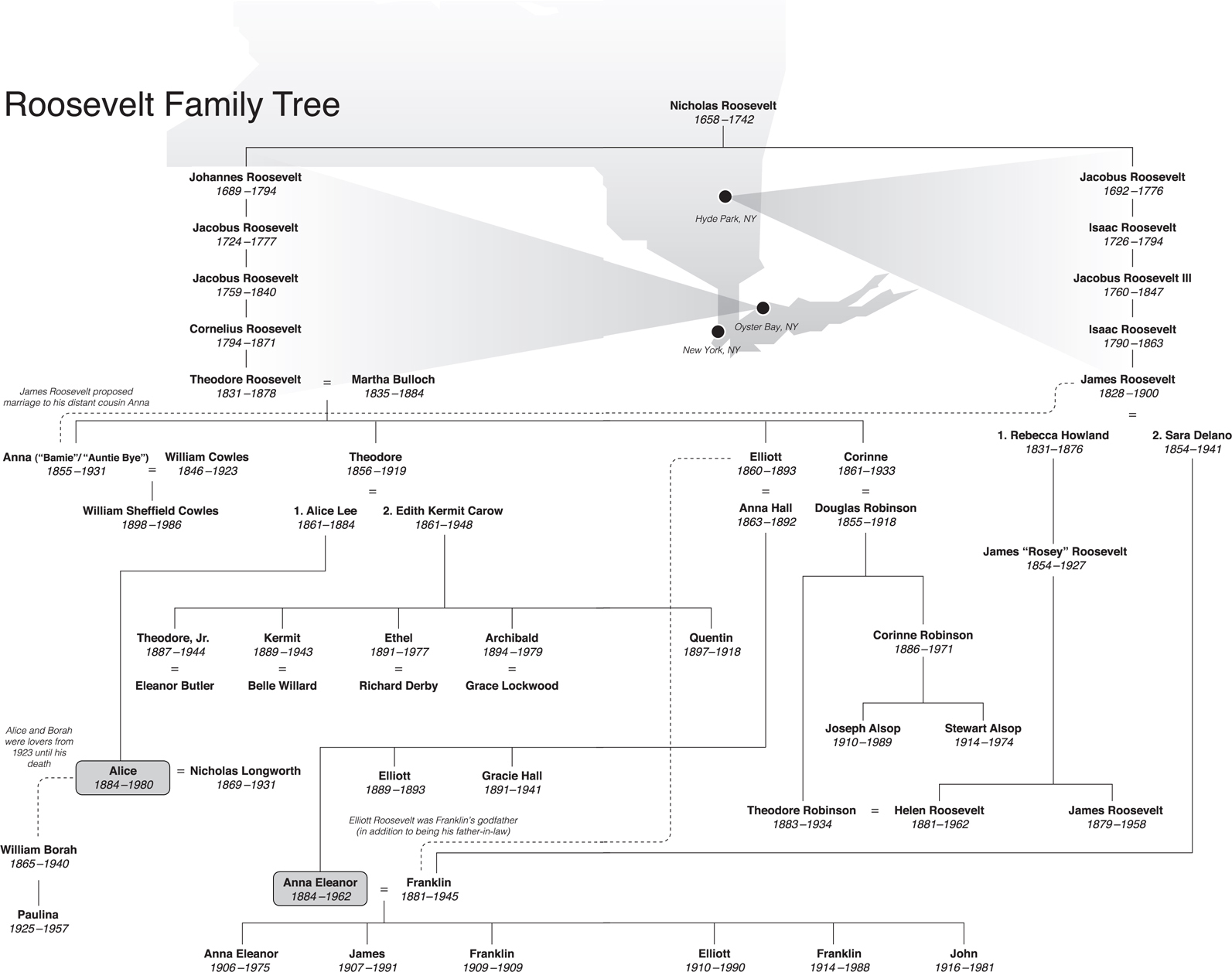

To view a full-size version of this image, click HERE.

Chapter 1

ORPHANS

E leanor Roosevelt hoped no one would come to her funeral. What she really wanted was to scotch the whole affair and just have someone announce her death after shed already been buried. Id like to be remembered happily if that is possible, she said. If that cant be Id rather be forgotten. Forgotten? I had to tell her, said her friend William Turner Levy, that she was being unrealistic.

Unrealistic, but not surprising. After all, this was the famously unfussy First Lady who served hot dogs to the king and queen of England during their 1939 state visit, who dragged her own suitcase around the world on countless humanitarian missions, and who insisted, after her husband died, that shed never do anything newsworthy again. Naturally, she wanted her afterlife to be just as unpretentious as what came before. Just a plain pine coffin covered with pine boughs. Inside the coffin are to be plain pillows and sheet with cloth, shed written in a letter to her doctor years earlier.

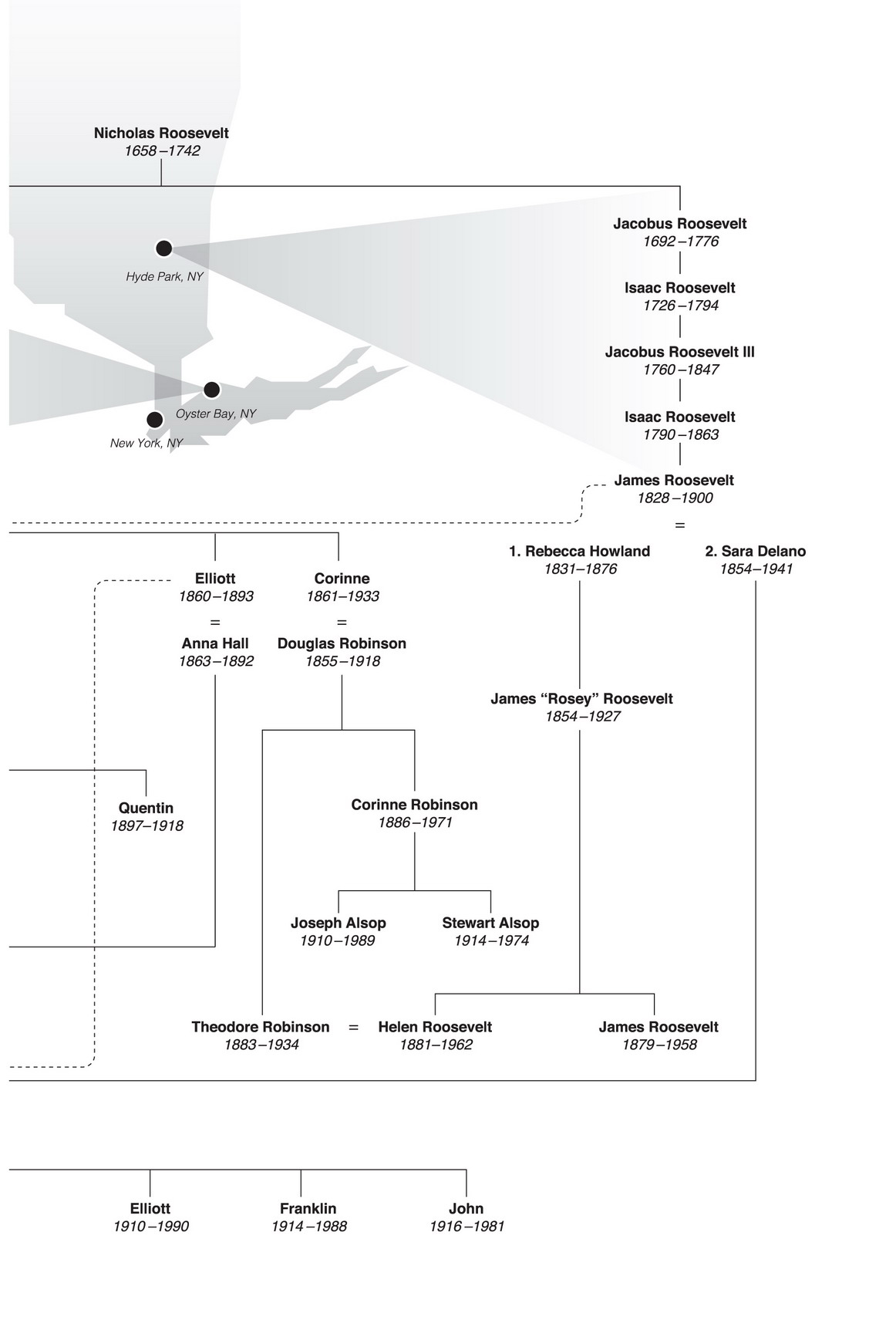

The service was held in Hyde Parks St. James Church, which seated just 250 people. Among those who didnt make the guest list: Horace W. B. Donegan, the grandstanding Episcopal bishop of New York. The five Roosevelt children refused to invite him, dreading he would eulogize their mother at length. (He showed up anyway but otherwise kept quiet.) Even the weather seemed to cooperate with Eleanors wishes. November 10, 1962, was a cold, damp day with the wind blowing off the Hudson River and pushing the chill through the streets of the town.

Yet the mourners, like the good bishop, werent going to let a cold shoulder stop them from saying good-bye. Thousands lined the roads, some standing five-deep to watch the hearse carry Mrs. Roosevelt from St. James to the Roosevelt mansion, Springwood, two miles away. For generations, the Roosevelts of Hyde Park had been buried in the quiet graveyard behind the little church, but President Roosevelt had requested that he and Eleanor be laid to rest in the large rose garden just to the side of the family home. It was, in its way, the perfect spot. After all, Roosevelt in Dutch means field of roses. Perhaps just as important, FDRs overbearing mother, Sara, was tucked a safe distance away, resting in uncharacteristic silence back behind the church.

The presidents arrangement, however, helped produce exactly the kind of funeral Eleanor wanted to avoid. It was as if someone had picked up the entire Macys Thanksgiving Day Parade and dropped it into small-town America. The nightly news, including the BBC, delivered extensive coverage. Limousine-lock tied up the roads; amid all the excitement, two local keystone cops crashed their cruisers into each other right in front of the Hyde Park state police barracks. Most people were fans, but there were haters, too. One man standing along the funeral route waved a sign that read, Im glad youre dead, Eleanor.

The roster of invited guests might have been small, but it was A-plus-list. President and Mrs. Kennedy arrived on Air Force One (which was taking its maiden voyage and would be used, almost exactly one year later, to transport JFKs body back from Dallas). Vice President and Mrs. Johnson came, as did the former presidents Truman and Eisenhower, making this the first time that three presidents attended the funeral of a First Lady. Chief Justice Warren, Secretary of State Rusk, Secretary of Defense McNamara, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, Governor Rockefeller of New York, the United Nations ambassador Stevenson, and a sizable contingent of the Washington establishment were there. One well-aimed Soviet missile would have decimated the U.S. government.

That was no idle concern. Mrs. Roosevelts funeral came at the tail end of the Cuban missile crisis. Just days earlier, Nikita Khrushchev had agreed to dismantle the Soviet missiles hed lined up in Cuba like cigars ready to be lit, and Castro was still threatening to shoot down anything bigger than a kite that wandered into his airspace. The U.S. military was so concerned, the Pentagon wanted to install a kind of hotline in the pew at St. James where President Kennedy was to be seated. The Reverend Gordon Kidd said no. If he had to talk on the phone during the service it would be terribly frustrating and confusing, Kidd reasoned. When he popped in for a visit at her woodsy Val-Kill cottage two years later, Eleanor had only one real worry. She realized she had no vodkaeven though Khrushchev was coming at 7:00 a.m. (Her son John dutifully ran down a bottle.)