To all our students and colleagues of The Math Circle

Contents

Chapter One

A Glimpse Inside

When I walked into the Harvard classroom, about eight students were already there, as Id expected. But people passing by were surprised to see themnot because there was anything unusual in early arrivals at the beginning of a semester but because of what these students looked like: sitting in their tablet armchairs, their little legs sticking straight out in front of them. They were all about five years old.

This was the first class for these new members of The Math Circle. The parents, ranged at the back, may have been nervous, but their children werent, because it was simply the next thing to happen in a still unpredictable life.

Hello, I said. Are there numbers between numbers?

I dont know what youre talking about, said Dora, in the front row.

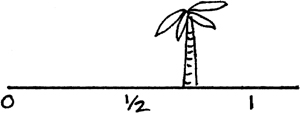

Ohwell, youre rightIm not too sure myself. I drew a long line on the blackboard and put a 0 at one end, a 1 near the other. Is there anything in there?

Sam jumped up and down. No, theres nothing there at all, he exclaimed, except of course for one half. This wasnt as surprising a remark as you might think, since Sam had just turned an important five and a half.

Right, I said, and made a mark very close to the 0 and carefully labeled it 1/2.

It doesnt go there! said Sonya, sitting next to Dora.

Really? Why not?

It goes in the middle.

Why?

Because thats what one half means!

I erased my mark and, with a show of reluctance, moved 1/2 to the middle, acting now as no more than Sonyas secretary.

Well, I said, is there anything else in there?

Silence five seconds of silence, which in a classroom can seem like five minutes. Ten seconds. Tom, at the back, got up and began to put on his jacket, because clearly the course was over: wed found all there was to find between 0 and 1.

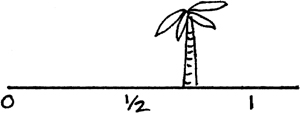

I guess its just a desert, I said at last, with maybe a camel or a palm tree or two, and began sketching in a palm tree on the number line.

Now thats ridiculous! said Dora, there cant be any palm trees there!

Why not?

Because it isnt that sort of thing! This is an insight many a philosopher has struggled over.

Obediently I began erasing my palm tree, when I felt a hand grabbing the chalk from mine. It was Eric, who hadnt said anything up to this point. He started making marks all over the number linemost of them between 0 and 1 but a fair number beyond each.

There are kazillions of numbers in here! he shouted.

Is kazillion a number? Sonya askedand we were fully launched.

In the course of the semesters ten one-hour classes, these children invented fractions (and their own notation for them), figured out how to compare themas well as adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing them; and with a few leading questions from me, turned them into decimals. In the next-to-last class they discovered that the decimal form of a fraction always repeatsand in the last class of all came up with a decimal that had no fractional equivalent, since the way they made it guaranteed that it wouldnt repeat (0.12345678910111213 ).

The conversations involved everyone, even a parent or two, who had to be restrained. Boasting and put-downs were quickly turned aside (this wasnt that sort of thing), and an intense and delightful back-and-forth took their place.

A sample: after they had found all sorts of fractions in the second class (most but not all with numerator 1), and located them (often incorrectly) on the number line where they thought they should be, I began the third class by saying I was troubled by having 1/3 to the left of 1/4 (in that part of the desert between 0 and 1/2), as they had wanted.

You may be right, I said, but I need convincing. A long debate followed, which divided the class into those who would (for no very good reason other than reading my doubt) put 1/4 before 1/3, and those who argued for leaving things as they stood, on the grounds that since 4 was greater than 3, 1/4 had to be greater than 1/3.

At the start of the next class, Anne put up her hand. Would I please draw two pies on the board? I groaned inwardly: she must have had a conversation with her parents during the week; but I drew two large, equal circles for her.

Now make the Mercedes sign in one in one and a cross in the other, she said. I did. We contemplated the drawingsthe message seemed clear. But Anne wasnt finished.

There, you see? If its a pie you like, a third is bigger than a fourth! But if its rhubarb, then a fourth is more than a third! This wasnt an argument I had encountered before.

You probably think this was a class of young geniuses, hand-picked for special training. In fact it was like any other Math Circle class: we take whoever comesmath lovers and math loathers; we dont advertise but rely on word of mouth. True, this is in the Boston area, with its high percentage of academic and professional families, but weve had the same sort of classes with inner-city kids, suburban teenagers, college students, and retireesfrom coast to coast, in London and Edinburgh, and (in German!) in Zurich and Berlin. The human potential for devising math, with pleasure, is as great as it is for creative play with ones native language: because mathematics is our other native language.

We came up with the idea of having such sessions one warm September evening in 1994, while having dinner with our friend Toms. The academic year was beginning, and what had long been bothering each of us inevitably came up: how could the teaching of math be in such bad shapeespecially in a city known for mathematical research? All that our students, whether college freshmen or ninth graders, knew about math was that they had to take it and that they hated it.

We had chicken with cream and complaints, but the chocolate mousse that followed was too light for such gloom, and one of us said: Why dont we simply start some classes ourselves?

Toms thought he could rent the basement of a nearby church on Saturday mornings. We wrote up a list of friends with children and telephoned around: Were going to have some informal conversations about math this Saturday morning. Would your children be interested?

One of those wed spoken to had heard of Nina Goldmakher in Brookline, who ran a Russian literary circle for children, and called her up. She was wonderfully enthusiastic and sent all of her students to us. We began that first morning with twenty-nine teenagers.

Word spread. We outgrew the church basement by the end of the semester, and Professor Andrei Zelevinsky, at Northeastern University, offered us free rooms there. Parents of younger and younger students called us up; Professor Daniel Goroff at Harvard found rooms for them on weekdays. To keep classes small, we trained graduate students as teachers. We incorporated as a nonprofit in 1996, still rely only on word of mouth, averaging 120 students each semester, meeting in twelve different sections. Weve kept the style informal, the bureaucracy minimaland couldnt have more fun.

Next page