Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

FOR JONATHAN

Jeepers, Creepers, whered ya get those peepers?

Jeepers, Creepers, whered ya get those eyes?

Johnny Mercer, 1938

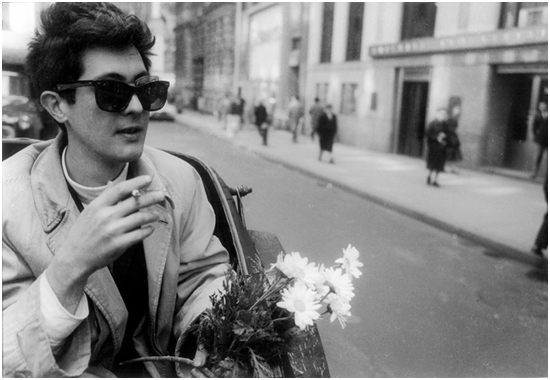

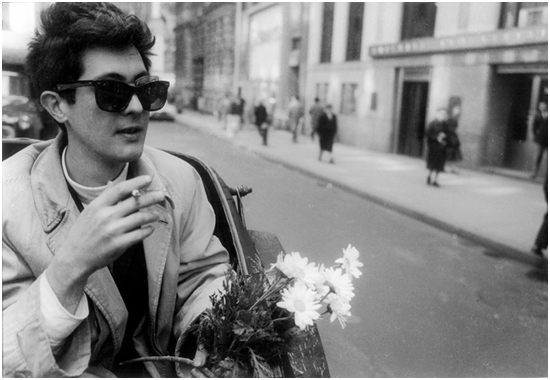

Richard (Dick) Bellamy was one of the most influential and enigmatic American art dealers of the sixties. The artists he was the first to championpop luminaries such as Claes Oldenburg and James Rosenquist, and minimalists such as Dan Flavin and Donald Juddare today shown in museums from Paris to Des Moines, Sydney to Dsseldorf. Their names are well known. Dicks isnt. I met Dick in 1986, when I was a curator at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. It was hard to believe that this charming, waifish man with frayed cuffs and eyeglasses mended with tape was the legendary art dealer Id heard about from artists. And I was fuzzy on the details. Most people were. Intrigued, I began to research Dicks career and discovered that there was almost nothing in print about him. I decided to remedy this, though the path forward was hardly clear.

The American art critic and philosopher Arthur Danto was particularly encouraging when I shared my intention to document Dicks accomplishments. But when Dick heard about it, he asked his friend Alfred Leslie to convey his discomfort at the prospect. Deferentially, I let go of the idea. Five years later, in 1995, Leslie himself urged me to reconsider, Dicks distress notwithstanding. Isnt there anything I can say to make you stop? Dick said without rancor when he phoned to dissuade me again. This time, I respectfully stood my ground, and he tacitly agreed not to put up roadblocks. By the time he died, in 1998, this biography was under way. As I trekked into Dicks past, interviewing hundreds of his contemporaries, I learned that there was more to him than met the eye, and it would require guile and resourcefulness to match the subject.

Dick ran the Green Gallery on Fifty-Seventh Street between 1960 and 1965 with the covert support of Robert and Ethel Scull, who became the countrys first celebrity art collectors. The remarkable talent he unearthed was jaw-dropping, but what really sustained my attention for what became a twenty-year journey was Dicks singular attitude toward money. He simply wasnt interested in making it, even as the market for contemporary art exploded all around him. A latter-day Bartleby, he preferred not to profit from the opportunity. The best art dealers have a fictional quality, the cartoonist Saul Steinberg once observed. Dick called to mind Sir Gawain, Huckleberry Finn, and Miniver Cheevy. He performed life with tragedy and farce as templates.

The puzzle pieces I gathered didnt all fit together at first. Some of his friends described his dark side; others thought him a bodhisattva or lay Jesuit. Gradually a picture of this extraordinary, contradictory man emerged, a picture, in Nabokovs words, the finder cannot unsee once it has been seen. In the end, I found Dick to most resemble Coyote, the culture-giving trickster in Native American mythologyeccentric, delightful, and gross, a shadowy figure with a capacity for intense pain and the rare gift of intuition.

Dick and Sheindi lived downtown on Cherry Street, a street on the way to nowhere. She remembered it from her childhood, when the fragrance of spices rode in on the breeze from the East River warehouses a few blocks away. Her Orthodox Jewish background was as foreign to Dick as the shape of his eyes and his shock of black hair were to her. Shed been charmed by his voice, a resonant baritone mellowed by smoke and alcohol. A onetime radio announcer, Dick read aloud all his beloved writers, especially Wallace Stevens. The lover writes, the believer hears, / The poet mumbles and the painter sees, / Each one, his fated eccentricity / living in change. He might teasingly append and the art dealer droolingly sells.

He could make a game out of anything. Dick-foolery, his friends called it. On the evening of October 20, 1959, he helped Sheindi on with her coat with the politesse of a medieval knight. They were heading to the grand opening of the Guggenheim Museum, a black-tie affair. No one there would be dressed as Sheindi was. A thrift shop maven, like all her friends, Sheindi had found a handkerchief-silk sheath in rich autumnal colors that needed only a few repairs. She teamed it with a white slip Dick had bought for her in Chinatown, now light brown after a dip in tea. At a distance, the otherwise demure Hebrew school teacher seemed to be wearing nothing underneath.

Dick and Sheindi were getting by on her salary and the little he made from odd jobs. Hed been director of the artists cooperative Hansa Gallery until it folded in May. He had more time now to visit studios and the new, seat-of-the-pants galleries downtown. He dreamed of a gallery of his own, a place to show the art he found that baffled and unsettled him. At thirty-one, Dick was a man with few possessionsa seemingly humble figure, never taking nor being taken. He was like the Fool in a deck of Tarot cards, signifying change and new beginnings, life existing to be enjoyed.

* * *

Robert and Ethel Scull lived in Kings Point, Great Neck, Long Island, in a house Robert built for her on Blue Sea Lane. It overlooked a small cove on Manhasset Bay, as if nature had nibbled a recess in the coastline just for them. On the afternoon of the Guggenheim gala,

Ethel took her time deciding what to wearshe had such wonderful options. She appreciated the way a pink Balenciaga cocktail dress rose playfully at the front and trailed to the back, and she loved the fluidity and grace of a lace strapless designed by Yves Saint Laurent. Her closets were full of haute couture purchased abroad, all the more prized because she had paid no duty on her return. Before she left her Paris hotel, she delicately removed the French designers labels and stitched in American ones.

With his share of his father-in-laws taxi business, Bob had built a thriving cab company. In the past few years he and Ethel had begun to buy artRenaissance bronzesuntil prices turned dear. They moved on to art of their own time, newcomers such as Jasper Johns, and the abstract expressionists Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko. But not Jackson Pollock. The market for Pollock, who had died in a car crash in 1956, already outpaced them. Growing the collection with safe investments required more money than they had or were willing to pay. It was getting too expensive to buy artists vetted before they became aware of them.

* * *

As the Sculls chauffeured Cadillac pulled up in front of the Guggenheim, the No. 6 train jolted to a halt at Eighty-Sixth Street and Lexington Avenue. Dick and Sheindi stepped off and strolled toward Central Park. They turned uptown at Fifth, the dark expanse of the park on their left. Like the Cheshire cat, the museum materialized all at once, disembodied bands of light set against the night sky. Frank Lloyd Wrights design seemed an exhilarating preview of what the future would look like. New Yorkers hadnt been so eager to experience an interior space since the early thirties, when Radio City Music Hall opened the largest indoor theater in the world. Unlike the Museum of Modern Arts modernist box, which slid into place beside Gilded Age brownstones, the Guggenheim sat back on its lot like an imperious turbaned pasha.