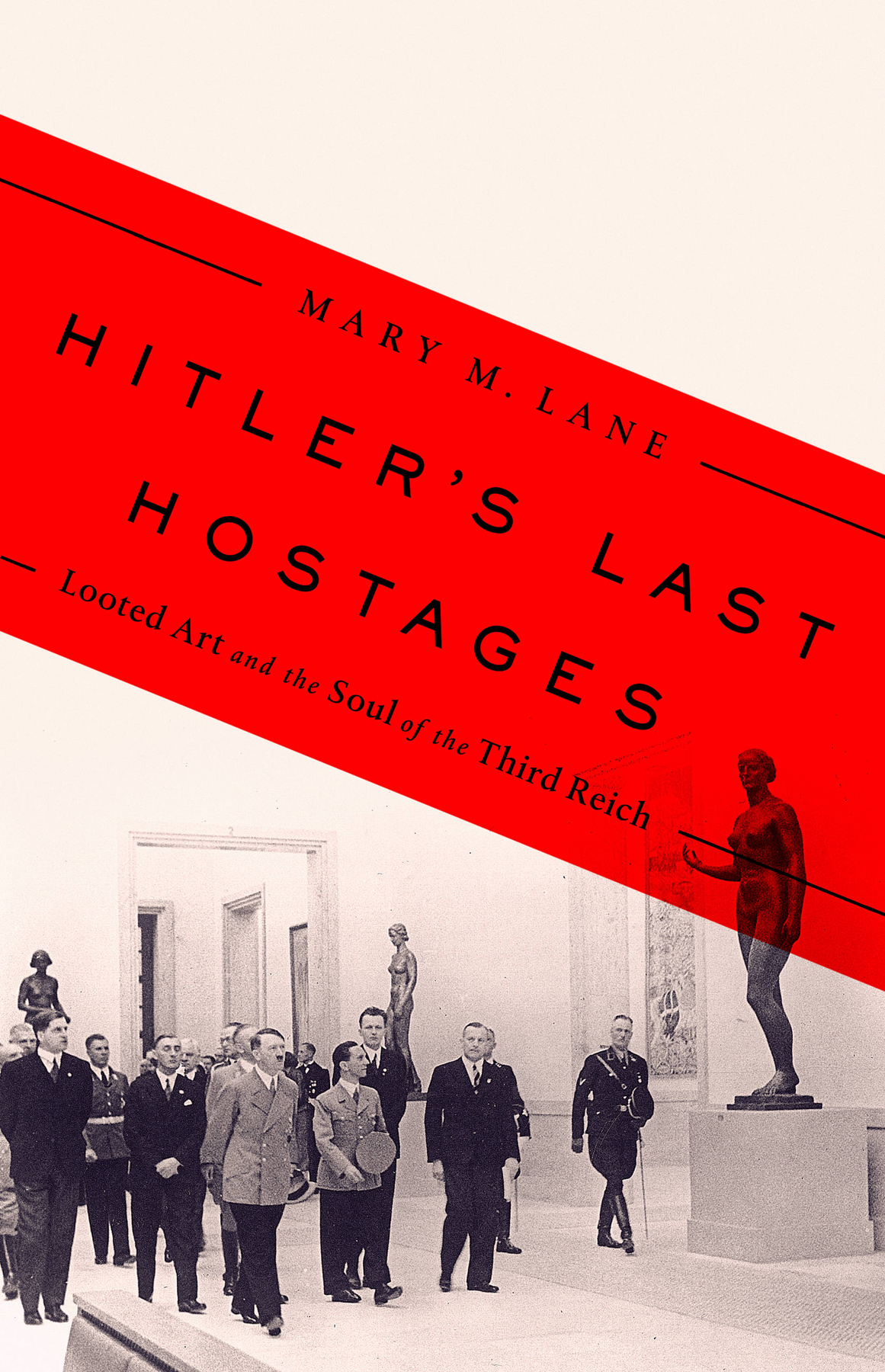

Copyright 2019 by Mary MacPherson Lane

Cover design by Pete Garceau

Cover image copyright Keystone / Getty Images

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: September 2019

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The PublicAffairs name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lane, Mary M., author.

Title: Hitlers last hostages : looted art and the soul of the Third Reich / Mary M. Lane.

Description: First edition. | New York : PublicAffairs, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019003411| ISBN 9781610397360 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781610397377 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Art theftsGermanyHistory20th century. | Art treasures in warGermanyHistory20th century. | Gurlitt, HildebrandArt collections. | Hitler, Adolf, 18891945Political and social views. | World War, 19391945Destruction and pillageGermany. | ArtMutilation, defacement, etc.GermanyHistory20th century. | GermanyCultural policy. | GermanyHistory19331945.

Classification: LCC N8795.3.G3 L36 2019 | DDC 364.16/2870943dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019003411

ISBNs: 978-1-61039-736-0 (hardcover), 978-1-61039-737-7 (ebook)

E3-20190810-JV-NF-ORI

F OR THE P ACK

S TELLA, B LAKE, J EX, AND, OF COURSE, D AVID

I N MANY A STRIFE, WEVE FOUGHT FOR LIFE

Art will always remain

the expression and the reflection

of the longings and the realities of an era.

Adolf Hitler

This Nazi shit will consume your life for the foreseeable future. Get used to it.

Senior Editor for the Wall Street Journal to the author, November 2013

A T AROUND 4 A.M. ON Wednesday, 6 November 2013, I was sleeping in a Manhattan hotel when I was awakened by one of my phones for the Wall Street Journal. The night before, I had been covering the annual Impressionist and Modern Art Auction at Christiesa night during which dealers, speculators, and private collectors had bought just shy of $144.3 million worth of art in roughly the amount of time it takes to watch a feature film. The auction had included works by artists whose careers I had grown accustomed to analyzing for both their artistic merit and their market valuea cold but critical balance in covering the worlds largest legal but unregulated industry. That night, Christies had sold a Vincent van Gogh work on paper for $5.49 million, a Claude Monet for $8.12 million andits top lota portrait by Pablo Picasso of one of his mistresses for $12.2 million.

On the phone, a Europe-based editor told me to return to Berlin immediately. This, he said, was bigger than New Yorks November Auction Week, the most lucrative time annually for the global art market.

What exactly was this, I asked groggily. Though I was the chief European art reporter, editors had told me to concentrate on New Yorks relationship with Europe that week rather than events in Europe itself. My editor told me that Focus magazine, a German cross between Americas Newsweek and People, had just revealed that an octogenarian recluse named Cornelius Gurlitt had been hiding approximately 1,200 works of art in his small Munich apartmentworks by the same artists I had just covered at Christies.

Focus said that Cornelius had inherited them from his father, Hildebrand Gurlitt, who had been one of the main art dealers for the Fhrermuseum, the museum Adolf Hitler planned to build to house Nazi-approved masterpieces, many looted from the Fhrers victims and from European museums. German government officials had confiscated the trove in early 2012 as part of a never-ending tax investigation. Yet they had concealed the troves existence for almost two years.

If the works were real, the collection was clearly worth tens of millions of dollars. There were pieces by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Pablo Picasso, Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse, Max Liebermann, and dozens of other artists whose names the German government refused to release. Germanys hiding of this find represented an egregious violation of the Washington Principles, a set of international regulations agreed to by Germany in 1998 intended to facilitate the return of Nazi-looted property to Hitlers victims.

The Journal asked me to investigate the case and write a Page One article on the lives of Hildebrand and Cornelius Gurlitt within seventy-two hours, ten of which would be consumed by travel. On the airplane, I contemplated the implications this story would have for Germany, the art world, and my career. I dozed in my cramped coach seat, preparing for several nights slumber under my desk in the Journals bureau, located across from the German parliament. I had recently turned twenty-six years old. Little did I know that I was embarking on a five-year project that would confirm that the wounds of World War II were hardly healed and clearly demonstrate that the German government was ill prepared to deal with this problem of international proportions.

On 9 November 2013, I published my first Page One article on the Gurlitt family for the Wall Street Journal, focusing on Hildebrand Gurlitt, the man who had been part of the elite group rounding up art across Europe in the 1940s. What I uncovered for that article and over the next several months was so bizarre, so cinematic, that even hardened Manhattan editors expressed astonishment at the Gurlitt familys historyand consternation at the German governments blas response.

In February 2012, Hildebrands son, Cornelius Gurlitt, an elderly, reclusive bachelor, had been resting in his apartment in Munich when he heard a sharp rap on the door. Within minutes, German tax investigators raided his house. Cornelius had caught their attention months before while transporting 9,000 in crisp 500 bank notes on a high-speed train from Switzerland. Because this amount was under 10,000, he was not required to declare it, but Corneliuss use of 500 notes, commonly used for money laundering in Europe, had aroused suspicion.

Raiding Corneliuss apartment, authorities were astonished to find roughly 1,200 artworks piled up like old newspapers in every nook and cranny. Cornelius had taken one Matisse painting, Woman with a Fan, a portrait of a pale-skinned brunette, and shoved it into a crate of tomatoes. On his living room wall hung Liebermanns