Copyright 2017 Lee Berger. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 12,000 research, exploration, and preservation projects around the world. National Geographic Partners distributes a portion of the funds it receives from your purchase to National Geographic Society to support programs including the conservation of animals and their habitats.

Become a member of National Geographic and activate your benefits today at natgeo.com/jointoday.

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

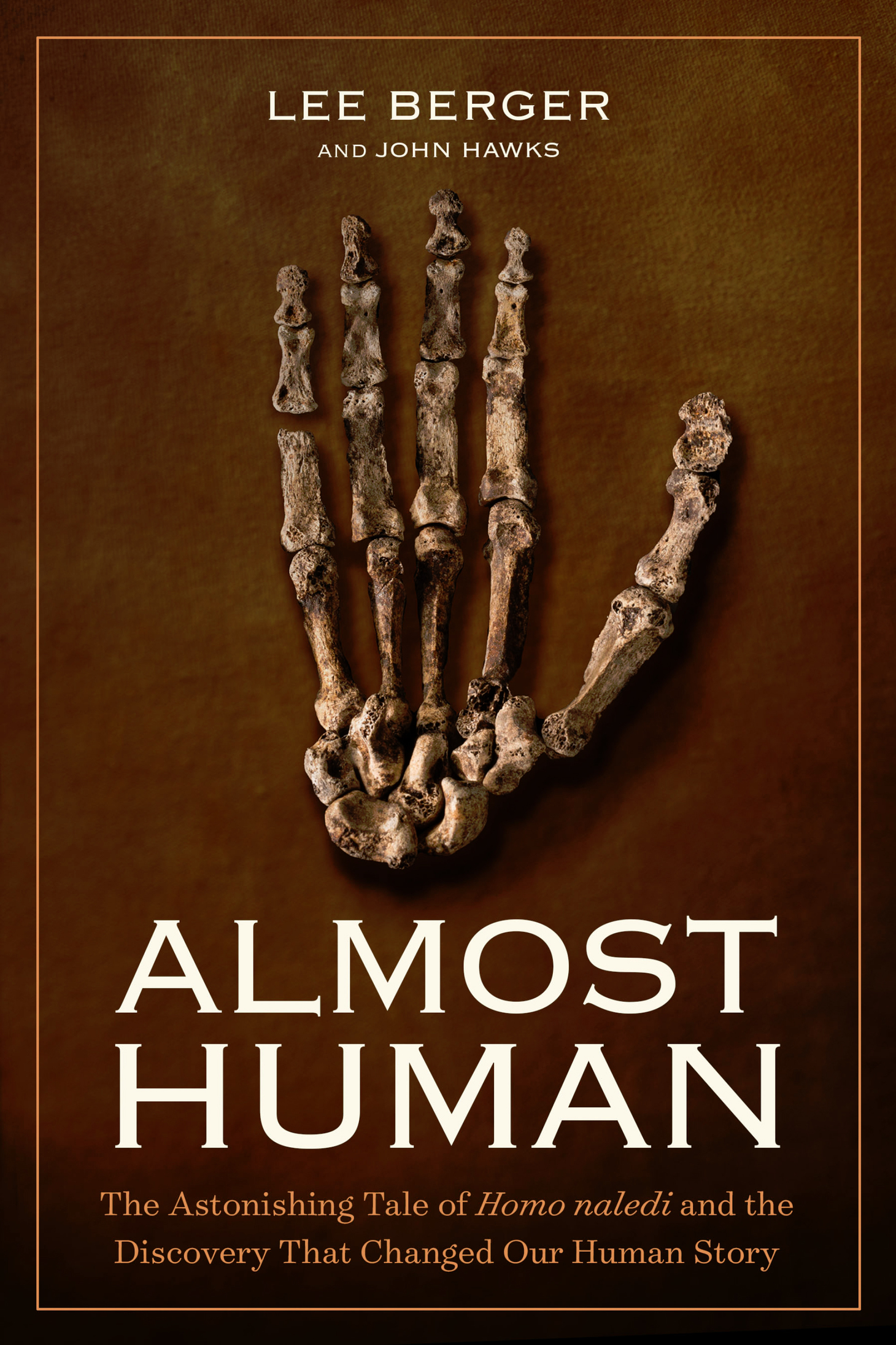

PROLOGUE

S lipping between the loose, rusty wires of the game fence, I paused to let my son, Matthew, through. I pressed my foot down on the lowest wire, pushing just hard enough to create a gap for Matt and my young Rhodesian ridgeback, Tau. Id barely made much of a space before they darted through.

With me on the other side was Job Kibii, a slim, Kenyan paleoanthropology postdoctoral student; we both smiled at our companions youthful energy. I pulled the wires wider for Job, and we turned toward a small cluster of wild olives and white stinkwood trees. Matt and Tau were already in the trees shade, a few dozen meters away.

Thats it, I said, gesturing toward the ring of trees. I cant believe I didnt find it earlier.

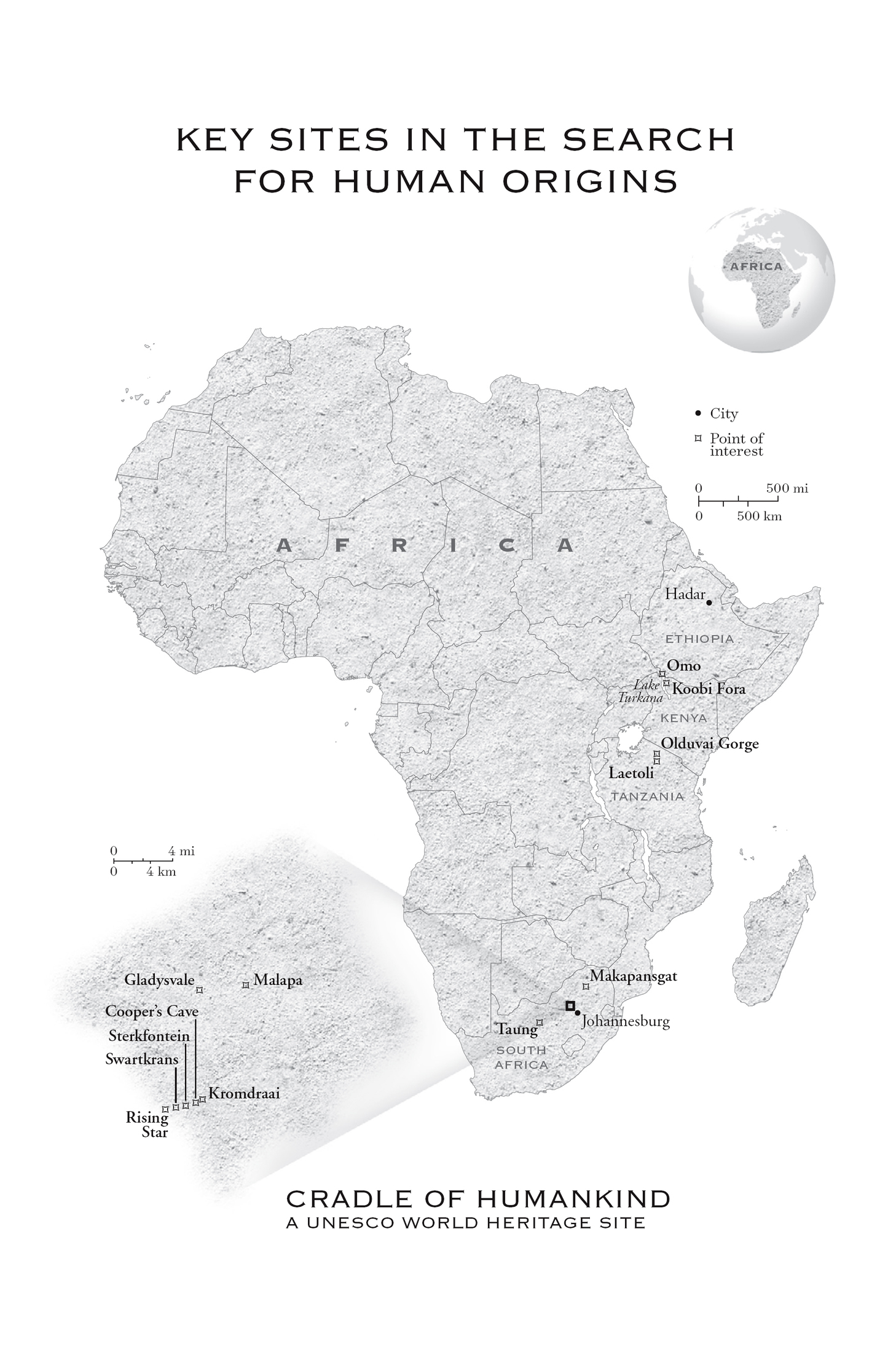

Job nodded in agreement as he surveyed the rolling landscape of the Cradle of Humankind. The Cradle, a large area designated by UNESCO as a World Heritage site, is not far from my home in Johannesburg, South Africa. Just a few dozen kilometers outside a metropolis of more than five million people, this place is a world away: a pristine wilderness, home to zebras, antelopes, giraffeseven leopards and hyenas. It is also one of the most famous areas for fossil discovery on the planet. Most of that fame was established during a golden age of paleoanthropology, from the mid-1930s up to the 1970s, when scientists discovered caves full of fossil bone deposits going back three million years.

I had known this area for 18 years; for the past several months, I had been conducting a new survey of fossil sites here. It was the morning of August 15, 2008a typical winter morning on the Highveld: crisp, cool, and cloudless. I had no idea that in just a few minutes, my life was going to change forever, thanks to a discovery made by a boy and a dog.

I WAS WORKING TO confirm a hunch, originating with a 10-year-old computer error that had set me in motion a few months before. The previous December, I had started surveying this terrain I knew so well with Google Earth, the new satellite imageviewing software. Of course, the first thing I looked at was my house (where, thank goodness, the satellite hadnt caught me lounging by the pool). Then I checked the sites I already knew. Google Earth was new, but I had been surveying the Cradle using handheld global positioning system (GPS) units since 1998. I could practically recite the lat-long positions for fossil sites from memory.

I started with Gladysvale, a cave situated nearly in the center of the Cradle where I had first worked in 1991 and where I had found two hominin teeth. Homininsalso called hominidsare members of the human family tree, which includes all the extinct species more closely related to people than to any great apes living today. Hominin bones are precious pieces of evidence for our origins.

I had expected we would find more hidden treasures among the tons of rock and sediment we excavated during the next decade and a half of exploration at Gladysvale. But in the long run, although my colleagues, students, and I found the remains of thousands upon thousands of antelopes, we found only fragments of one or two hominins. Still, I loved the place, loved the feeling of being in the bush. I had even loved looking at every one of those antelope bones, even if they werent from hominins.

With Google Earth up on my computer screen, I punched in Gladysvales GPS coordinates. I remember seeing the satellite image leap upward from my house, way up into the sky, swing northwest, and then rapidly zoom down onto the Cradle. I could see the familiar hills, streams, and valleys around Gladysvale becoming sharper and sharper. But as the image blurred to huge pixels, I saw there was something wrong. This wasnt Gladysvale: It was actually the valley next to Gladysvalea spot almost 300 meters away! I typed in the coordinates of another place I had worked, the Coopers Cave site. Again, the image leaped into the air, this time moving southwest. Again, the position was wrong. I entered location after location, and none was correct. I was horrified. Had I recorded the GPS coordinates incorrectly? Had I been working with the wrong numbers for almost a decade?

I soon learned that in the 1990s, before GPS was perfected for public use, the handheld units were primitive and somewhat error-pronein part because they were designed for military use, with deliberate error built in to confound potential enemies. It meant that to use Google Earth to view all those sites I knewmore than 130 altogetherI had to relocate their positions manually.

That left me trawling the landscape on the computer screen. At first I felt frustratedyears of work had to be correctedbut slowly I began to recognize that this mistake was leading me to a new way of looking at things. I began to understand what caves and fossil sites really looked like from overhead. Some were marked by clusters of trees, some by disturbances in the ground. Sometimes they were clustered, often in linear patterns that I realized must mark the geological faults that had allowed caves to form. Slowly the prospect emerged that the Cradle of Humankind might contain more sites than anyone had previously thought: in the bedrock, underground.