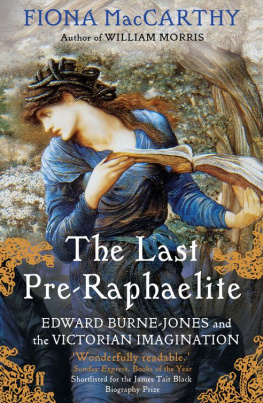

When Edward Burne-Jones died in 1898 a memorial service was held in Westminster Abbey, after special intervention from the Prince of Wales. The Abbey was packed and the sense of grief was genuine. This was the first time an English artist had been honoured in this way. The unworldly young recruit to the once derided Pre-Raphaelite movement had arrived at a unique position in late Victorian Britain: Sir Edward Burne-Jones, by now a baronet, had become an elder statesman of Victorian art. His driving force had always been a moral one; like his friend William Morris he was set against the age. But in many ways Burne-Jones had encapsulated it. He had become the licensed escapist of his period, perpetrating an art of ancient myths, magical landscapes, insistent sexual yearnings, that expressed deep psychological needs for his contemporaries. His paintings released forces half-hidden in the deep recesses of the Victorian imagination.

Burne-Jones had been a man of violent responses and antipathies who was apt to thrust a red-hot poker through a book he disapproved of, and he believed boldly in the power of art to counteract the spiritual degradation, the meanness and corruption he saw everywhere around him in the ruthlessly expansionist, imperialistic Britain of the nineteenth century. Crooked statesmen, unjust laws, rampant commercialisation. His visionary paintings offered an alternative scenario of the immaterial which for his admirers became realer than the real. What did Burne-Jones mean by beauty? This is what he said:

I mean by a picture a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be in a light better than any light that ever shone in a land no one can define or remember, only desire and the forms divinely beautiful.

Burne-Jones is a tantalising subject for biography partly because of his enormous productivity. He did just so much, in such different directions, with that very Victorian hyper-energy. As an artist Burne-Jones was extraordinarily versatile, working in a diversity of techniques and materials on many different scales. He resists any easy definition. Besides his large-scale paintings and whole sequences of pictures he made thousands of designs for stained glass, embroidery and tapestry, hand-painted furniture, clothes, shoes and jewellery. Loving music, Burne-Jones even started a campaign for the reform of piano design. In collaboration with William Morris he made numerous illustrations for books.

He never stopped designing. An evenings entertainment, after a hard day in the studio, would be the rapid drawing out of a cartoon for his latest stained-glass window, with his friends and his family gathered around. One of the problems for anybody trying to keep track of his chronology is his tendency to work on several assignments simultaneously. There was always a queue of projects in his mind. A painting begun in, say, 1869 might be abandoned for two decades then brought out again and finished in a frenzy of activity for an exhibition. Many works were never completed at all. Unpainted Masterpieces, one of the most brilliant of his self-caricatures , shows the artist in the studio overcome with shame, as a stack of blank canvases piles up in the background. Burne-Jones clients had to brace themselves for a long wait.

His character too can be maddeningly evasive. A peculiar doubleness pervades his personality. He was neurotic, depressive, prone to violent mood swings. The melancholy dreamer who seemed so withdrawn and solemn could suddenly become uproariously merry, whimsical and bantering with that particular Victorian style of silliness. His laugh, we are told in the memoirs of the period, was of the Ho-ho! kind. Visitors to his house would watch with fascination the sudden transformation of the mage into the conjuror at a childrens party, like meeting the impish eyes of Puck beneath the cowl of a monk. Burne-Jones was friends with many actors Henry Irving, Ellen Terry, Sarah Bernhardt and there was a strong element of staginess in him.

His charm was legendary. For one of his chief clients, the rising politician Arthur Balfour, Burne-Jones was simply the most charming man he ever met. People loved Burne-Jones for his intelligence and sweetness, his empathy and wit. But he was unpredictable. They knew they could not nail him. I want to reckon you up and its like counting clouds, John Ruskin once complained. Compared with Burne-Jones, his close friend William Morris whose life I wrote some years ago had been straightforward. Morriss personality had a grand consistency. Burne-Jones prevaricates and teases, tries to slip away.

So how to pin down a man with an innate resistance to biography ? Burne-Jones had himself thrown out the challenge I found quite irresistible: lives of men who dream are not lives to tell, are they? What is there to say about an artist or poet ever? My life is what I long for, and love, and regret, and desire, and no one knows on earth. I realised this was a book I had to take my time on. I allotted four years to it; it took me nearer six.

I felt it was a book that would need a lot of travel. One way to comprehend him was examining his places: Birmingham, the burgeoning industrial city that was Burne-Joness birthplace; Oxford where Burne-Jones was an undergraduate and where he first discovered his vocation as an artist; London and especially West Kensington where Burne-Joness house, The Grange, became so famous in its period as a beacon of Aesthetic Movement taste.

Most important was the tracing of his travels around Italy, a kind of artistic apprenticeship for him as he studied the great Italian artists of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. I followed the routes of his four journeys made in 1859, 1862, 1871 and 1873 to Venice and Florence and gradually south through Tuscany to Rome, seeing what he saw and recorded in his notebooks and his sketchbooks, gradually understanding the paintings and the buildings that gave him such high moments of excitement. Burne-Jones returned to England Italianised. From then on his art would be crucial in the forming of the English dream of Italy that still persists.

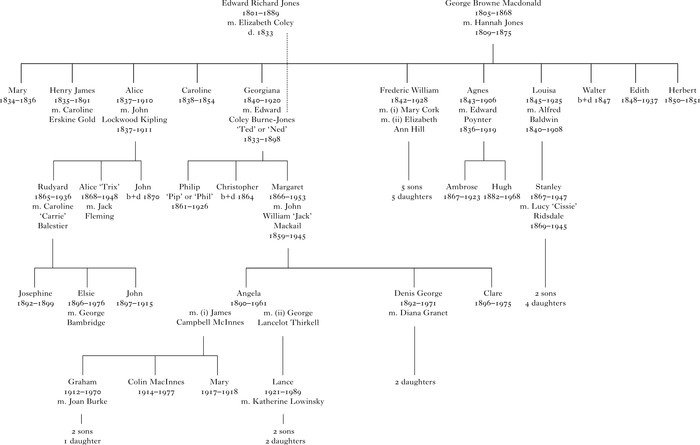

One of my intentions in writing this biography has been to bring Burne-Jones out from under William Morriss shadow. He is all too often seen as Morriss rather wimpish junior partner, an idea in which he himself colluded in his beautiful cartoons of the two of them together. This ridiculously simplifies the truth. They were of course close friends, in a friendship dating back to Oxford when they were undergraduates together. They were working partners in the decorating firm set up by William Morris, the enterprise that became the highly successful Morris & Co. But creatively Burne-Jones was more than Morriss equal. He was the greater artist although Morris was unarguably the greater man.

Socially they moved in rather different London circles, increasingly so as Burne-Jones was cultivated by the well-to-do intellectuals and aesthetes while Morris became a committed revolutionary Socialist. Having previously described the agonising rift that arose between them in the 1880s from Morriss viewpoint it was interesting to approach their political divergence from the other side. Burne-Jones remained convinced that an artists fundamental role within society lay not in political activism but in concentrating all his energies into producing works of art. This is a political debate that still continues. What precisely is an artist for?