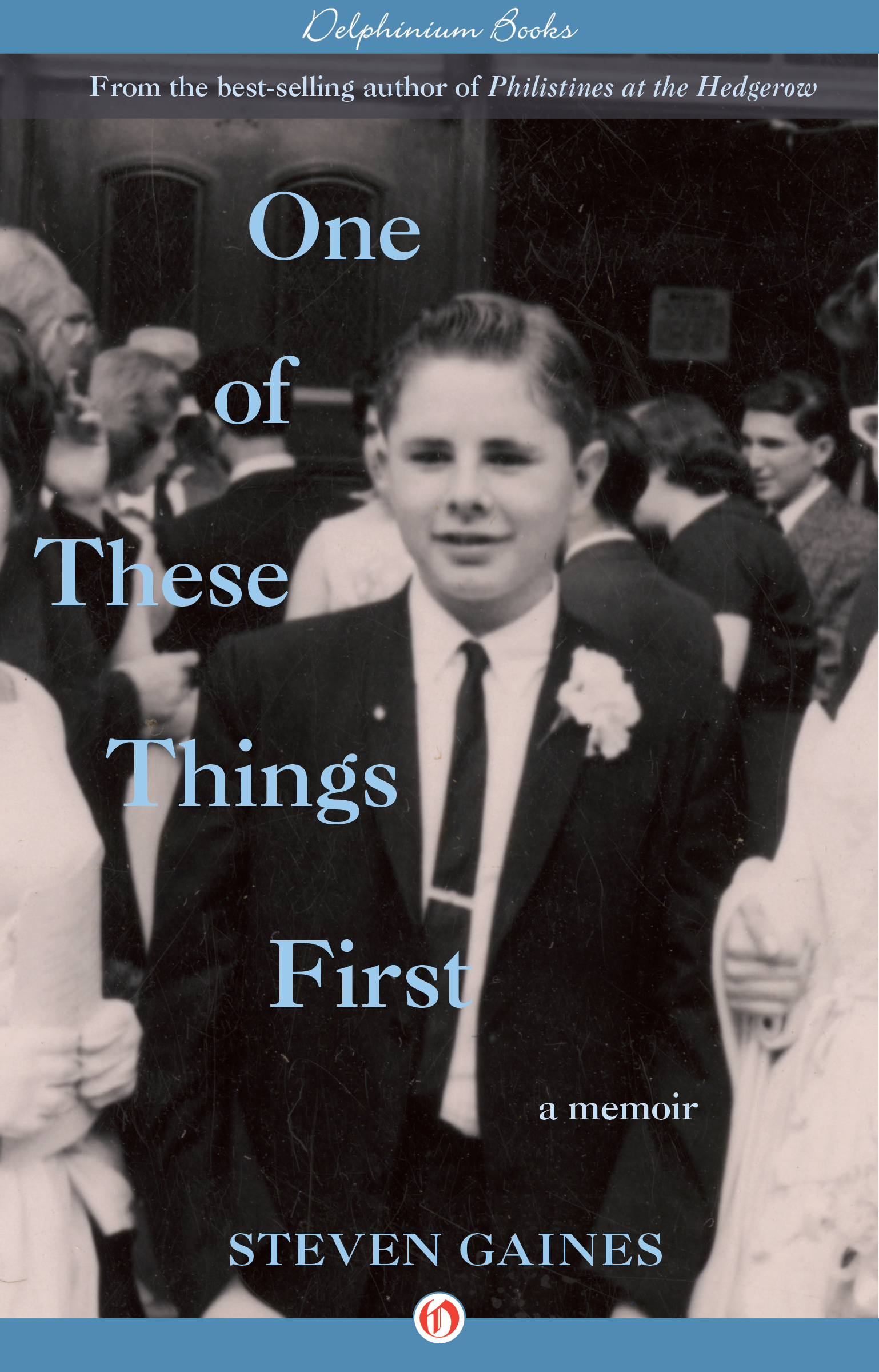

One of These Things First

Steven Gaines

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright 2016 by Steven Gaines

Cover design by Jonathan Lippincott

978-1-5040-3947-5

Delphinium Books

P.O. Box 703

Harrison, New York 10528

Distributed by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

180 Maiden Lane

New York, NY 10038

www.openroadmedia.com

For Muna and Gog

One

Lost Boy

One brilliantly cold afternoon in March of 1962, three months past my fifteenth birthday, I set out on a course of action that would shake my world from its wobbly orbit and spin it off on an unanticipated new trajectory. I managed to escape the hawk-eyed scrutiny of the three saleswomen in whose care I had been left, and slipped behind the brocaded curtain of a fitting room in the back of my grandparents ladies clothing store.

The small room was warm and close, the air thick with the cloyingly sweet smell of stale perfume and hairspray. Although only a curtain separated me from the rest of the world, I felt sealed away and safe. Of course, I wouldnt be safe for long because they would soon realize I was missing and come look for me. The saleswomen didnt like me in those fitting rooms. The saleswomen didnt like anything I did. Lily Williams said it wasnt normal for me to go into a fitting room where women got undressed, although one would think it was the most normal thing in the world for a teenage boy to be curious about a place where women were naked. But I guess maybe not those women, who were mostly overweight and middle-aged, with huge pale breasts like kneaded dough, sometimes with nipples stretched as big around as a saucer.

Those were the kind of women who came from all over the five boroughs of New York City to this Mecca of corsetry, to be fitted from the comprehensive stock of sturdy brassieres, girdles, and long-line undergarments, elaborately constructed of elastic and satin, given shape by metal stays covered by pink plush to prevent chafing. Crucial alterations were attended to while-you-wait with the unparalleled expertise of Katherine, my grandfathers chatelaine and sergeant at arms, or by my grandmother, at a black 1955 Singer sewing machine.

There was a period when, aged seven years old, almost every day I ripped open the curtain to one of the fitting rooms to reveal a bewildered, half-naked woman. Thrilled at her mortification, I shouted in my little boys voice, Oh! So sorry! I didnt know anybody was in there! and whipped the curtain closed and ran away. No matter how many times I was punished, I did it again the next day. Oh! So sorry! I didnt know anybody was in there!

That day in March 1962 I peeked through the fitting room curtain, one time, two times, and I saw that Lily and Dodie and Fat Anna were all at their stations, facing the other way, lost in their worlds. My mother had gone to pick my father up at school and take him to the accountant to do their taxes, and my grandmother was at the Culver Luncheonette for a coffee-and-English break. Everything was still; there hadnt been a customer in an hour, and the chatter had died into sleepy silence. The only sound was the febrile buzz of the fluorescent lights and the occasional hiss of a radiator. It was sunny outside, but the temperature was in the low teens, and a snowstorm two days before had left dirty drifts piled knee-high along the curb. The sidewalks were coated with ice, and the wind was so strong that people were blown slipping and sliding down the street. Some of the bigger gusts managed to move the heavy glass front door of the store inward an inch, sending up eerie howls of cold air, rushing in like spirits from the street.

Lily Williams was at her usual place, sitting in a bentwood chair midway up between two display cabinets, reading the World Telegram . One day when I was hiding in a corrugated box, eavesdropping, I heard Lily say to my grandmother, Nothing good will come of him being in those fitting rooms. Lily Williamss refrain was that anything I did would come to no good. I would come to no good. It was drummed into me that I had to be nice to the saleswomen, even if they predicted I would come to no good, because they worked for free. They came to be part of Roses Bras Girdles Sportswear as though they had joined the Foreign Legion, to escape another life, bored and lonely at home. They even wore a kind of uniformsmocks in bright floral prints with patch pockets, purchased at the corner smock and robe store on East 2nd Street, for six dollars each.

I didnt know how Lily Williams knew to tell my grandmother I would come to no good, because she didnt have any children herself, or even nieces and nephews. She was tough old shanty Irish, a weedy, little thing, maybe ninety-five pounds, with a thin face and wavy white hair pinned up behind her head. She earned extra money fabricating flowers out of gossamer petals of silk for a Manhattan milliner. Sometimes she let me help her wire the flowers to their stems. One day, when I was eleven years old, Lily stopped talking to me because I was fresh to her. I never realized before that someone could ignore you, as if you didnt exist anymore, even if you spoke to them; they would look the other way or through you.

Dodie Berkowitz was leaning back on the lingerie counter, a string bean with a small belly, chain-smoking Parliaments, holding her cigarettes pointed up in the air like a stick of chalk. She had pretty green eyes, but she was pockmarked, slow to smile, and dour, always tattling on me to Katherine.

My only saleslady friend, Fat Anna, was doing the Crostix behind the sewing machine. She regularly wore the black raiment of an Italian widow, although her husband, a plumber named Angelo, was alive and well. She hugged me with her hammy arms when she saw me, and gave the top of my head a kiss. She said novenas for me at church, and it made me feel important that anyone was praying for me. Fat Anna was the only one who would care. The others would be secretly glad, their faces set in deep satisfaction that they had been right all alongI had come to no good.

I stepped back and considered myself in the mirror. No strapping high school freshman here. I was pale and pudgy, and I had tortured my mess of wavy strawberry blond hair into a perfect inch-high pompadour, hardened in place with thick white hair cream, like plaster of Paris. I had meticulously doctored an inflamed whitehead under my bottom lip with Clearasil, so I wouldnt be embarrassed when they found me. I was also spiffed up for the occasion, new clothes, slacks and sweater in shades of forest green, the big retail color of the season.

I moved closer to my reflection until my breath condensed on the glass and I tasted it with my tongue, one lick, two licks, cold and salty, and I concentrated deeply into the eyes of the boy in the mirror and tried to will another boy out of me, like the spirits that stepped out of dead bodies in the movies, only this boy would tell me if I could grow up, or maybe it was the boy who was pushing the lawnmower in Lynbrook who would grow up for me. Maybe I had the whole thing backwards, maybe I should go into the mirror, and then I would be him.