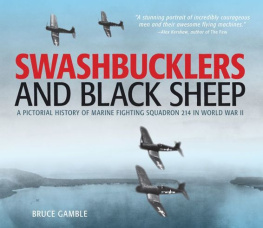

SWASHBUCKLERS

AND BLACK SHEEP

A PICTORIAL HISTORY OF MARINE FIGHTING SQUADRON 214 IN WORLD WAR II

BRUCE GAMBLE

To my mother, June Irvin Gamble:

Thank you for a lifetime of inspiration and encouragement

O ne of the tremendous highlights of my life has been an association with Marine Fighting Squadron 214 going back more than twenty years. My first contact was a meeting with John Bolt, one of Pappy Boyingtons original pilots, on behalf of the Naval Aviation Museum Foundation. I conducted a lengthy interview with John at his law office in 1991, and he got a big kick out of seeing his interview published in two consecutive issues of Foundation magazine. My reward was even better: John arranged for my family and me to join the rest of the surviving veterans in 1993 as they celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of their establishment. We spent an entire week with the Black Sheep in New Orleans, and in between the parties (Im still impressed by the quantities of booze they consumed), I was able to interview each of the attendees. Several brought their photograph albums and logbooks. A few months later, Frank Walton, the squadrons former intelligence officer, sent me five shipping cartons containing his collection of documents, tapes, war diaries, and photographs. Terminally ill, he passed away within weeks.

One of the most amazing discoveries in Waltons collection was a war diary passed to him by his predecessor. Its handwritten pages contained a day-by-day account of VMF-214 from the date of its commissioning until Boyingtons reorganization of the squadron in August 1943. Armed with the diarys copious details, I tracked down and interviewed the survivors of the pre-Boyington group, who called themselves the Swashbucklers. Later I did the same for the third iteration of VMF-214, which deployed aboard USS Franklin in 1945. The outcome was The Black Sheep, published in 1998, followed by Black Sheep One, a cradle-to-grave biography of Greg Boyington. Both books feature detailed narratives, but were limited by design to small galleries of black-and-white photographs. Thus, it has long been my intention to produce a companion work to showcase the photos and artwork Ive collected over the years.

Because the focus of this new work is visual, the accompanying text does not provide an exhaustive history of the squadron, nor is it intended to be scholarly, with chapter notes and other end matter. The narrative, while completely original, was drawn largely from my previous accounts; therefore, the bibliography is quite brief. Readers wishing to learn more about the pilots and their aerial actions, or about the complexities of Pappy Boyington, are encouraged to investigate The Black Sheep and Black Sheep One, which contain far more descriptive text.

While developing this project, I discovered some gaps in the photographic record of VMF-214. Numerous squadron members carried personal cameras during the war, but not many took pictures from the cockpit while flyingtheir duties were simply too demanding. Therefore, the collected photos mostly depict life on the ground or at sea. To provide some representation of fighter combat, I turned to several artist friends for help. Their interpretations add a beautiful dimension to the squadrons pictorial history. Readers will also find more than a dozen highly detailed profiles of the aircraft flown by VMF-214 and their Japanese adversaries during World War II.

Unlike my previous books, Swashbucklers and Black Sheep contains a photographic tribute to the squadrons postWorld War II service, including its role as an attack squadron. It is my sincere hope that readers feel a deep sense of appreciation for the sacrifices made by the Black Sheep, whose service to our country now spans more than seventy years.

I am grateful for the support and assistance of numerous individuals. The following provided technical expertise on Japanese units and aircraft: Rick Dunn, Jim Lansdale, Luca Ruffato, Henry Sakaida, Jim Sawruk, and Osaumu Tagaya. Help with historical details and photographs specific to VMF/VMA-214 was provided by Michael Bean, Charlie Boswell, Toby Bowers, Ted Carlson, Pete Dunbar, Theo Elbert, Hill Goodspeed, Kevin Gonzalez, Jeff Hill, Curt Lawson, Mint Moore III, Rafe Morrissey, Stan Peit, Barrett Tillman, and Gary Velasco. Most of the black-and-white photographs appearing herein were provided by the following veterans of VMF-214: John Bolt, Henry Bourgeois, George Britt, Vince Carpenter, Stan Free, Jim Hill, Ken Linder, Fred Losch, Mac McCall, Bob McClurg, Frank Walton, and O. K. Williams.

I am especially pleased to present the fine art of Craig Kodera, Jim Laurier, Bob Rasmussen, and John Shaw, as well as the digital artwork of Michael Claringbould and Tod Gunter. Thank you, gentlemen, for your beautiful enhancements to these pages.

I owe a very special thanks to the men and women of VMA-214, who hosted a reunion of original veterans and previous commanding officers at MCAS Yuma, Arizona, in April 2011. Several of them provided assistance with this project, including Capt. Charles Boy George, Lt. Col. Troy Frosi Roesti (MAG-13), Lt. Col. Robert Pat Schroder, and Capt. James Z Zafereo.

Lastly, I wish to thank Editorial Director Erik Gilg and acquisitions editor Scott Pearson for their professionalism and support in bringing this work to fruition.

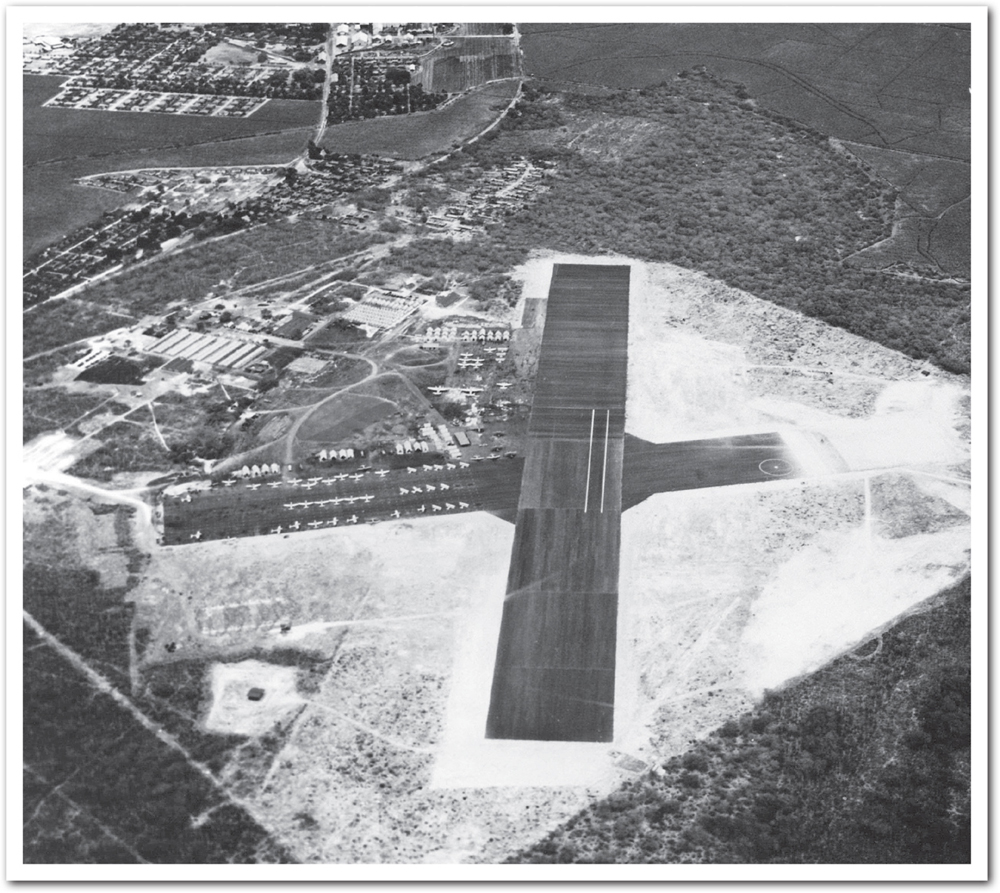

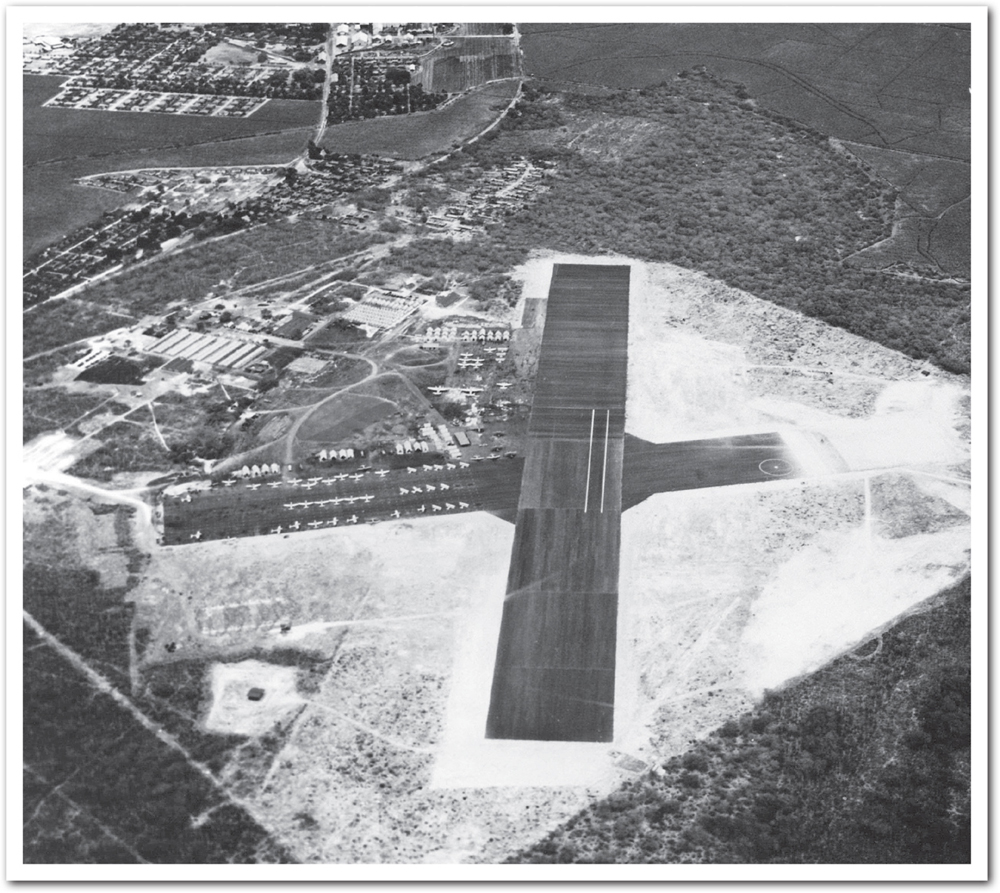

The birthplace of VMF-214: MCAS Ewa, Territory of Hawaii. Originally a mooring mast field for the giant U.S. Navy dirigibles of the 1930s, Ewa (pronounced eh-vah) was later turned over to the Marine Corps and developed into an air station for fixed wing aircraft. Note the biplanes in this prewar photograph. National Archives

T he aviation branch of the United States Marine Corps, created fully a century ago, was one of the smallest and most obscure components of the armed services at the beginning of World War II. On the eve of the Japanese attack against Pearl Harbor, the Marines had a mere seventy-one fighters in frontline serviceand ten of those went up in flames on December 7, 1941. The next day, seven of twelve Grumman Wildcats based on tiny Wake atoll were destroyed on the ground, and the remaining five were demolished within two weeks. A few months later at Midway, twenty-three Marine fighters were shot down or damaged beyond repair, with fifteen pilots killed. Compared with the stunning victory earned by the U.S. Navy on June 4, 1942, the Battle of Midway remains the worst single day of combat in the history of U.S. Marine aviation.

Next page