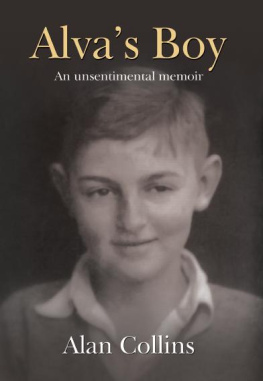

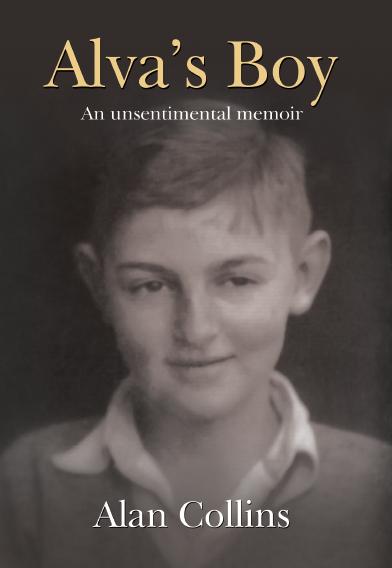

ALVA'S BOY

An unsentimental memoir

ALAN ALVA COLLINS was born in 1928 in Sydney. His mother died in childbirth, leaving him in the care of his father and a number of charitable children's homes. At fifteen he became an apprentice printer, and subsequently a reporter for a Sydney newspaper. By 1949 he was editor of the Sydney Jewish News. He moved to Melbourne in 1953 and worked in advertising, opening his own agency in 1972. He had married Rosaline Fox in London in 1957 and brought her to Melbourne, where they raised their family in Box Hill. But Alan had always been drawn strongly to the sea, and in 1987 they moved to beachside Elwood, where he spent the last two decades of his life, writing fulltime. Alan Collins is the author of the trilogy A Promised Land? (2001), comprising The Boys from Bondi, Going Home and Joshua. He also published Troubles (1983), a collection of short stories. Alva's Boy was completed not long before his death in 2008.

ALSO BY ALAN COLLINS

BOOKS

Troubles: 21 short stories (1983)

The Boys from Bondi (1987) *

Going Home (1993)

Joshua (1995)

A Promised Land? (2001)

* Published in the US as Jacob's Ladder (1989)

AUDIO

The Boys from Bondi, Going Home and Joshua

were also recorded by Louis Braille Books

PLAY

Shabbatai!

Published by Hybrid Publishers

Melbourne Victoria Australia

2008

This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the publisher. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction should be addressed to Hybrid Publishers,

PO Box 52, Ormond 3204.

First published 2008

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Author: Collins, Alan, 1928-2008

Title: Alva's Boy

ISBN: 9781876462666 (pbk.)

Subjects: Collins, Alan - Childhood and youth

Jewish children - New South Wales - Sydney - Biography

Dewey Number: 920.71

Digital editions published by:

Port Campbell Press

Epub ISBN: 9781877006043

www.portcampbellpress.com.au

Cover photographs of young Alan Collins and of

Alva Davis courtesy of the author

Cover design: Dynamic Creations

For Rosaline

and the family

I never thought

I would have.

Foreword

Truth is only believed when someone has invented it well.

George Santayana

This book is a work of non-fiction based on the life experiences and recollections of a Jewish childhood over a time-span from 1928 to the early 1940s. In some of the telling, names of people, places and dates have been changed. Mercifully, those named who are or were of a repellent nature have long since 'gone to God'.

The stories present incidents from the life of one person, the first-person narrator. The memoir is purposely unsentimental. The writer has worked hard to circumvent cheap emotion. Some readers might find it confronting. The linked stories encompass a child's unsparingly honest observations as he is buffeted by events which range from indifference and naked cruelty to sparkling life-affirming exuberance.

The publishers are not expected to warrant the veracity of what the author has provided.

A.C.

...1...

I was born in late September 1928, a particularly busy time in the Jewish calendar, encompassing the New Year and the Day of Atonement as well as the Feast of Tabernacles and the Festival of Rejoicing in the Law. This last marks the end of one reading of the scrolls containing the Five Books of Moses and the beginning of the new cycle. It is one of the few occasions when Jews, lay and clergy, can get joyously drunk without admonition. It was bad luck for me; I was comforted by those in the know and told that to be born on Yom Kippur was a blessing, a happy event.

As it happened, no glasses were raised in l'chaim; I was unceremoniously put to one side while my mother, the poor doomed Alva Phoebe Collins nee Davis, fought for her life, haemorrhaging critically while the only professional help at hand was a midwife. She employed her limited skills in an attempt to save my mother, at the same time casting around for the doctor who at that moment was mortifying himself with prayer and fasting in a synagogue a mile or so away. My father, enjoying an all too brief period of prosperity, had insisted that the accouchement be in the bedroom of his recently acquired Bellevue Hill mansion, a sandstone and brick 'gentleman's residence' clinging to the steep, grassy hillside. The furnishings had come from Bebarfalds store in George Street, Sydney, chosen by my father with a sweep of his arm around the various departments. My mother's input did not extend beyond flattening her swollen body against the walls as the gang of burly furniture men reassembled the store's showrooms in her new home.

And now she lay dead in a pool of blood and placenta, her olive skin blanched and with beads of sweat that would all too soon turn to icy pinpoints. My father, Sampson Collins, abused the newly installed wall-mounted telephone for its inability to connect him with his doctor - any doctor - who might re store life to his 27-year-old wife of little more than a year. He rounded on the midwife with an illjudged mixture of abuse and supplication until the woman raised her arm to strike him, paused in mid-sweep and then let her arm fall in a defeated, dejected gesture that ended in her tenderly pulling a covering over the body. Sampson Collins let the receiver dangle, sat on a carved Chinese chest at the foot of the bed and stared hard at the outline of my mother's body. Around his feet, a squat oriental satyr drank tea and gloated over pubescent girls. The midwife lifted me from the cradle (Bebarfalds: anybody for the fourth floor? - all nursery requirements) and carried me to the bathroom where she unwrapped me and washed me, then drew her dress aside and guided me onto her breast.

My mother was one of three sisters all of whom had the honeyed skin and warm dark eyes of the Sephardic Jew. Together with their mother, widowed before she was 40, they lived in a spacious ground-floor flat in what were then the sandhills of Rose Bay and contiguous with Bondi. The district was an enclave of Jews, most of whom would soon feel the 1930s Depression deeply, especially the men with no skills who could not handle a saw or dig a hole. Most of them had already lost the portable skills of the tailor or watchmaker that had at least provided their parents with bread. Those same parents who could ward off starvation and the pogroms of Eastern Europe had not passed on their survival skills to the next generation living in Bondi. It soon became clear that the relief work handed out by a government held in thrall to the Bank of England was the right of the goyim, nonJewish worktoughened men with wiry wives and kids able to subsist on the proverbial smell of an oily rag.

If I do not dwell too kindly on my father, it is because I invest in him my entire stock of misery. From photographs, he appears to have been a man of rakish elegance. The 'mashers' of their day were men who, regardless of the amount of cash they could jingle in their pockets, considered themselves irresistible to women. They wore tight suits, twotoned shoes with spats and managed to refresh their frayed cuffs with Harper's Silver Star starch. My father was mostly in work. He was a commercial traveller selling men's costume jewellery - the studs, cravat pins and cufflinks that the nobs needed to set off their 'soup 'n' fish' - dinner suits. Later, as the Depression bit deep, he went door-to-door buying scrap gold. But in this earlier, present occupation he was at one with the commercial travelling fraternity, the selfstyled knights of the road who met in the bar of the Commercial Travellers' Club to swap stories about the sales-ladies in the shops they called on.

Next page