A LSO BY G ERARD ON EILL

BLACK MASS

The True Story of an Unholy Alliance Between the FBI and the Irish Mob

(WITH D ICK L EHR)

THE UNDERBOSS

The Rise and Fall of a Mafia Family

( WITH D ICK L EHR )

Copyright 2012 by Gerard ONeill

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

ONeill, Gerard.

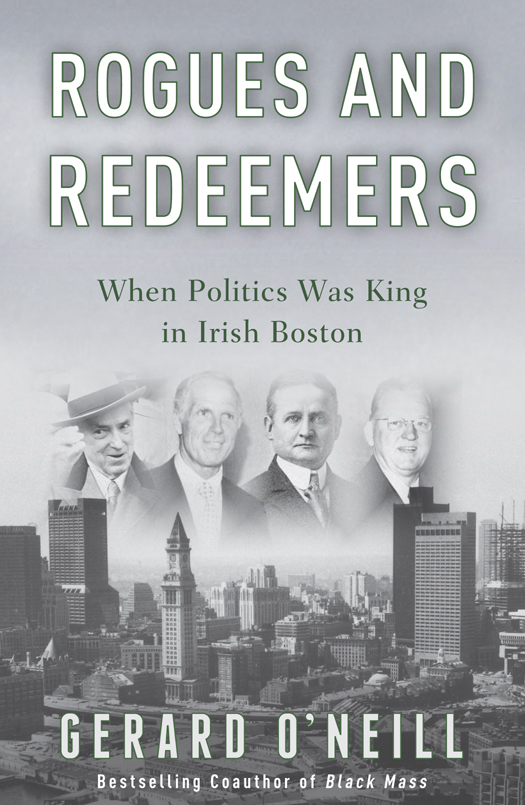

Rogues and redeemers / Gerard ONeill.1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Irish AmericansMassachusettsBostonPolitics and government. 2. PoliticiansMassachusettsBostonHistory. 3. Irish AmericansMassachusettsBostonHistory. 4. PoliticiansFamily relationshipsMassachusettsBostonHistory. 5. Political cultureMassachusettsBostonHistory. 6. Boston (Mass.)Politics and government. 7. PoliticiansMassachusettsBostonBiography. 8. Irish AmericansMassachusettsBostonBiography. 9. Boston (Mass.)Biography. I. Title.

F73.9.I6O54 2012

974.461dc22

2010053207

eISBN: 978-0-307-95279-0

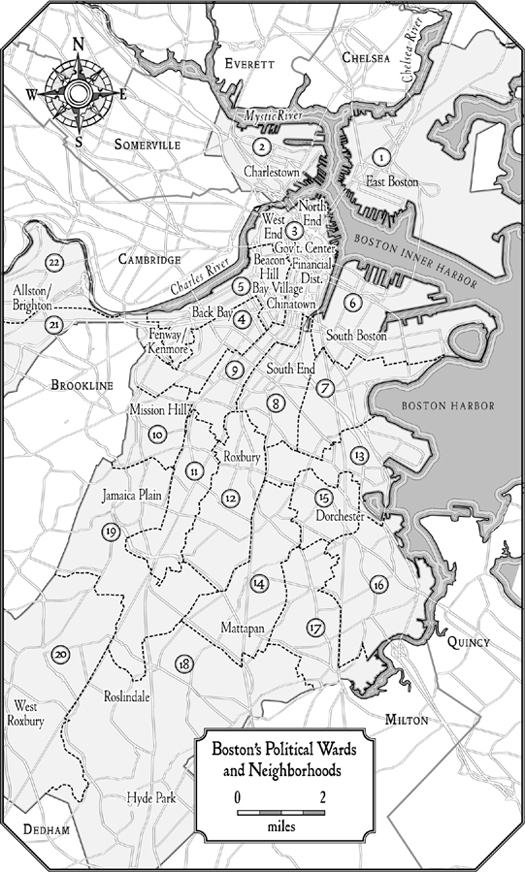

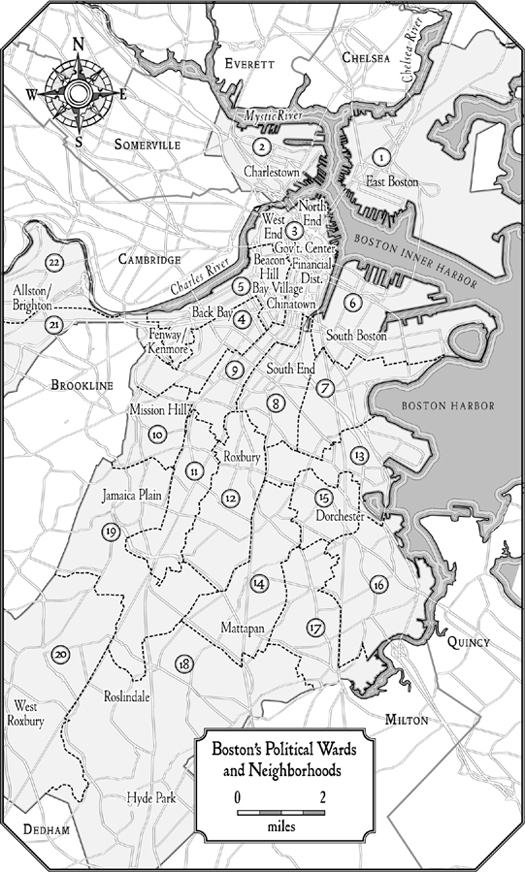

Map by Joe LeMonnier

Jacket design by Dan Rembert

Jacket photographs: skyline image, Ed Jenner/The Boston Globe via Getty Images; James M. Curley, Edison Farrand/The Boston Globe via Getty Images; Kevin White, Charles Dixon/The Boston Globe via Getty Images; John F. Fitzgerald, The Boston Globe via Getty Images; John B. Hynes, courtesy of The Boston Globe via Getty Images

v3.1

To

Charles Michael ONeill of the Beara Peninsula in Ireland, for getting us here

To

my wife Janet, Brian, Shane, Patty, Kylie, and Jack ONeill

C ONTENTS

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS

Bostons Political Wards and Neighborhoods

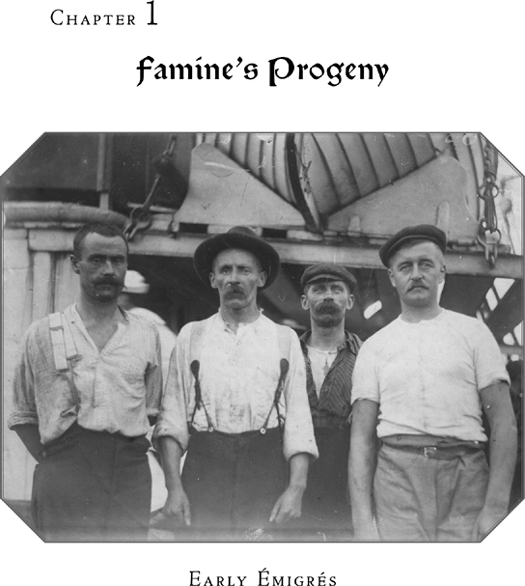

Courtesy of the trustees of the Boston Public Library, Print Department

Courtesy of the Boston Globe

F IRST there were the Know Nothings and then Thomas Fitzgerald and, soon enough, Michael Curley.

The two farmers from the west of Ireland might as well have landed on the far side of the moon as in Boston in the middle of the nineteenth century. Along the dilapidated waterfront, Boston was a hostile and miasmic place where the official government policy was to give Irish immigrants nothing and then keep them down for good measure. They had fled starvations aftermath when the lifeline potato crop turned foul back home. But they both found only squalor down the pier in an alien world.

Tom Fitzgerald bore the brunt of both ends of the journey, growing up as the oldest son on a potato farm, working the fields from the age of seven and sleeping on a mud floor in a one-room cottage on leased land. Like all Catholics in Ireland under British law, the Fitzgeralds could not vote, hold office, own land, or even go to school. He would face many of the same privations as a young man in Boston as the nativist Know Nothing Party sought to ban the Irish from voting or holding state or city jobs.

And he knew the famine all too well, struggling on his own in the boggy village of Bruff just south of the River Shannon after his mother and sisters and younger brother had emigrated. All alone, he would make a futile last stand against the blight into the 1850s before finally letting go of the exhausting rhythms of an ancient rural life.

Fitzgerald saw the worst of it and stayed until the pernicious blight had burned itself out. He was twenty-three when the fungus struck Irelands staple crop. The potato wasnt just a steady diet; it was a way of life. It was cheap as dirt, grew like wildfire, and was easy to cook. Houses were surrounded by itfields of three squares a day for man, woman, and childboiled or mashed for breakfast, lunch, and dinner, plus leftovers for the livestock. Even in normal times, the interim between the end of the winters supply and the digging for the new crop was known as Hungry July. Overlooked by history is the diversity of some Irish farms of the day, which also yielded a variety of grains as well as grazing for cows and sheep. But those crops were part of the English oppression and strictly for the export tradeeven as the tenant farmers were starving.

The emigration years unfolded with the fatal forbearance of the stoic Irish patient who endures in the belief that the malady will pass and theres no need to bother the doctor because tomorrow will surely be better. The fungus got a third of the potato crop in 1845, but the feeling was that the next year would be different. And that it wasa wipeout. Then, by 1847, the thinking was, nothing could be worse. Maybe not, but it was just as bada vicious replication that battered a moribund populace. The third year of the famine was a biblical scourge, compounded by one of the worst winters on record, with snow starting in November, followed by weeks of hard rain and icy gales. People were dying where they fell in the lanes and alleys and front yards.

An eerie pall beset the west as a gregarious people fell silent in the face of starvation and abandonment. One elderly woman wrote in a memoir about how a clamorous countryside came to a dead stop. Sport and pastimes disappeared. Poetry, music, and dancing stopped. They lost and forgot them all. The famine killed everything.

Despite several humanitarian efforts in the United States, the prostrate countryside of Ireland left the leaders of Great Britain unmoved. They downplayed the devastation as a passing pestilence and held hard to the quasi-religion of supply and demand. The export trade went on as if tens of thousands werent dying of starvation where they stood. In June 1847 the British government declared the famine over, even though it was at its zenith, shutting down its limited public works program, ending the only jobsand hopefor 700,000 Irishmen. Things were so bad that mothers and children died on the roadside after retching the grass that was left to eat. The potato plague would linger for years, and for most of those subsisting along the west coast it was emigrate or die. Tom Fitzgeralds mother and siblings joined the exodus while he stubbornly struggled on.

Even before the famine Irish arrived, Anglo-Saxon Boston was predisposed against all things Catholic and steeped in anti-papacy rhetoric that ran deep into its colonial past, a time when a woman was hanged as a witch on Boston Common for saying the rosary in Gaelic in front of a statue of Mary. After centuries of austere service to a fierce God, the natives recoiled at what they saw as the ostentatious superstition of Catholic rites. Even someone as reflective as John Adams reacted with visceral disdain when he happened upon a Mass, finding it most awful and affecting, the poor wretches, fingering their beads, chanting Latin, not a word of which they understood; their holy water; their crossing themselves perpetually; their bowing and kneeling and genuflecting.