Also by Nol Riley Fitch

Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation:

A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties

Walks in Hemingways Paris

Literary Cafs of Paris

Anas: The Erotic Life of Anas Nin

The Grand Literary Cafs of Europe

Paris Caf: The Select Crowd

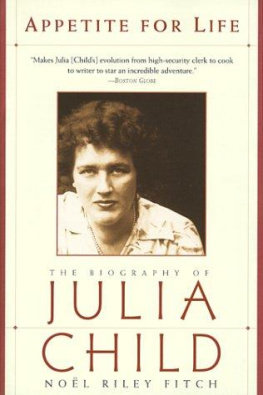

I NTRODUCTION TO THE 2012 EDITION OF

A PPETITE FOR L IFE

H OW WONDERFUL a friendship that can survive a biography, Julia Child wrote me after the 1997 publication of my Appetite for Life, the only biography she authorized.

It was more than seven years earlier that the Julia seed had been planted in my minda reluctant germination that had occurred in Paris, at the suggestion of two culinary historian friends, with the smell of roasting lamb and a large zucchini tart wafting in from their kitchen. To be perfectly honest, my first unexpressed thought was Do you mean that funny old lady on television? My face must have revealed this emotion, for my friend launched into a firm argument and lengthy analysis of Julia Childs great contribution to the way Americans thought, cooked, and ate. All your books are about the Franco-American literary connection, Nol, my friends pointed out. Why not do the significant culinary connection between the two countries? You are a voracious consumer of all food French. My hosts folded their argument nicely into the flavors of each course during the coming hours. By the time I smelled the rich aroma of roasting coffee beans for the espresso, I was giving their suggestion serious attention.

After some contemplation, I decided to approach the reigning American culinary queen herself. By then I had learned much about her childhood (her deep family roots in New England and the Midwest; her idyllic childhood in California; her studies at Smith, her wartime action for the [pre-CIA] Organization of Strategic Services in India and China). I knew also that she had a love affair with Paris and the lost generation. Mrs. Childshe hated the appellation Ms.was neither thrilled nor dismayed when I told her that I was thinking about writing her biography. Oh, I am much too busy, dear, she said with finality. The thought of lengthy interviews appalled her. She had rejected the idea of a biography or an autobiography on a number of occasions. I assured her that I was accustomed to working on biographies of subjects who were no longer living, so I knew how to do my researchand that meant I would stay out of her way. What seemed to please her most is that I wanted to write a book like my first book, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the Twenties and Thirties. I would tell her story in the larger context of the French-American culinary connection. She seemed relieved that I was still busy writing another book, a biography of diarist Anas Nin. She admired my work, she said, and if I decided to write her story after Anas, she would help and not hinder. Thus, we could spend the months ahead (she probably hoped years, to put off the book itself) thinking about her biography and getting acquainted.

Early in our correspondence, Julia wrote that we must come visit her at La Pitchoune (the little one), her country home in Provence. That summer, 1992, would be her final sojourn there. Then she wrote what was for me the most encouraging news: I have no objections to a biography of me as long as I dont have to do anything about it. I am neither for or against it, actually . I would of course give you access to any papers you wish to have, either here or at the Schlesinger Library, and am flattered that you are thinking of doing anything!

My husband and I visited Julia in June 1992 at La Pitchoune. There I met some of her sister Dorothys family, including her tall young niece, Phila. They were packing Julias worldly goods to vacate the home that she and Paul had built on the property of her writing partner, Simone (Simca) Beck. With Paul Child in a nursing home and Simca now dead, Julia had little reason to return to their beloved French home and so, as agreed upon long ago, the home and land would revert back to Simcas family. The abiding image I took from that loving family farewell to Provence was the photograph of Julia above her fireplace mantel, a large photo taken by Paul of Julia in blue jeans and a plaid shirt, lying amid tall grass, her hands under her head, with a long piece of grass in her teeth. Peace and serenity on her face. The essence of her joie de vivre. Her appetite for lifeI had my inspiration for the title.

Before leaving France that summer, my decision to write Julias biography became irrevocable when a package of letters arrived. This is to let you know that I have given permission to Nol Riley Fitch to be my official biographer read my copy of Julias letter to Barbara Haber at the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe, where the Child papers were housed. To me Julia added: Yes, I would be happy to give you exclusive rights as a biographer . In other words, anything you need is available to youthere are no secrets. Your having access to things would not bother me, as long as I dont have to do anything, since I am absorbed in my workas you are too.

In early December of 1992, I made my first foray into the inner vault of Julias life to read her personal papers, as well as the in-progress professional papers that she had not yet given to the Schlesinger Library. I stayed with a writer friend (and during later visits, in a hotel) to preserve my biographers distance. The supreme and unenviable tightrope a biographer walks is the tension between empathy and objectivity. Biographers can fall onto one side or the other, into hagiography (easy with a much-beloved subject) or harsh analytical characterization, even character assassination. The tightrope is far more perilous if the biographer has a living subject, with whom she is acquainted. Familiarity can be both a blessing and a curse. In Cambridge, as in Plascassier, though guest beds were available and offered at both of Julias homes, I stayed nearby.

The Childs large white clapboard house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, almost backed onto Harvards property, but it was separated by a street occupied by such luminaries as Kenneth Galbraith, Arthur Schlesinger, and later Henry Louis Gates, Jr. The Childs street had housed at various times Henry James, Gertrude Stein, and Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. When I first arrived at her side door, she had deliberately chosen a week during most of which she would be making appearances elsewhere. Opening the door, she welcomed me with I have nothing to hide, Nol. I later learned that she and Paul enjoyed reading biography, so she had an understanding of my work and that it indeed was to be my book. Her office staff was to show me every filing cabinet, cupboard, and drawer. I must look at everything, she insisted.

I had already interviewed the first of dozens of her friends and family, but had not yet reached that necessary place when I could say, I got her! I know her! Julia showed me every detail of her kitchen, from the peg-board built by Paul for her pots and pans to the Paris mortar and pestle. She would cook for me, as she did later that week (tuna fish sandwiches, by the way), and we would eventually dine together in restaurants on two continents. But I kept the biographers distance evenor especiallywhen asking an intimate question.