IMAGES

of Aviation

MARINE AIR GROUP 25

AND SCAT

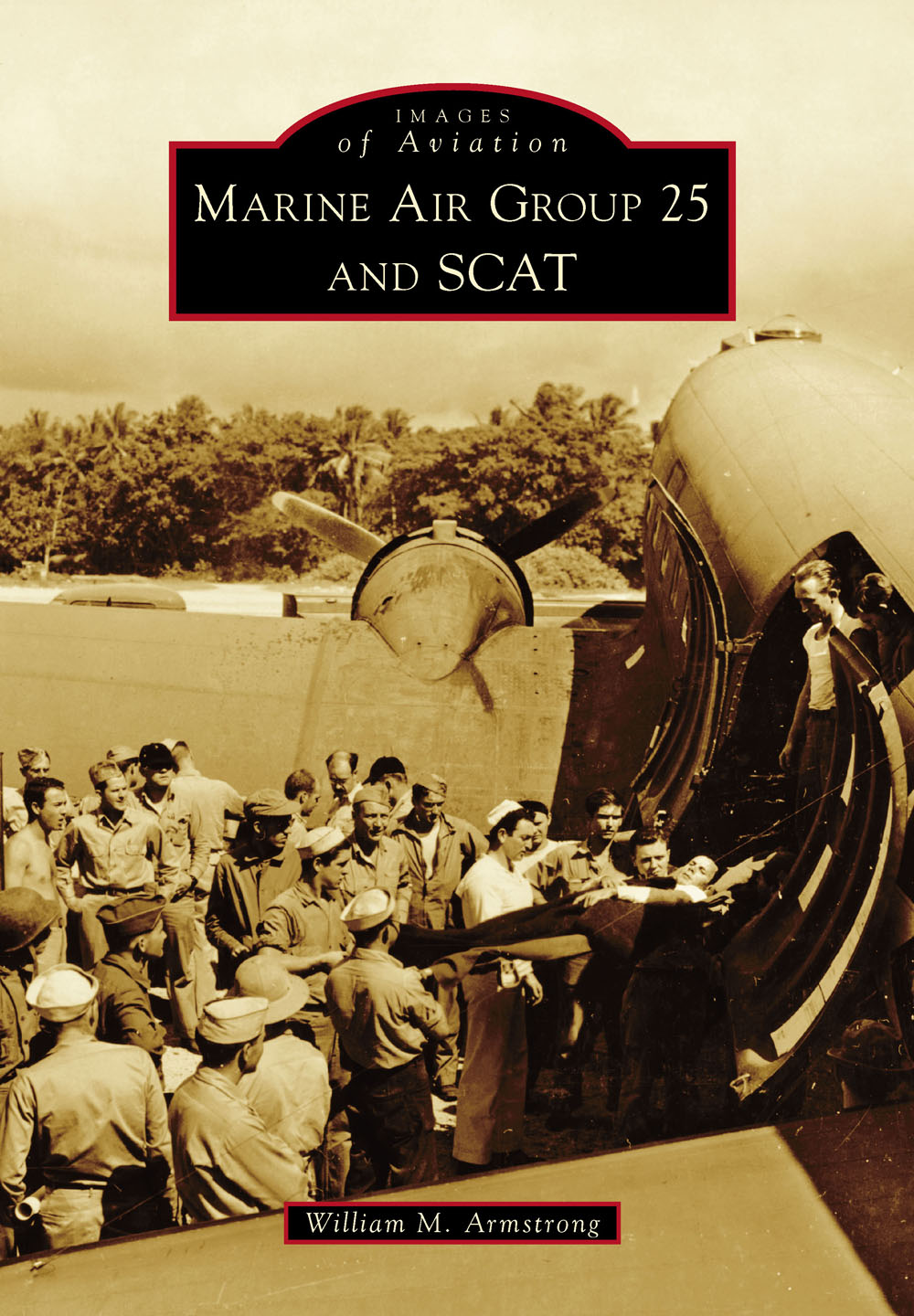

During World War II, there was a logistics unit whose name and reputation were known by nearly everyone throughout the South Pacific: SCAT. SOPAC (South Pacific) Combat Air Transport Command, with Marine Air Group 25 as its core, was an outstanding joint-service transport unit operating across the vast theater in support of frontline units. These SCAT R4D aircraft were photographed by famed photojournalist David Douglas Duncan in New Caledonia. (National Archives and Records Administration.)

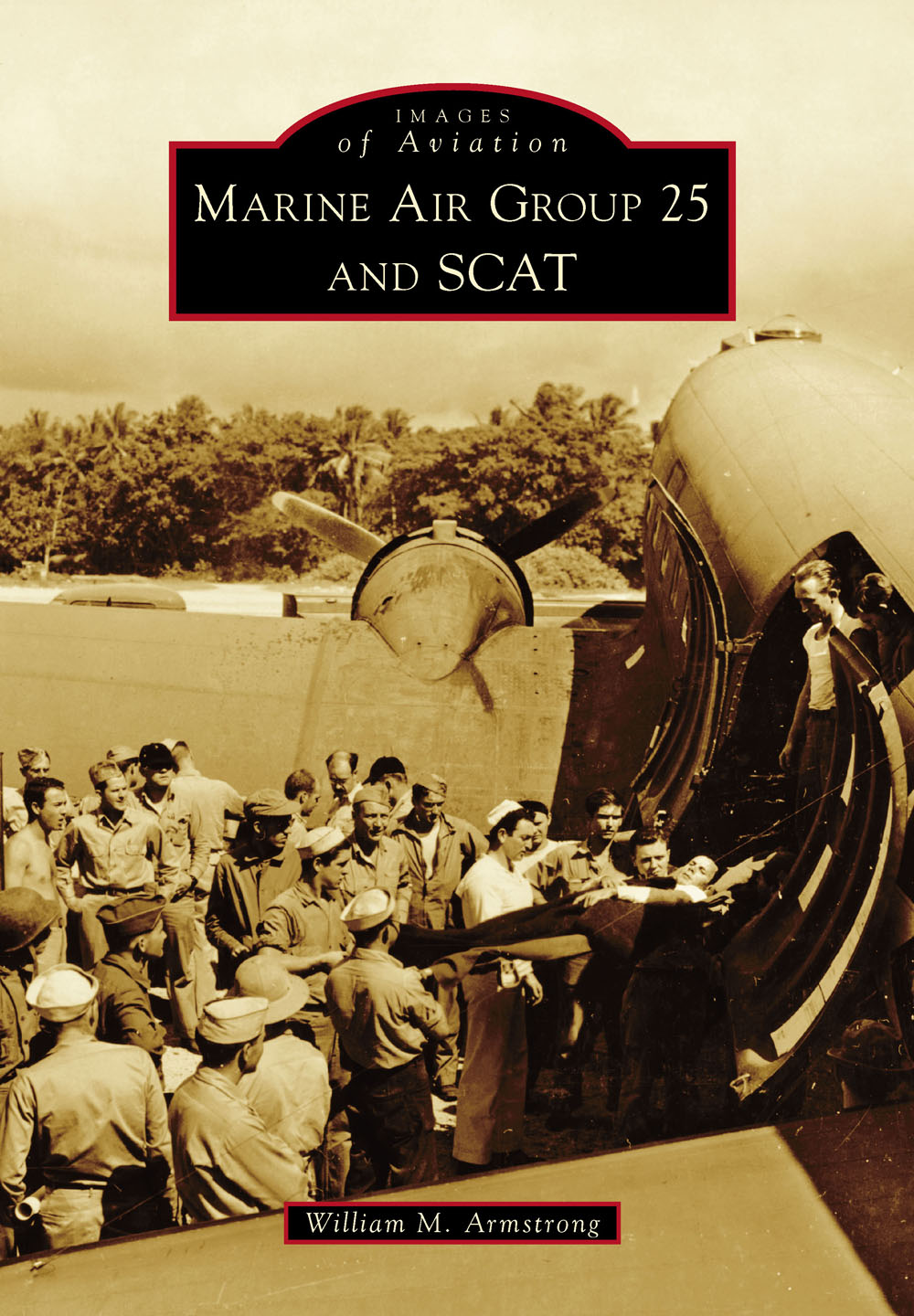

ON THE COVER: Crowding around a SCAT R4D from Marine Air Group 25, medical personnel receive casualties from Guadalcanal at a hospital in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) in the South Pacific. The aircrafts crew, charged with overseeing the unloading process, stand by ready to assist. Out of all of its important missions SCAT was best known for aeromedical evacuation. (National Archives and Records Administration.)

IMAGES

of Aviation

MARINE AIR GROUP 25

AND SCAT

William M. Armstrong

Copyright 2017 by William M. Armstrong

ISBN 978-1-4671-2743-1

Ebook ISBN 9781439663332

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017939676

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

For Joshua, Riley, and Elizabeth, and in loving memory

of Capt. William E. and Virginia DuRoss.

Dedicated to the veterans of MAG-25 and SCAT.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to begin by thanking the members of Marine Air Group 25 and SCAT Veterans of World War II, especially Dr. H. Jesse Walker, Bob Stitt, John Diehl, Stan Bieber, Paul Hookie Wynn, Roland La Forest, Dick Haven, John Duboise, Leland Blackwell, and Cliff Arthur. My wife and I would like to give special thanks to our friends Harold Klesath and Anita Young, whose company was the highlight of every reunion that we attended. My first reunion experience would not have been possible without the kind guidance of Bud Wegener, Bill Sears, Oliver Jones, Art Noe, and Grant Parks. My friend Ted Schwartz has spent decades preserving and promoting MAG-25s legacy, including the collection and digitization of the units newspaper, the Ton-Tooter. Although I never met him, I am heavily indebted to Robert Biggane, who steered the organization for decades and preserved valuable photographs and other records.

No individual did more to inspire this book than my late grandfather, Bill DuRoss, who indulged my childhood fascination with the air war in the South Pacific, although he seldom spoke of his own experiences. As always, my wife, Elizabeth, has helped at every stage of the books development, offering valuable insights and guidance. Our children, Riley and Joshua, have been extraordinarily patient as I spent countless hours on yet another project involving old pictures. I hope that this book will have a special meaning for them as the great-grandchildren of a MAG-25 veteran.

I would also like to thank Holly Reed and the staff of the Still Pictures Branch of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), College Park, Maryland, who have been facilitating my periodic searches for MAG-25 and SCAT photographs for over 15 years, and Sylvester Jackson and Maranda Gilmore at the Air Force Historical Research Agency (AFHRA), Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama. Additional photographs come from the Naval History and Heritage Command (NHHC) and the archives of the former Marine Air Group 25 and SCAT Veterans of World War II Inc. (MAG-25/SCAT). Photographs from the authors collection, except where noted, come from the family albums of William and Virginia DuRoss.

INTRODUCTION

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, inadequate combat airlift capability can be counted among the many ways in which the United States was unprepared for war. Although the war in Europe had led to a renewed interest in air transport, and promising designs were in development, transport units and adequate transport aircraft were few and far between. The immediate solution was to mass-produce an adaptation of a popular and successful commercial airliner, the Douglas DC-3, for military service, and quickly train thousands of skilled men to fly and maintain them.

That process was well underway when the United States launched its first offensive against the Japanese Empire on the remote island of Guadalcanal (code name Cactus) in the Solomon Islands. There, the Japanese had begun construction of an air base that could threaten the approaches to Australia and New Zealand. The enemy proved tenacious, and supplies were short due to early Japanese dominance of the waters surrounding the island.

Back in the United States, a transport squadron had just been formed around a talented pool of experienced airline pilots, members of the Marine Corps Reserve. Their aircraft was the new Douglas R4D, although crews often still referred to it as the DC-3, or simply DC. Marine Utility Squadron 253 (VMJ-253) and its parent unit, newly established Marine Air Group 25 (MAG-25), received the urgent word to deploy to New Caledonia, a Free French enclave in the South Pacific, to support the Guadalcanal operation. Meanwhile, a veteran Marine squadron, VMJ-152, also prepared to deploy. It had recently exchanged its motley collection of utility aircraft for R4Ds. Although many of its wartime personnel were new to the Marine Corps, during the preceding decade the squadron had played a critical role in the development of Marine Corps air transport, and several key MAG-25 officers were veterans of the unit.

MAG-25, initially consisting of Headquarters Squadron 25 and the flight echelon of VMJ-253, arrived at Tontouta Air Base, New Caledonia, in September 1942, and almost immediately began flights to Guadalcanal. VMJ-152 was assigned to MAG-25 and arrived in New Caledonia in October 1942. That same month, a US Army Air Forces (USAAF) unit, the 13th Troop Carrier Squadron (TCS), was attached to MAG-25, kicking off an impressive feat of interservice cooperation. The USAAF, like the Marine Corps, had begun rapidly expanding its air transport capability with aid from experienced airline pilots. The 13th TCS had been activated in December 1940. In November 1942, Marine Service Squadron 25 (SMS-25) was activated to provide maintenance for the group.

On November 24, Commander, Aircraft, South Pacific Force (COMAIRSOPAC), Vice Adm. Aubrey Fitch, directed that this cooperative effort be organized under a new command, SOPAC Combat Air Transport Command (SCAT), operating under the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing. Throughout SCATs existence, it would be led by the senior officer of MAG-25 and would operate with a mix of US Marine Corps, Army, and Navy personnel.

The units of SCAT flew daily in support of Guadalcanal operations, at times proving vital to the success of air operations on the island. By the time of VMJ-253s first missions to the island, the Marines ashore had taken to calling the invasion Operation Shoestring, rather than the official Operation Watchtower, due to their lack of resources and the tenuous supply chain to the island. Guadalcanals defense against frequent Japanese air attacks fell largely to the ragtag Cactus Air Force, a heroic mix of overtaxed US Navy, Marine Corps, and USAAF units who struggled against the odds to keep their battered aircraft airworthy. Engineers fought a near-constant battle to keep the islands airstrips operational despite Japanese bombardment.

Next page