2017 by Susan Burton and Cari Lynn

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2017

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-213-7 (e-book)

CIP data is available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Minion Pro and Bembo

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

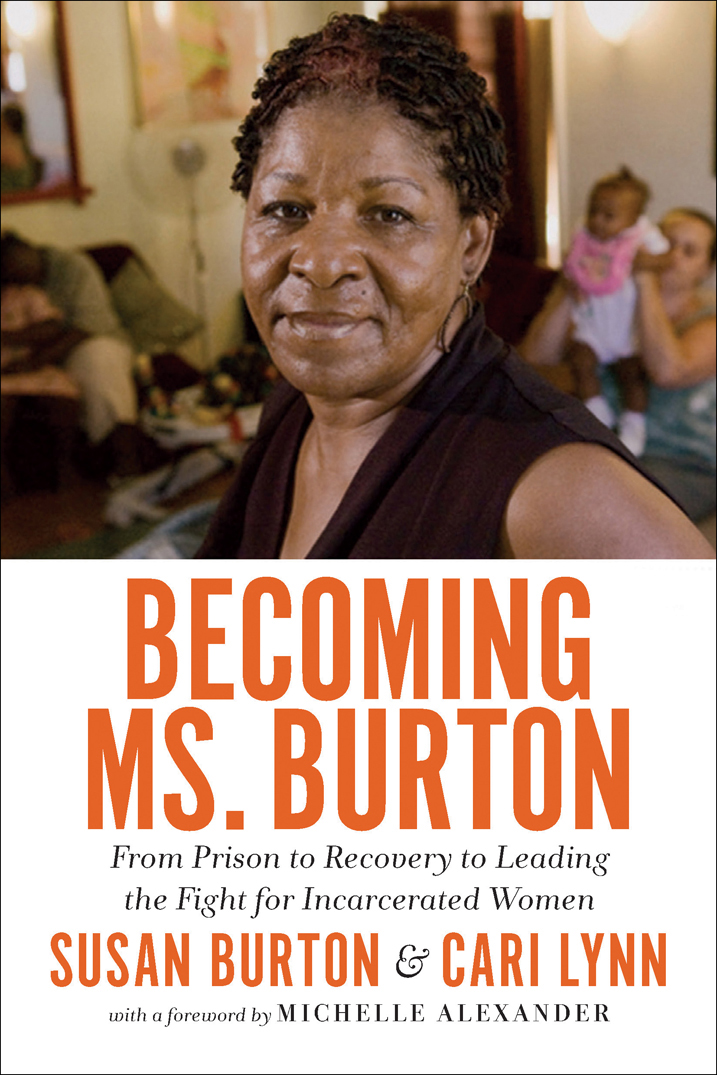

Most women in U.S. prisons were, first, victims.

Its estimated that 85 percent of locked-up women were, at some or

many points in their lives, physically or sexually abused, or both.

Disproportionately, these women are black and poor.

I was born and raised in those statistics. My life is now devoted to

stopping this cycle.

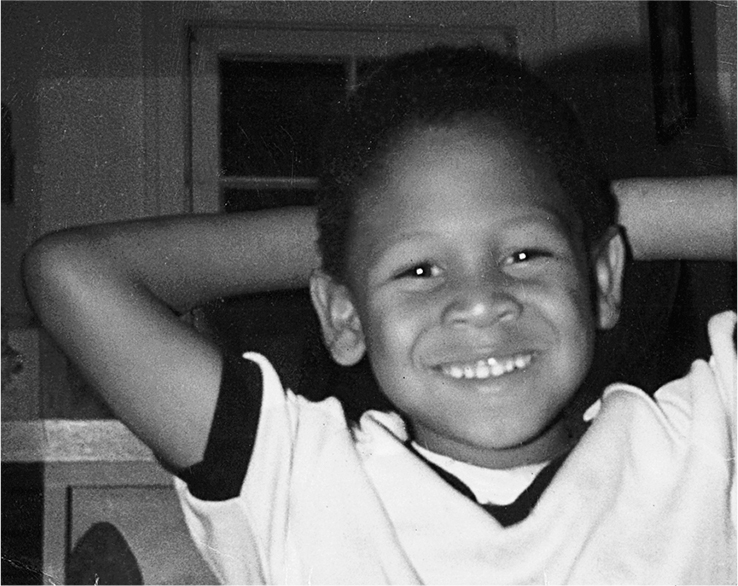

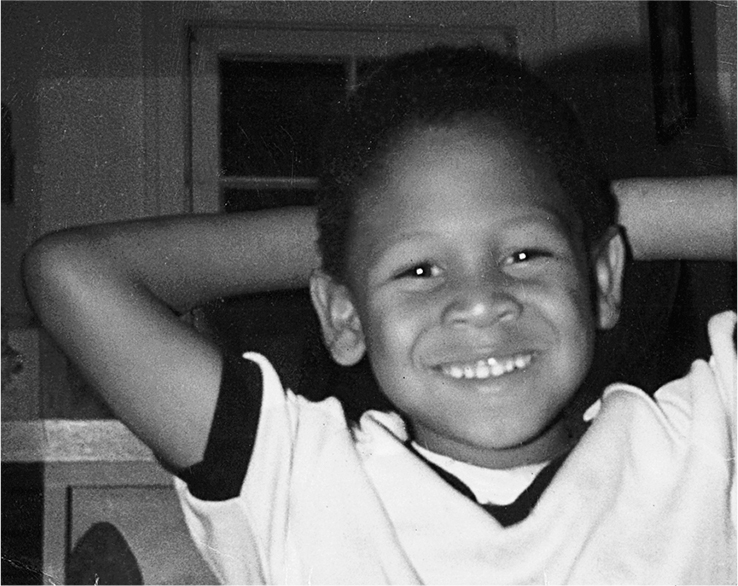

This book is dedicated to my son, K.K.

And to my daughter, Toni, and granddaughter, Ellesse.

And to all the women who may lie on their prison bed

dreaming of a new way of life.

A NOTE TO THE READER

T his book is drawn from my own life and experiences. It is also a book of memory and opinionand memory and opinion, as we all know, may have their own stories to tell. The names and identifying details of some individuals have been changed out of respect for their privacy; the first occurrence of a changed name is indicated in the notes for each chapter that appear at the end of the book. SB

CONTENTS

Table of Contents

Guide

T here once lived a woman with deep brown skin and black hair who freed people from bondage and ushered them to safety. She welcomed them to safe homes and offered food, shelter, and help reuniting with family and loved ones. She met them wherever they could be found and organized countless others to provide support and aid in various forms so they would not be recaptured and sent back to captivity. This courageous soul knew well the fear and desperation of each one who came to her, seeing in their eyes all the pain she felt years ago when she had been abused and shackled and finally began her own journey to freedom.

Deep in the night she cried out to God begging for strength, and when she woke she began her work all over again, opening doors, planning escape routes, and holding hands with mothers as they wept for children they hoped to see again. A relentless advocate for justice, this woman was a proud abolitionist and freedom fighter. She told the unadorned truth to whomever would listen and spent countless hours training and organizing others, determined to grow the movement. She served not only as a profound inspiration to those who knew her, but as a literal gateway to freedom for hundreds whose lives were changed forever by her heroism.

Some people know this woman by the name Harriet Tubman. I know her as Susan.

I met Susan Burton in 2010, but I had learned her name years before. I was doing research about the challenges of re-entry for people incarcerated due to our nations cruel and biased drug war. At the time, I was in the process of writing The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindnessa book that aimed to expose the ways the War on Drugs had not only decimated impoverished communities of color but had also helped to birth a new system of racial and social control eerily reminiscent of an era we supposedly left behind.

The United States has become the world leader in imprisonment, having quintupled our prison population in a few short decades through a drug war and get tough movement aimed at the poorest and darkest among us. I was writing a chapter that explains how tens of millions of people branded criminals and felons have been stripped of the very rights supposedly won in the civil rights movement, including the right to vote, the right to serve on juries, and the right to be free of legal discrimination in employment, housing, access to education, and public benefits. I had mountains of policy analyses and data, but was disturbed by the fact that few voices of those who had actually been impacted by these modern-day Jim Crow policies could be found in the research.

I scanned dozens of articles online, then paused when I stumbled upon an interview with a woman named Susan Burton. The integrity and authenticity of her voice were undeniable. She told the reporter plainly and directly what it felt like, as a recovering drug addict released from prison and struggling to survive, to be forced to check the box on the ubiquitous employment, housing, and food stamp applications that asked the dreaded question, have you ever been convicted of a felony? She knew full well that, once that box was checked, her application would be thrown straight in the trash. How would she survive without food, shelter, or a job? She described with clarity and conviction what it meant to be a second-class citizen in the so-called land of the free, and she insisted that she was determined to do everything she could to ensure that the laws, rules, policies, and practices that authorize legal discrimination against people with convictions are eventually abandoned, and that we begin to provide drug treatment rather than prison cells to people struggling with addiction and drug abuse. I learned Susan had created several safe homes for formerly incarcerated women and that she was part of a small but growing movement for the restoration of basic civil and human rights for people who have spent time behind bars. The interview moved me, and I thought, I have to meet this woman.

Shortly after The New Jim Crow was published, I had my chance. A mutual friend introduced us via email and Susan invited me to come to Los Angeles and visit the nonprofit organization she founded, A New Way of Life. She thanked me profusely for my book and said that she, along with the formerly incarcerated women currently residing at the safe homes, wanted to organize a book event for me at a local community center. I told her that I would be thrilled to come and hoped to learn more about her work and lend support as best I could.

I was not prepared for what followed. Upon my arrival, Susan gave me a tour of the safe homes for formerly incarcerated women that operate as part of A New Way of Life. Im not certain what I expected, but probably something similar to various halfway houses Ive seen over the years. Instead, I discovered something else entirely. These were not facilities or shelters or way stations or simply housing for people released from prison who need support services. These were homes. Loving homes. Susan took me from house to house and showed me where the women slept and worked. The residents and staff greeted Susan with a measure of formalityGood afternoon, Ms. Burton!yet the warmth and love were palpable. In some of the bedrooms, paint was peeling off the walls, and mattresses for children were on the floor along with a few scattered stuffed animals. Clearly, every penny raised was immediately invested in providing more beds, houses, and services. The accommodations were sparse, to say the least. But they were also immaculate, and every woman I met expressed enormous gratitude for Susan and the lifeline she provided. Susan offered not just a place to sleep and to get desperately needed assistance, but also emotional support as the women struggled to meet the seemingly endless and impossible requirements of parole and probation officers, as well as the demands of the most feared agency of them all: child protective services.