This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1986 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

CSI Report No. 11 Soviet Defensive Tactics at Kursk, July 1943

By

Colonel David M. Glantz

Director of Research Soviet Army Studies Office Combined Arms Center

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

Introduction

In his classic work, On War , Carl von Clausewitz wrote, As we shall show, defense is a stronger form of fighting than attack. A generation of nineteenth century officers, nurtured on the study of the experiences of Napoleon and conditioned by the wars of German unification, had little reason to accept that view. The offensive spirit swept through European armies and manifested itself in the regulations, plans, and mentality of those armies. It also blinded all but a few perceptive observers to the carnage of the American Civil War, the Boer War, and the Russo-Japanese War, all of which suggested that Clausewitz dictum was perhaps correct. The catastrophe of World War I vindicated Clausewitz and grotesquely mocked those who placed such high hopes in the utility of the offensive.

Post-World War I armies understood well the power of twentieth century technology when harnessed to serve the military. Post-war military views, in general, echoed national political aims. Those nations wedded to maintenance of the political status quo sought to draw upon technology to strengthen military defenses and to deter those who would alter the political condition by use of offensive military power. Conversely, those nations shackled by the political settlements of World War 1 or compelled by ideology to seek change, sought to exploit new technologies in order to restore the viability of the offensive to the modern battlefield. Thus the Germans worked surreptitiously on developing blitzkrieg concepts, and the Soviets fixed their attention on achieving deep battle ( glubokiy boy ).

The events of 1939, 1940, and 1941 in Poland, France, and Russia respectively again challenged Clausewitz claim of the superiority of the defense and prompted armies worldwide to frantically field large armored forces and develop doctrines for their use. While blitzkrieg concepts ruled supreme, it fell to that nation victimized most by those concepts to develop techniques to counter the German juggernaut. The Soviets had to temper a generation of offensive tradition in order to marshal forces and develop techniques to counter blitzkrieg. In essence, the Soviet struggle for survival against blitzkrieg proved also to be a partial test of Clausewitz dictum. In July 1943, after arduous months of developing defensive techniques, often at a high cost in terms of men and material, the Soviets met blitzkrieg head-on and proved that defense against it was feasible. The titanic, grinding Kursk operation validated, in part, Clausewitz views. But it also demonstrated that careful study of force organization and employment and application of the fruits of that study can produce either offensive or defensive victory. While on the surface the events of Kursk seemed to validate Clausewitz view, it is often forgotten that, at Kursk, the Soviets integrated the concept of counteroffensive into their grand defensive designs. Thus the defense itself was meaningless unless viewed against the backdrop of the renewed offensive efforts and vice versa. What Kursk did prove was that strategic, operational, and tactical defenses could counter blitzkrieg.

Soviet Tactical Defense Prior to Kursk

Soviet victory on the Eastern Front was a product first and foremost of the Soviet defensive effort. Only successful defense could pave the way for offensive victory. Moreover, the development of strategic and operational defenses depended directly on the Soviet ability to stop German offensive action at the tactical level. Soviet development of effective tactical defenses was a long and difficult process. It involved changing the offensive mind-set of Soviet officers. It also entailed the training of a generation of officers capable of ably controlling forces at the tactical level and the fielding of equipment of the type and in the numbers necessary to conduct successful combined arms defense. Development of tactical defense concepts involved a process of education that began in June 1941 and continued throughout the war. The fruits of that education were apparent at Kursk.

The Soviet fixation on offensive forces, concepts, and techniques in the late 1920s and 1930s eclipsed similar work on defense at the strategic, operational, and tactical level. Soviet brainpower and resources focused on the creation of shock armies, mechanized forces, and airborne forces; all those elements critical to achieving strategic offensive success through the conduct of deep operations and deep battle. By the Soviets own admission, this fixation on the offensive caused them to pay too little attention to strategic ( front ), operational (army), and tactical (corps and division) level defensive operations as a deficiency vividly evident in 1941.

The 1936 Field Regulation demonstrated the Red Armys attitude toward defense. The tendency to view the defense as a temporary (and unpleasant) phenomenon forestalled Soviet development of a broad defensive doctrine that addressed such essential questions as requisite strength and integration of numbers and types of weapons necessary to forestall or parry enemy offensive action. The general neglect of defensive training was exacerbated by the ill effects of the military purges on the level of competence within all levels of command.

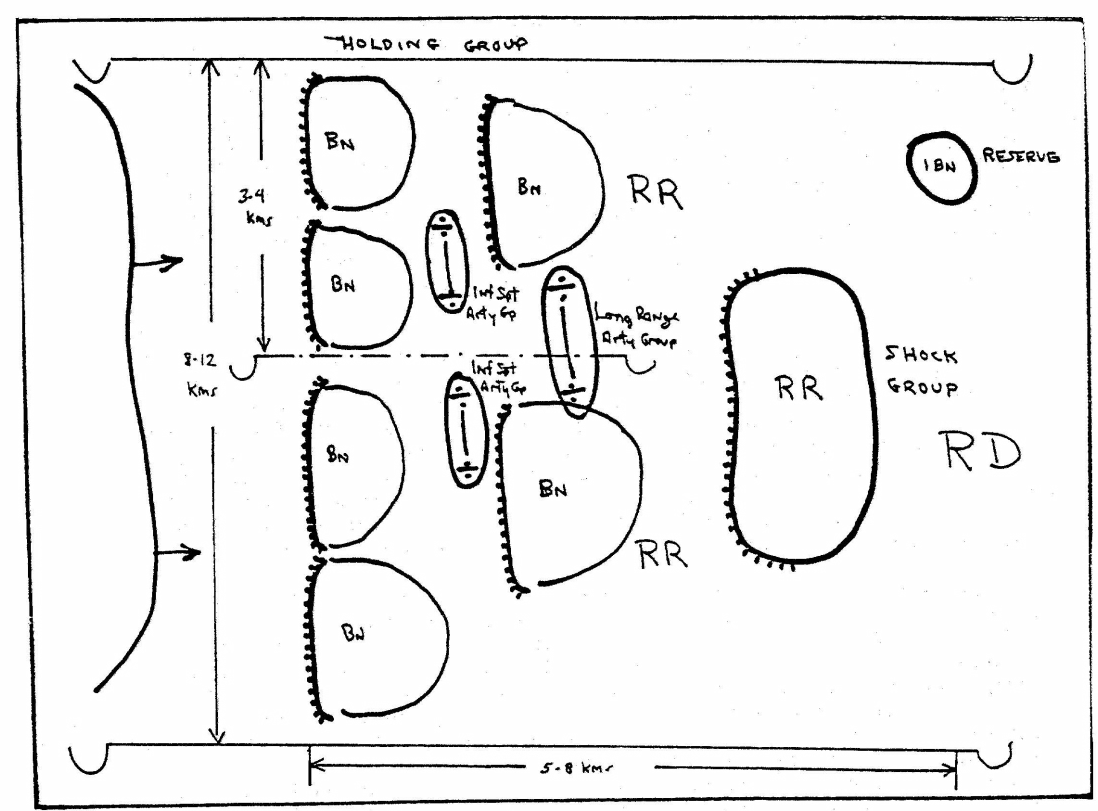

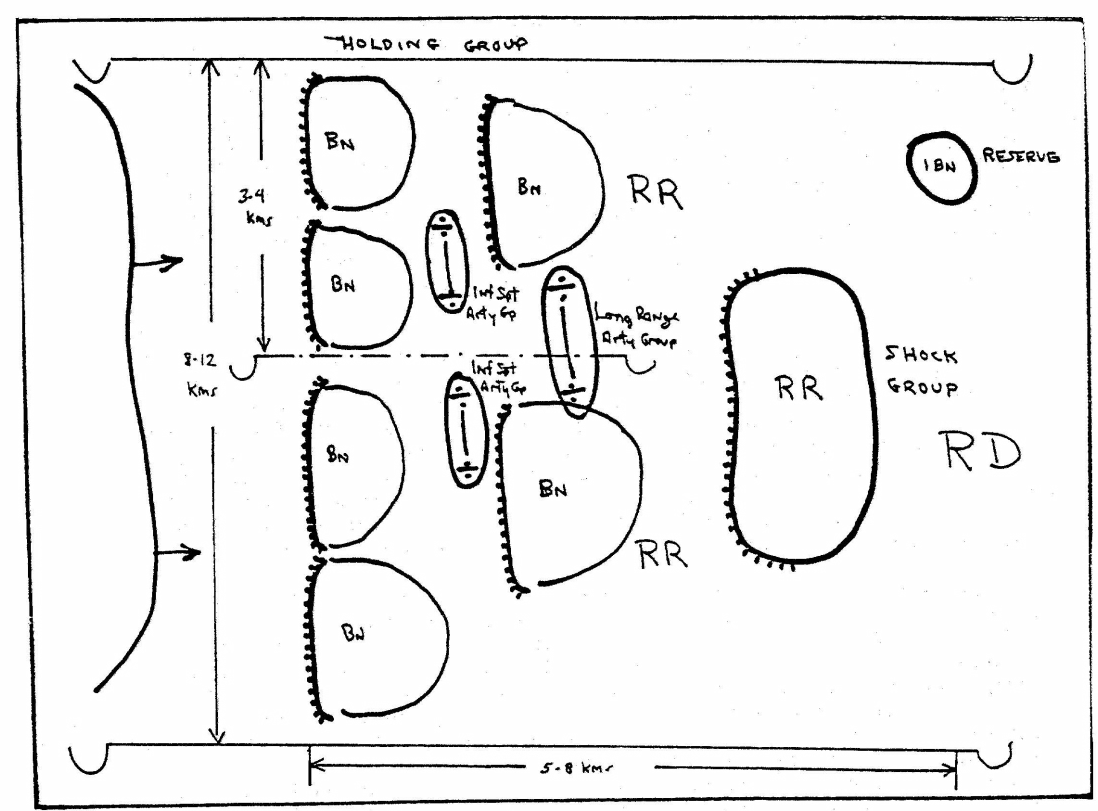

Within the context of army-level defensive operations, tactical defense in the 1930s involved the organization of covering and shock groups within rifle corps and rifle divisions (see figure l).

Figure 1. Rifle Division Combat Formation-Defense, 1930

The general neglect of defensive techniques combined with other problems to cause the disasters of June 1941. After the outbreak of war, Soviet tactics suffered from the same general malaise as strategy and operational art. Under strength rifle divisions (5,000-6,000 men) and rifle brigades (4,500 men) defended in extended sectors (14-20 kilometers) and were forced to deploy in single-echelon defensive formation with a depth of only 3 to 5 kilometers (see figure 2 and table l ). Small reserves provided little capability for sustained counterattacking, and infantry support artillery groups were weak.

The single-echelon formation was dictated by the limited forces available and wide defensive zones. This resulted in inadequate tactical densities of .5 battalions and three guns and mortars per kilometer of front.

Next page