Also by Robert D. Kaplan

ORIGINAL PREFACE

B efore moving to Greece in 1982, I bought several books about modern Greek politics, all but one of which were balanced, objective, and devoid of any emotion. They left me unmoved, and now are useful only as reference books to check a date or the spelling of a name. One of the books, however, was passionate, opinionated, and far more subjective than the others. The book, Greece Without Columns by the late British journalist David Holden, was a debunking of modern Greece as the birthplace of Western civilization. Although the book was pilloried by philhellenes, in a strange way I found it pro-Greek. It did something that none of the other, dull, predictable tomes did: it fired my imagination and made me want to know more, not less, about Greece. The following pages attempt to do the same for the Horn of Africa.

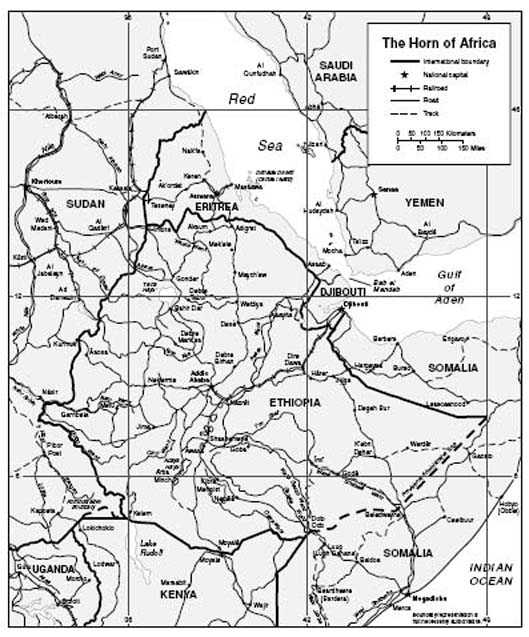

I had no intention of writing a dispassionate rehash of yesterday's headlines. Famine in the Horn is both a tool and an aspect of ethnic conflict, with the Ethiopian Amharas of the central highlands pitted against the Eritreans and Tigreans of the north. The overwhelming majority of U.S. journalists have reported on Ethiopia from one side onlythat of the Amharas in Addis Ababa. I wanted to show the story from the other side, in order to redress a grievous imbalance in news coverage. If the reader finds this book polemical, be advised that I meant it that way. To get people excited, you sometimes have to light a fire, and that was my intention.

This book covers the period from late 1984 to the early part of 1987. In late 1987, the famine returned, mainly for the very reasons cited inside. The section on the media is not exhaustive. I'm sure that there were both good and bad examples of reporting that escaped my attention. However, I seriously doubt whether they would have affected the overall thrust of coverage in the 19841987 period.

A journalist often does little more than articulate the concepts of others. Countless diplomats, government officials, and relief workers in Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Uganda, North Yemen, and Washington, D.C., provoked my interest with what they had to say. A few, however, did more: they helped me to think about Africa and the famine in a bold, unpopular, but more realistic way, judging Africa by the same standards of moral conduct that would apply to any other part of the globe. Because many of these analysts and diplomats are in sensitive, official positions, it is better that they go unnamed. They all have one thing in common, however: they know Africa from personal experience, not from artificial notions constructed from thousands of miles away.

The title of this book is taken from a Western diplomat's remarks to Robert J. Rosenthal of The Philadelphia Inquirer. Sections of the book appeared as works in progress in a number of publications. I therefore wish to thank editors at The Atlantic, The New Republic, The Wall Street Journal, and The American Spectator for their encouragement. The impetus for the book arose out of reporting trips to the Horn, financed by the radio division of ABC News, The Atlantic, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, and The Toronto Globe and Mail. A grant from the Institute for Educational Affairs of Washington, D.C., enabled me to take a year off in order to write and research the book. Whatever merit there is on the following pages is partly due to all these organizations.

Robert D. Kaplan

Athens, Greece

Spring 1988

FOREWORD

S urrender or Starve, my first book, also formed the basis for my first articles in The Atlantic Monthly, a magazine with which I have been associated for nearly two decades. The manuscript was completed in the summer of 1987 and published by Westview Press in the fall of 1988, before going out of print in 1994. Though it is a story of the Horn of Africa during the Cold War, it is relevant for understanding the region today, especially in light of the War on Terror. At the end of 2002, I returned to the Horn in order to write a postscript for the original manuscript.

In the mid 1980s, when I reported on and traveled in Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia, a famine of biblical proportions engulfed the region. The world media attributed the famine exclusively to droughtan act of God, for which Africans bore no responsibility: thus they were only victims. My realization that the famine was partly a factor of ethnic and class conflict, deliberately perpetrated by a Marxist Ethiopian government, much like the famine that Stalin had inflicted on the Ukraine in the 1930s, impelled me to write this book. In the 1980s, the nineteenth-century Ethiopian empire of the Amharas was cracking up, and the Amhara regime, fortified by Marxist ideology, was using famine as a means to pressure the rebellious Tigreans and Eritreans into submission. These divisions have still not been healed. Between 1998 and 2000, Ethiopia and Eritrea fought a full-scale war in which hundreds of thousands of people were displaced and tens of thousands killed. Tensions persist up through the present; as does the threat, yet again, of massive starvation.

Sudan, meanwhile, was undergoing its own rebellions in the mid 1980s, with southern Christians pitted against northern Moslems, much like today. The famine there was also not merely the result of drought: it was partly a consequence of the neglect with which the Arabs of Khartoum treated the non-Arab and non-Moslem parts of that vast country.

These issuesand the Cold War background to themhave recently been magnified in importance. U.S. military bases in Saudi Arabia have been under increasing restrictions, and in any case may not have a bright future. Therefore, the United States will have increasing need of bases and basing rights in countries close to the Middle East, especially in light of the large numbers of al-Qaeda terrorists in Yemen, directly across the Bab al Mandeb Strait from the Horn of Africa.

Not only have the U.S. Marines and Army Special Forces set up a basing platform in Djibouti, but the U.S. military may at some point extend its presence to neighboring Eritrea, whose friendly regime and port facilities at Massawa and Assab could make it strategically useful in the War on Terror for years to come.