PART 1

Acknowledgements

I wish to acknowledge and thank very sincerely the people who have helped me on my spiritual journey. Peggy Wolstenholme, my teacher and guide; and Thalia Lichtenstein, who was with me at all times as I began my channelling. The first people who came to the group each week and asked questionsJudy Greig, Sue Everett, Derek Viner and my sister Diane Hall. Each week Diane faithfully recorded and transcribed the sessions. She gave each person present a copy of the questions and answers. This has enabled us to have a record of all the teachings over the years. My astrology teacher Brian Clark, who led the trips to Greece, and who has helped and advised me. My editor Christine Gillespie, who was an invaluable guide; and Frith Luton, also a group member, who suggested I write this book. All the people who came each week over the years bravely asking some very personal questions, seeking guidance. I sincerely thank each person and hope these teachings continue to bring help and guidance to all who read them. Some personal names in this book have been changed.

I wish to dedicate this book to my grandfather William Ames Ramsden (28 October 1864 21 October 1937) who first taught me about reincarnation.

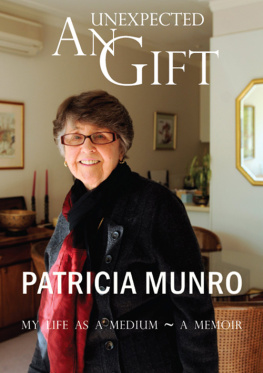

PATRICIA MUNRONovember 2011

1

TO START at the very beginning we go back to the early 1930s in Melbourne to the time of the Great Depression. My parents had been married only ten months before my birth. They bought a home in Fairfield, at that time almost an outer suburb of Melbourne.

They had met at work, both in the same factory in the leather trade. My father had migrated from England to Australia in the early 1920s, and with his qualifications as a glove maker, he immediately found a job. My mothers father was in the same industry as a boot manufacturer, and my mother and some of her sisters also worked in the leather trade.

My father had shown he was very attracted to my mother but she was not at all interested in him. She was a very attractive woman and already had a steady boyfriend with prospects, the person she expected to marry. Most unexpectedly her boyfriend met another woman and in a very short time broke off his long term relationship with my mother. My mother was shocked and angry but also very upset. She was already twenty-six, considered getting old in those times, and she did not want people to feel sorry for her. She was an extremely proud woman, who hated people knowing she had been jilted (her words). To save face she agreed to marry my father.

It wasnt exactly the recipe for a happy marriage, and my earliest memories are of them constantly fighting. However, my birth did forge a bond between them for they both loved me very much. My mother wanted a home birth and there was a midwife to assist. It was a normal birth and she was already in labour when my father left for work. He decided to ride his bike home from the factory at morning tea time and was there just after I was born. My birth also brought them some good luck. The Melbourne Cup was run about a week after my birth. I had entered the world with white spots all over my nose. There was a horse running in the Cup named White Nose, so they backed this horse and it won.

My mother was born in Melbourne. She was the third youngest of ten children who all came into the world two years apart. There were four boys, then a girl, followed by another boy and then four girls. They were all well educated for the time. One of her brothers died of the flu at the age of twenty-one, the other four became very successful businessmen. They were also a very sporting family, with two brothers representing Australia in Paris in the 1924 Olympic Games as bike riders, and my mother was in the Victorian State Womens Cricket Team.

My mothers father was of English/Irish descent, and her mother of German background. He was wealthy and owned a successful boot manufacturing business in Clifton Hill. But, like many others, he lost a lot of money in the Depression.

These times were very difficult for everybody, my parents included. Both had lost their jobs at Matears, a factory that made leather goods, and they were unable to find other work apart from door-to- door selling. My father purchased some hides of leather, which he cut into six pairs of gloves, and my mother machined them in the lounge room of his rented home. To save the three penny tram fare my father, then aged twenty four, walked from his home in Fitzroy to the city. He sold the six pairs of gloves to the buyer at Foy and Gibsons department store. That was the beginning of his glove-making business, which was up and running by the time I was born. It grew into a successful and profitable company, also making leather jackets. It lasted until he retired at the age of seventy-two, nearly fifty years later.

My father was born in 1905 near the village of Montecute in Somerset, England, the youngest in the family. His father was a shepherd and had several children by his first wife who died young. He married again, and his next wife was my fathers mother. She signed her name on his birth certificate with a cross. His mother died when he was three. My father never spoke of his own father. We gathered that he hated him.

My father left school at the age of thirteen, very early by todays standards. It was during World War One, when most of the men had gone off to fight. He earned pocket money by looking after other peoples chickens, a job which he loved to do. Being a natural businessman, Dad quickly discovered that by removing fertile eggs from his clients chicken pens and hatching them with his own broody hens he could make a mans wage selling eggs from his own chickens at a time when food was scarce and eggs were considered luxuries. From that time onwards he always kept chickens at his home.

His memories of that time turned him off war forever. He would recall watching the recruiting teams come to his village with the band playing and the banners waving and the women cheering to encourage the young men to sign up for the army. He would say there were no bands, no banners and no cheering when the hospital trains came into the village station a few weeks later with limbless and shell-shocked, shattered men, victims of the butchery of the trenches.

My fathers first real job was as a blacksmiths apprentice where he stoked the anvil furnace as well as fetching and carrying outside. This work did not last beyond the first winter as he became very ill with the flu and nearly died. Fortunately, one of the customers in his egg business was foreman at a nearby glove factory and managed to get him an apprenticeship as a glove maker, which meant he could work inside and not in the snow. As soon as he finished his apprenticeship he set off for Australia having decided to get as far away from his own father as possible.

Dad arrived in Australia by himself on the 1st of January, 1924 at the age of 19 with three pounds to his name. He found lodgings and the job with Matears in North Fitzroy where he met my mother. Later, her family became his family, although many many years later, he returned to England for a brief visit to see the sisters who had reared him after his mother died. He also had me send them money from him in later times.

By the time I was born in 1931 Dad had relocated the glove business from the front room of the rented house in Fitzroy to a factory near the Clifton Hill station owned by Uncle Dickie, my mothers eldest brother. Uncle Dickie was a colourful character. He had owned two shoe factories and two shoe shops in Melbourne at the beginning of the Depression and nearly lost them all when the bank called in his mortgage debt in 1930. It was my father who helped by lending him enough money to satisfy the bank, even though my father had only been in business for a few years. Uncle Dickie never married but had a succession of mistresses whom he set up in various single fronted terrace houses around Collingwood and Clifton Hill. He bought the houses for cash from money skimmed from his various businesses. Each new mistress meant a new house until he had seven or eight. He was too kind hearted to throw them out when he tired of them. In the latter part of his life, Dad would drive Uncle Dickie around to collect the rent from his tenants, the mistresses having long passed on. It was a sad day when he died. We were shocked to learn that the titles to all his houses were in bogus names and never formed part of his estate.