OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES 126

ACES OF THE REPUBLIC OF CHINA AIR FORCE

SERIES EDITOR: TONY HOLMES

OSPREY AIRCRAFT OF THE ACES 126

ACES OF THE REPUBLIC OF CHINA AIR FORCE

Raymond Cheung

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

R elatively little has been published in English on the Republic of China Air Force (ROCAF) and its fighter aces. What is available often does not do the subject justice for the simple reason of poor access to source data. Apart from the language barrier, there was the political turmoil in the region following the retreat of the Nationalist Chinese government to Taiwan in 1949. This volume, which takes advantage of better access to Chinese and Japanese records in recent years, will try to fill this gap.

In the bitter air fighting during the protracted eight-year war against Japan and the subsequent civil war against the Chinese Communists, the ROCAF produced 17 aces. These men came from a variety of backgrounds and scored their victories while flying a wide range of aircraft from biplanes to jets. Two received training from the Luftwaffe and one, quite incredibly, trained at the Japanese Army Air Forces Akeno Academy. The reason for this was, up until the eve of the Sino-Japanese War in 1937, China was a badly divided country. Military governors of the provinces fought against the Central Government and each other for dominance. The larger provinces even had their own air forces. Remarkably, it was only when faced with an invasion by Japan that all the factions came together and put up fierce resistance.

The Chinese Air Force (CAF) faced terrible odds. Japan had well-trained and well-equipped Army and Naval Air Forces backed up by a modern aviation industry. The Chinese, by contrast, were still in the process of building their air force when war broke out in 1937. With no aviation industry of its own, the Chinese relied on imported foreign combat aircraft. The Japanese mounted a highly effective naval blockade that hindered the delivery of these machines. Nevertheless, the Chinese gave a good account of themselves in the early stages of the war, producing 12 aces.

In 1940-41, the CAF was effectively knocked out of the war by the emergence of the vastly superior A6M Zero-sen fighter. It was only after the United States had entered the war and provided China with substantial amounts of military aid that the CAF was once again able to rejoin the fight. During this period five Chinese pilots became aces, including three who fought alongside USAAF pilots in the Chinese-American Combined Wing (CACW).

Please note that transliterations of names in Chinese are given in the form used during the war, rather than the modern Hanyu Pinyin.

Many friends and colleagues provided help and encouragement during this project, for which the author is most grateful. Special thanks go to the ROCAF; the Chinese Aviation Historical Society; Dr Wen, Liang-yan; Dr Yasuho Izawa; Gary Lai; Clarence Fu; Fu, Jing-hui; John Gong; David Chiao; Dong, X Y; Kamada, Minoru; Wu, Y D and Yeh, Daming.

CREATION OF THE REPUBLIC

T he Republic of China came into being in 1911 with the overthrow of the Imperial Manchu Dynasty. This followed a long period of weak and ineffective rule, with the loss of territory and rights through the Unequal Treaties forced upon China by encroaching foreign powers. The leader of the revolution, Dr Sun, Yat-sen, called for the establishment of a constitutional democracy modeled on the United States. However, like many other revolutions that were to follow, these idealistic principles were quickly subverted.

A military strongman, Gen Yuan, Shi-Kai, got himself elected president. He then dissolved parliament, purged followers of Suns Nationalist Party and forced Sun into exile. Yuan appointed military governors to each of the provinces, and they had control over local taxes and could raise their own military forces. Yuan declared himself emperor in 1915 and was, in turn, deposed. With troops, and the means to finance them, the military governors of the provinces found themselves with great power and influence. They became known as warlords as they fought each other for dominance in government, and years of chaos and civil wars duly followed.

There is one interesting side note from the Warlord Period. Chekiang Province had a small air force that lasted about seven months in 1924 before it was absorbed by another warlord following the Jiangsu-Chekiang Conflict. A small air arm of a minor warlord would have been of little historical interest but for the fact that its commander was Etienne Tsu (  , Tsu Bin-hou). Tsu was originally from Shanghai and he went to college in France. Fascinated with aviation, Tsu obtained his pilots licence in 1914. Upon the outbreak of World War 1, Tsu volunteered to fight for France. He was assigned to Escadrille N37 of the French Aronautique Militaire and saw action in 1916-17, scoring three confirmed aerial victories two German aircraft and one observation balloon. He was also credited with two enemy aircraft forced to land, which, according to some aviation historians, makes Tsu an ace.

, Tsu Bin-hou). Tsu was originally from Shanghai and he went to college in France. Fascinated with aviation, Tsu obtained his pilots licence in 1914. Upon the outbreak of World War 1, Tsu volunteered to fight for France. He was assigned to Escadrille N37 of the French Aronautique Militaire and saw action in 1916-17, scoring three confirmed aerial victories two German aircraft and one observation balloon. He was also credited with two enemy aircraft forced to land, which, according to some aviation historians, makes Tsu an ace.

During the Chinese civil wars of the 1920s, two of Chinas closest neighbours and regional rivals, the Soviet Union and Japan, supported rival factions. As a result of its victory in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05, Japan had assumed control of the Kwantung Leased Territories from Russia. The governor of the territories, called Kanto-cho in Japanese, had a large, modern Kwantung Army at his disposal. The Kanto-cho governor supported the government in Peking, which was also backed by warlords of the Northern Faction.

One of the most powerful warlords in the Northern Faction was Marshal Chang, Tsuo-lin, the military governor of the three resource-rich eastern provinces known to the West as Manchuria. Chang, nicknamed the Old Marshal, had the largest army, and he also started building an air arm (the Manchurian Air Force) as early as 1920. It duly played an important role in the fighting against rival warlords in 1922 and 1924. By the late 1920s, the Manchurian Air Force was the largest in China.

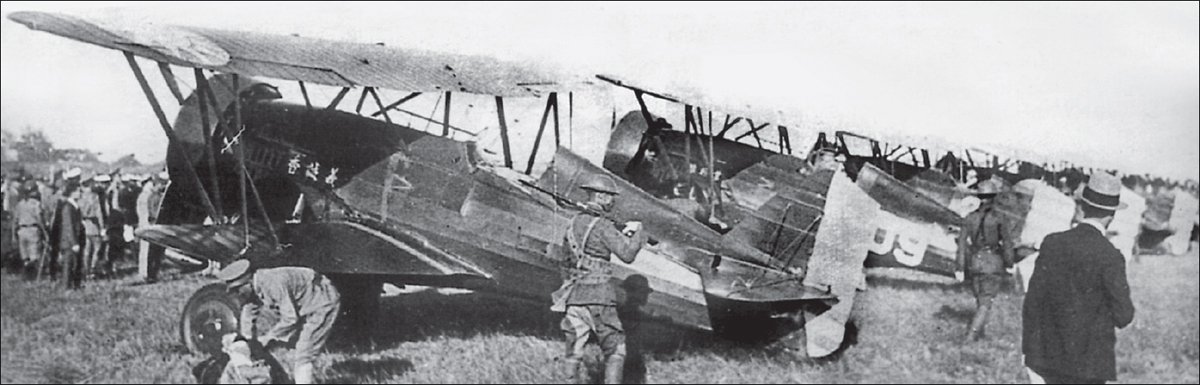

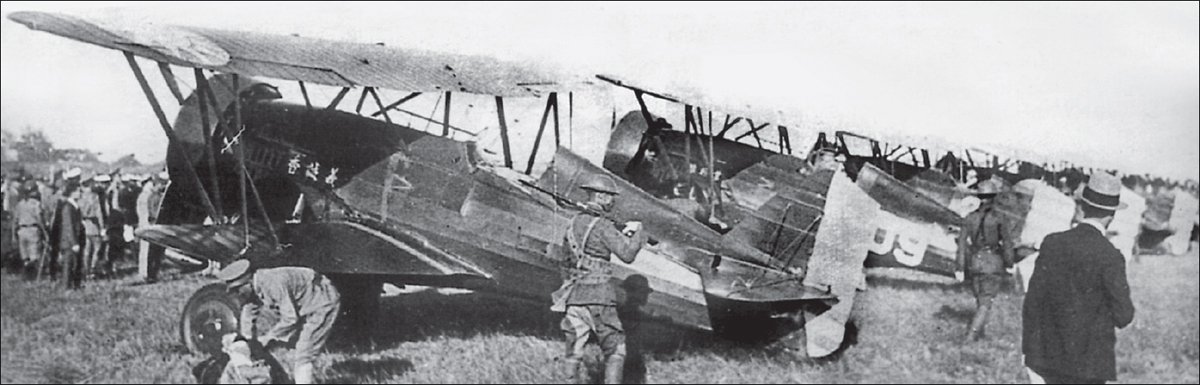

Newly delivered Hawk IIIs with Chinese inscription on their noses. The closest aeroplane honours the businessYi Cheng Hsiang(  ), an inn or hotel in the city of Paoting that donated money to finance its purchase. Unlike the remaining Hawk IIIs in this photograph, the aircraft has yet to have its large fuselage side number applied. This shot was probably taken during a public display held before the Sino-Japanese War erupted. It is believed that many CAF aircraft featured inscriptions prior to the conflict. Unfortunately, few photographs were taken at the time, and even fewer have survived into the 21st century. This, coupled with the loss of CAF records, means that it is impossible to match inscriptions to aircraft numbers (All photographs courtesy of the Aviation Historical Society of the Republic of China [AHSROC] unless otherwise specified)

), an inn or hotel in the city of Paoting that donated money to finance its purchase. Unlike the remaining Hawk IIIs in this photograph, the aircraft has yet to have its large fuselage side number applied. This shot was probably taken during a public display held before the Sino-Japanese War erupted. It is believed that many CAF aircraft featured inscriptions prior to the conflict. Unfortunately, few photographs were taken at the time, and even fewer have survived into the 21st century. This, coupled with the loss of CAF records, means that it is impossible to match inscriptions to aircraft numbers (All photographs courtesy of the Aviation Historical Society of the Republic of China [AHSROC] unless otherwise specified)

The Soviet Union, wary of the Japanese presence in China, supported a small but growing Chinese Communist Party. Stalin also realised that he needed a more powerful ally to counter the Japanese influence. He supported Sun, Yat-sens Nationalists, which had retreated to Suns southern province of Kwangtung (known to the West as Canton). The Nationalists began building an army for a Northern Expedition to wrest control of China from the warlords and unify the country under one central government. The Soviet Union provided arms and advisors to support this effort, including aircraft and pilot training.

Next page

, Tsu Bin-hou). Tsu was originally from Shanghai and he went to college in France. Fascinated with aviation, Tsu obtained his pilots licence in 1914. Upon the outbreak of World War 1, Tsu volunteered to fight for France. He was assigned to Escadrille N37 of the French Aronautique Militaire and saw action in 1916-17, scoring three confirmed aerial victories two German aircraft and one observation balloon. He was also credited with two enemy aircraft forced to land, which, according to some aviation historians, makes Tsu an ace.

, Tsu Bin-hou). Tsu was originally from Shanghai and he went to college in France. Fascinated with aviation, Tsu obtained his pilots licence in 1914. Upon the outbreak of World War 1, Tsu volunteered to fight for France. He was assigned to Escadrille N37 of the French Aronautique Militaire and saw action in 1916-17, scoring three confirmed aerial victories two German aircraft and one observation balloon. He was also credited with two enemy aircraft forced to land, which, according to some aviation historians, makes Tsu an ace.

), an inn or hotel in the city of Paoting that donated money to finance its purchase. Unlike the remaining Hawk IIIs in this photograph, the aircraft has yet to have its large fuselage side number applied. This shot was probably taken during a public display held before the Sino-Japanese War erupted. It is believed that many CAF aircraft featured inscriptions prior to the conflict. Unfortunately, few photographs were taken at the time, and even fewer have survived into the 21st century. This, coupled with the loss of CAF records, means that it is impossible to match inscriptions to aircraft numbers (All photographs courtesy of the Aviation Historical Society of the Republic of China [AHSROC] unless otherwise specified)

), an inn or hotel in the city of Paoting that donated money to finance its purchase. Unlike the remaining Hawk IIIs in this photograph, the aircraft has yet to have its large fuselage side number applied. This shot was probably taken during a public display held before the Sino-Japanese War erupted. It is believed that many CAF aircraft featured inscriptions prior to the conflict. Unfortunately, few photographs were taken at the time, and even fewer have survived into the 21st century. This, coupled with the loss of CAF records, means that it is impossible to match inscriptions to aircraft numbers (All photographs courtesy of the Aviation Historical Society of the Republic of China [AHSROC] unless otherwise specified)