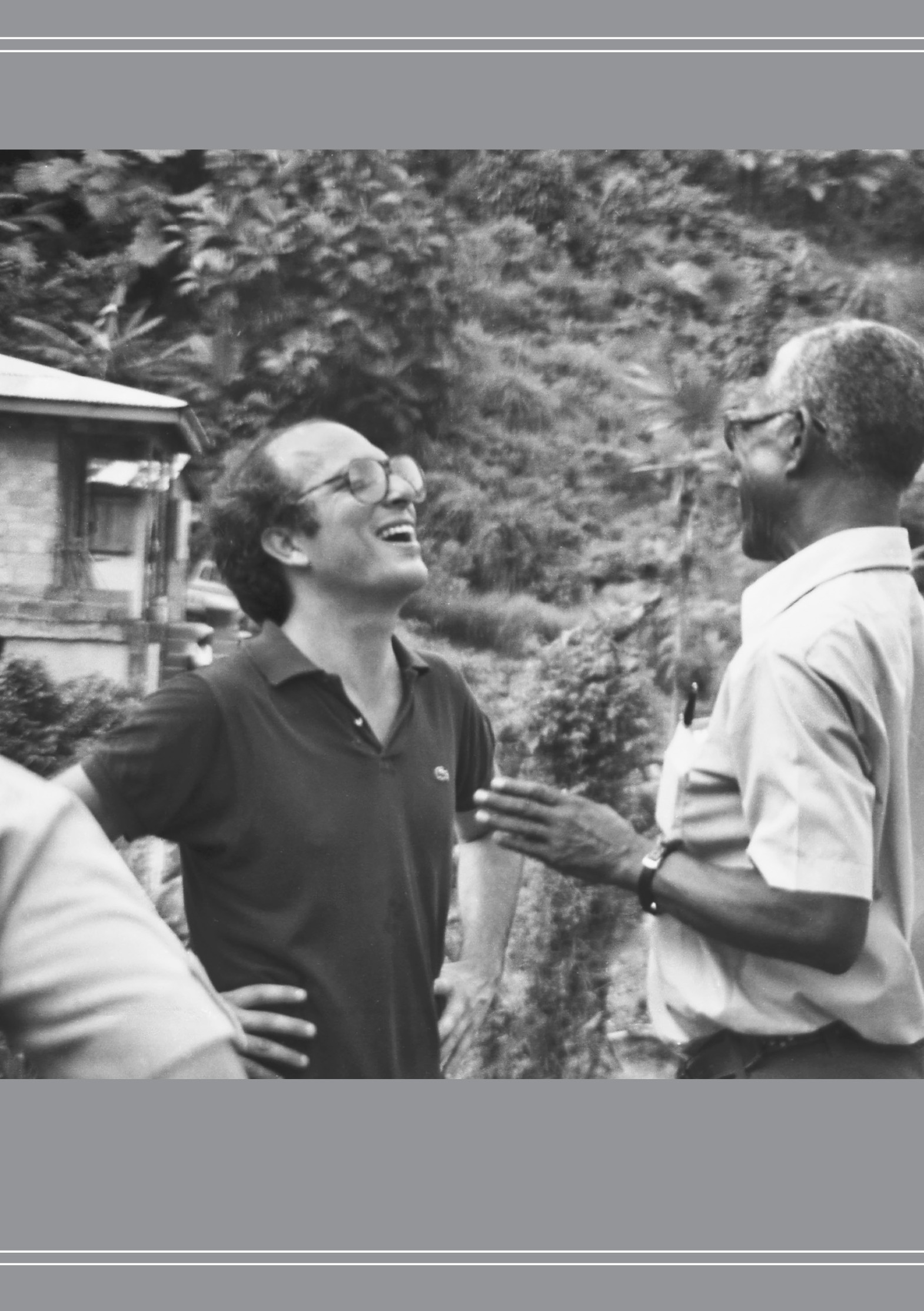

He was not a journalist or a relief worker. He worked for the U.S. government in a very unusual capacity. He deliberately avoided publicity, and thus many of those who flock to war zones barely knew he existed. In any case, as someone who was at heart an introvert, he was easily ignored by them. They made legends out of other people, not out of him.

I first met him in a cheap hostel in Khartoum more than a third of a century ago as I write these words, and crossed paths with him over the decades in Somalia, Liberia, Ethiopia, the Sudan-Chad border, Nepal, and other places. He was everywhere the news was, and also where it wasnt. Yet in a certain sense he was invisible, and he was happy that way.