I

EARNING THE ROCKIES

I f I dont remember my fathers name, who will?

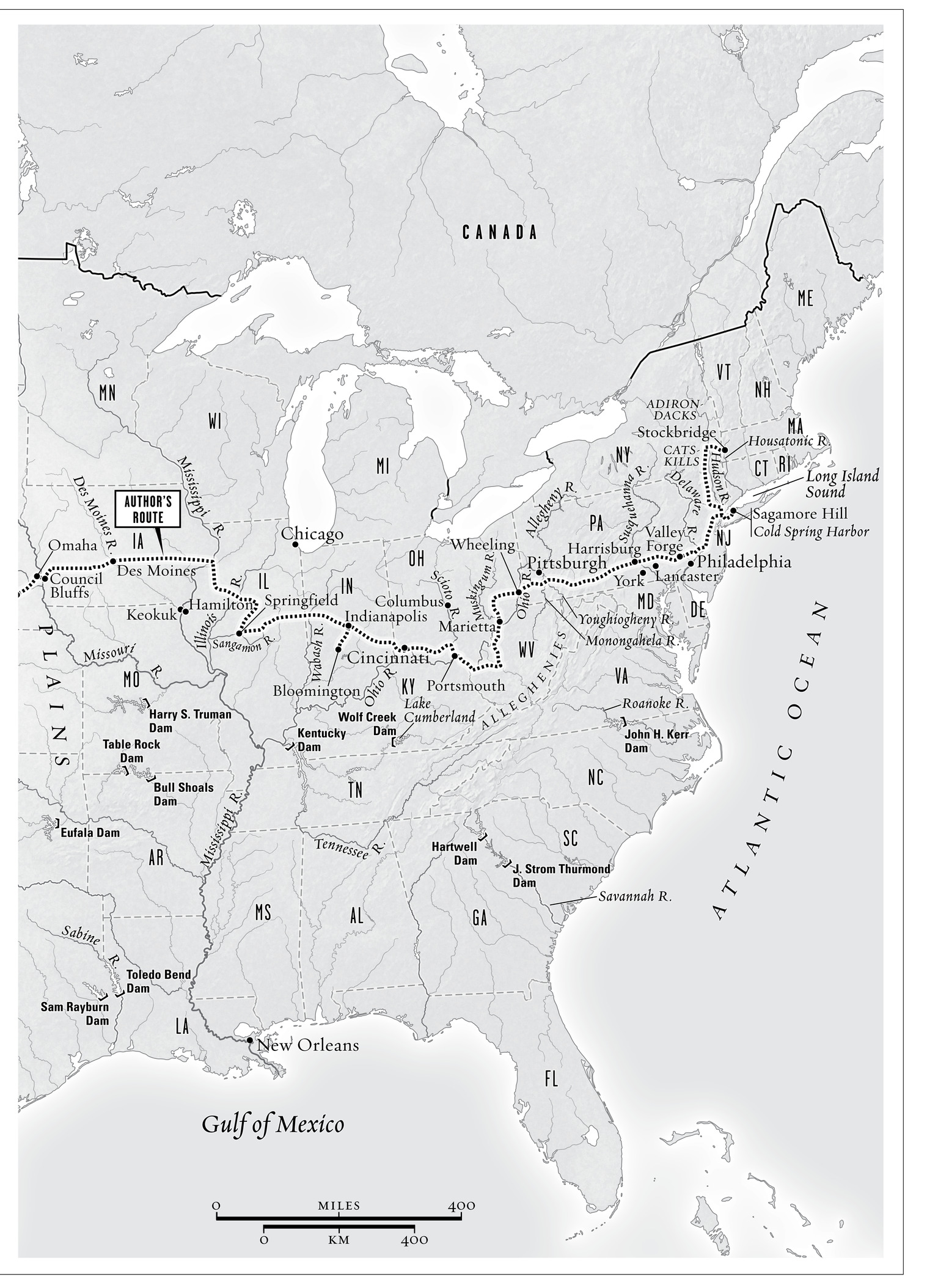

My fathers name was Philip Alexander Kaplan. He was born in Brooklyn in 1909. I dont recall him ever at peace with his life. I do remember him looking serene once at Valley Forge, among the oaks and maples and magnolias; clustered among the numerous birches and pine trees; and a second time among other hardwoods at Fredericksburg. These are trees I could not name when I was young but learned to identify on later visits to those hallowed sites, and to other sites on the Eastern Seaboard that the memory of my father inspired me to see. For it was only at such places, away from our immediate surroundings, that my father became real to me, and real to himself.

In particular, I remember him at Wheatland, James Buchanans handsome Federal-style home with the air of a southern plantation in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. There I peeked my chin over the protective barriers into sumptuous mid-nineteenth-century rooms, with their dark walnut desks and other antique furniture, along with the French china, glittering crystal, and gilded mirrors. Yes, I remember a grand piano there and many shadowy bookcases and lithographs. For long spans of my childhood my memory is vague, but it lights up with minute detail about what matters most to me. Wheatland, where President Buchanan lived, worked, headquartered his campaign for high office, and died, really mattered to me as a child. I was only nine, but my father in those rare moments spoke to me almost as though I were an adult, even as he was so full of tenderness.

My father laid out the fundamentals of Buchanans failure as president, perhaps the worst in our history: a story necessarily simplified for a nine-year-old. Of course, later in life I would fill in most of the details.

Whatever the multitude of factors in the three-way election of 1856, James Buchanan was by no means an accidental president. When he assumed office in March 1857, he appeared to have everything going for him. Arguably, no man in the country was better qualified for the task of calming the festering North-South split over slavery. He was a tall, reasonably wealthy, self-made, and imposing figure, someone who, aside from being a bachelor, was truly good at life: a former congressman, senator, minister to Russia in the Andrew Jackson administration, secretary of state in the James K. Polk administration, and minister to Great Britain in the Franklin Pierce administration; a talented and accomplished operator, a man of maneuver gifted at the fine art of compromise despite his stubbornness. He knew what buttons to push, in other words. Who else was possessed of the political savvy necessary to save the Union? Few were shrewder. Except for one thing, as it would turn out: Buchanan did not have a compass point toward which to navigate in the midst of all the deals he tried to make, and he had a distinct and fatal sympathy for the South. But mostly he was all ambition and technique without direction. Moreover, he was a literalist. He had a small vision of the Constitution and the frontier nation: he did not believe he and the federal government had the right to dictate terms to the southern states. He saw the good in both the pro-slavery and anti-slavery points of view. With his legalistic flair, he might have made a very competent president in more ordinary times; he was a disaster in extraordinary times. The country finally came apart under his watch. It turned out, he just,