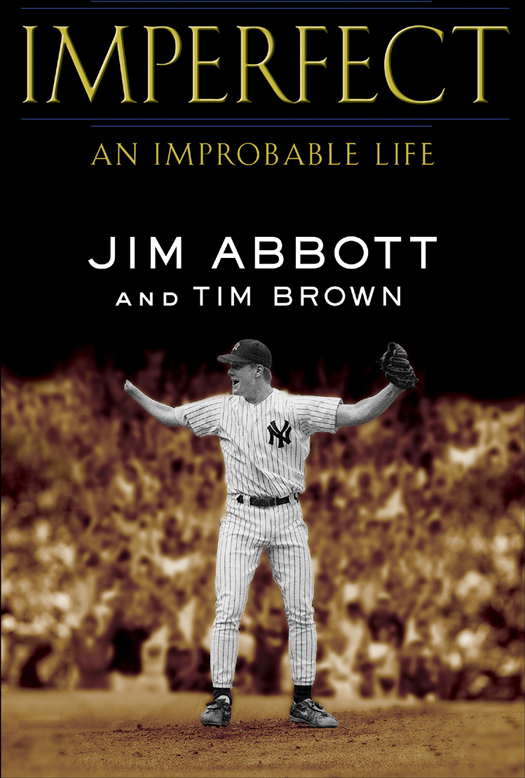

Copyright 2012 by Jim Abbott

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

B ALLANTINE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Abbott, Jim

Imperfect : an improbable life / Jim Abbott and Tim Brown.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-52327-3

1. Abbott, Jim. 2. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography.

3. Pitchers (Baseball)United StatesBiography. 4. Athletes with

DisabilitiesUnited StatesBiography. I. Brown, Tim. II. Title.

GV865.A26A3 2012

796.357092dc23 [B] 2012001917

www.ballantinebooks.com

Jacket design: David Stevenson

Jacket photograph: Richard Harbus, NY Daily News

v3.1

Contents

So, what are you going to do about it?

H ARVEY D ORFMAN

Introduction

E lla is my youngest.

She has my hair and eyes and her mothers smile. The timing is distinctly hers. She was five when she asked, quite publicly, Dad, do you like your little hand?

My what? Do I like it?

I had come to her preschools Career Day bearing baseball cards for her classmates. In the morning rush getting the girls through the front door and into the car, Id packed into a gym bag a couple familiar baseball caps, an Olympic gold medal, and a baseball glove.

I had come first as a dad, and then as a former baseball player. Id pitched for the local team, the California Angels, and for the team everybody had heard of, the New York Yankees. I had come because I wasnt pitching anymore, and because Ellas mother, my wife, Dana, wryly pointed out that preschool Career Day wasnt really for fathers who no longer had careers. The query, posted on the door of Ellas classroom weeks before, read: Do any of the dads have an interesting job they could come and speak to the children about? When I arrived one afternoon to collect Ella, the answer beside her name on the door, in Danas handwriting, read, No. Calling her on the playful taunt, Id scratched out No and written Yesbaseballpresumably precisely as she had intended.

Ella had been excited. The classroom had hummed, curiosity over the stranger in the room sparring with the early-morning Capn Crunch joggling.

Id seen hundreds of similarly occupied, similarly distracted schoolrooms, and every one of them put me back at my own tiny desk in my own childhood in Flint, Michigan.

At any age, I was the kid with the deformity. At Ellas age, I was the kid with the shiny and clunky metal hook where his right hand should have been.

Thirty-five years later, classrooms remained among the few places where I was conscious of my stunted right hand. I would enter and later find I had slipped it into my front pants pocket, tethered against unconscious gesturing, signaling to the room that the details of its story would come at my choosing, if at all.

In this particular room, its walls lined with finger-paint art and construction paper trimmed by tiny round-tipped scissors, I was introduced first as Ellas dad and second as a guy who once pitched in the major leagues. Every eye in the room went to the place where my hand should have been. They always did, no matter the demographic.

I started, slowly.

Who knows their Angels? The Yankees? Whos your favorite? Does anyone play baseball?

I was getting to the subject of my hand, building toward it, the courteously unasked question even among preschoolers. The baseball glove was on the desk before me, awaiting the demonstration, how I threw it, caught it, threw it again. I scanned the room for a kid who looked athletic enough for an easy game of catch, so that Career Day didnt end in a broken nose and Emergency Room Day.

A five-year-old hand went up. My brother plays baseball.

Another. Do you have a dog?

A third. Ellas.

Do I like it?

I had never thought of my birth defect in terms of liking it. Id disliked it some, found it a nuisance at times, hardly thought about it at others. I didnt remember it being called a little hand, and certainly not by Ella.

We never called it that at home. We never called it anything.

Mostly, my relationship with my hand and its various consequences was blurred, and often complicated. Its permanence bobbed in a current of all it might have taken from me and all that it offered. It carried me where it would, to frustration and reluctance, and to fear, but also to the resolve to thrash against its pull. From the moment I could understand Id been so cast, my parents had championed my opportunity to thrash. Special people, they said, endured against the disability, the child born imperfectly. As significant, special people endured against what the disability incessantly drew: the self-pity, the ignorance, the rationalizations of a life less fully spent. I didnt know about special, but I knew I wanted to endure, and I knew it pleased themand mewhen I did, when I was up to the fight.

Ive wondered from time to time if I was carrying it, or it me. Mostly, I think, I did the heavy lifting. My parentsKathy, my mother, returned to school and became an attorney when I was in my teens, and Mike, my father, was a sales manager for Anheuser-Buschgenerally declined to stand as shields. As far as I know, they werent at my schools asking for favors, or whispering to the youth-league baseball coach to keep me out of the infield, or standing in an upstairs bedroom window, making sure the kids in the yard played nice. I really sort of found my own way through.

Baseball helped. It leveled the playing field, then placed me above itten and a half inches above it, on the pitchers mound. The rest was about results, and not about who learned to tie his shoes first or who could button his shirt fastest or who looked like what. I remember once feeling dissatisfied with a professional career in which I lost more than I won, and that ended soonerand with far more heartachethan I hoped it would. My mother reminded me of the journey I had taken, how at every step I had longed for the next one, and only the next one. In the Flint youth leagues, I had simply wanted to be good enough to play with the next age group. Soon, I aspired to be good enough to pitch at the big public high school. Then in college, the Olympics, professional baseball, the big leagues. Every level, she said, was, in its moment, a gift, every experience grander and more rewarding than the last. There was no rehearsed progression. It just happened. I think thats the way my parents thought of it, too. And I liked it just fine.

Did I like this hand, though? Could it be as simple as a childs curiosity, all black and white and no gray? I wondered if that really was what she was asking.

Do I like what I have been? How I have been looked at? The battles I chose? The ones that chose me? Those I evaded? What I became?

Do I like who I am?

It was a lot to consider standing in front of a dozen five-year-olds, the morning frivolity undone by my desire to be truthful, and then to reexamine a life spent at the blunt end of inspection, followed inevitably by introspection. The teacher, Ms. Roberts, white-haired and not typically indulgent, held her gaze from the rear of the room. This, she could be reasonably sure, was going to be more interesting than last weeks stockbroker.