Osprey Games, an imprint of Osprey Publishing Ltd

c/o Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

Or

c/o Bloomsbury Publishing Inc.

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018

E-mail:

www.ospreygames.co.uk

This electronic edition published in 2017 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

OSPREY and OSPREY GAMES are trademarks of Osprey Publishing Ltd, a division of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Warlord Games

The Howitt Wing, Lenton Business Centre, Lenton Boulevard, Nottingham, NG7 2BY, UK

E-mail:

For more information on Bolt Action and other products, please visit www.warlordgames.com

First published in Great Britain in 2017

2017 Osprey Publishing Ltd and Warlord Games

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1792-1 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1794-5 (eBook)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-1793-8 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2384-7 (XML)

Editors Note

For ease of comparison please refer to the following conversion table:

1 mile = 1.6km

1yd = 0.9m

1ft = 0.3m

1in = 2.54cm/25.4mm

1 gallon (Imperial) = 4.5 litres

1lb = 0.45kg

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations are being spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

CONTENTS

In June 1944 the Axis powers in Europe were about to be subjected to two major hammer blows. In the West, the final preparations were being made for Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Western Europe. In the East, the Red Army was planning a massive offensive, with bold objectives to critically damage the German Army and eject it entirely from the Soviet Union and, by pushing deep into Poland, providing the springboard for later offensives that would eventually find the Red Army in the streets of Berlin ushering in the final collapse of Hitlers Third Reich. The war in the East was now in its third year and the writing was on the wall for Germany. To a large extent, the course of the war on the Eastern Front in its first year and a half had been a catalogue of crushing German victories over their Red Army foes. Since the opening of Operation Barbarossa in May 1941, the Wehrmacht had advanced deep into the territory of the Soviet Union, had briefly been at the gates of Moscow, and at the end of 1942 was besieging the two major city bastions of the Soviet north and south, Leningrad and Stalingrad. Despite the rebuttal at the gates of Moscow (due as much to the harsh winter conditions as the brave and solid defence of the Red Army) it seemed to many neutral observers that the defeat and collapse of the Soviet Union was inevitable. Yet, within six months, conditions had decisively and irrevocably changed.

In February 1943, the shattering defeat at Stalingrad and the virtual annihilation of the 6th Army, which at that point had been the largest organised formation in the Wehrmacht, had enormous impacts on the armies of both sides. For the Germans a sense of fatalism began to grow, whilst amongst the Soviets spirits rose. After the months of crushing defeats, encirclements and mass capitulations, the Germans were finally revealed to be beatable and their aura of invincibility had finally been ripped aside. This is well illustrated by a common story from the end of the Stalingrad operations where Soviet troops harassing sullen German prisoners, pointed at the remains of the devastated city and screamed that it would only be a matter of time before Berlin resembled the ruins of Stalingrad.

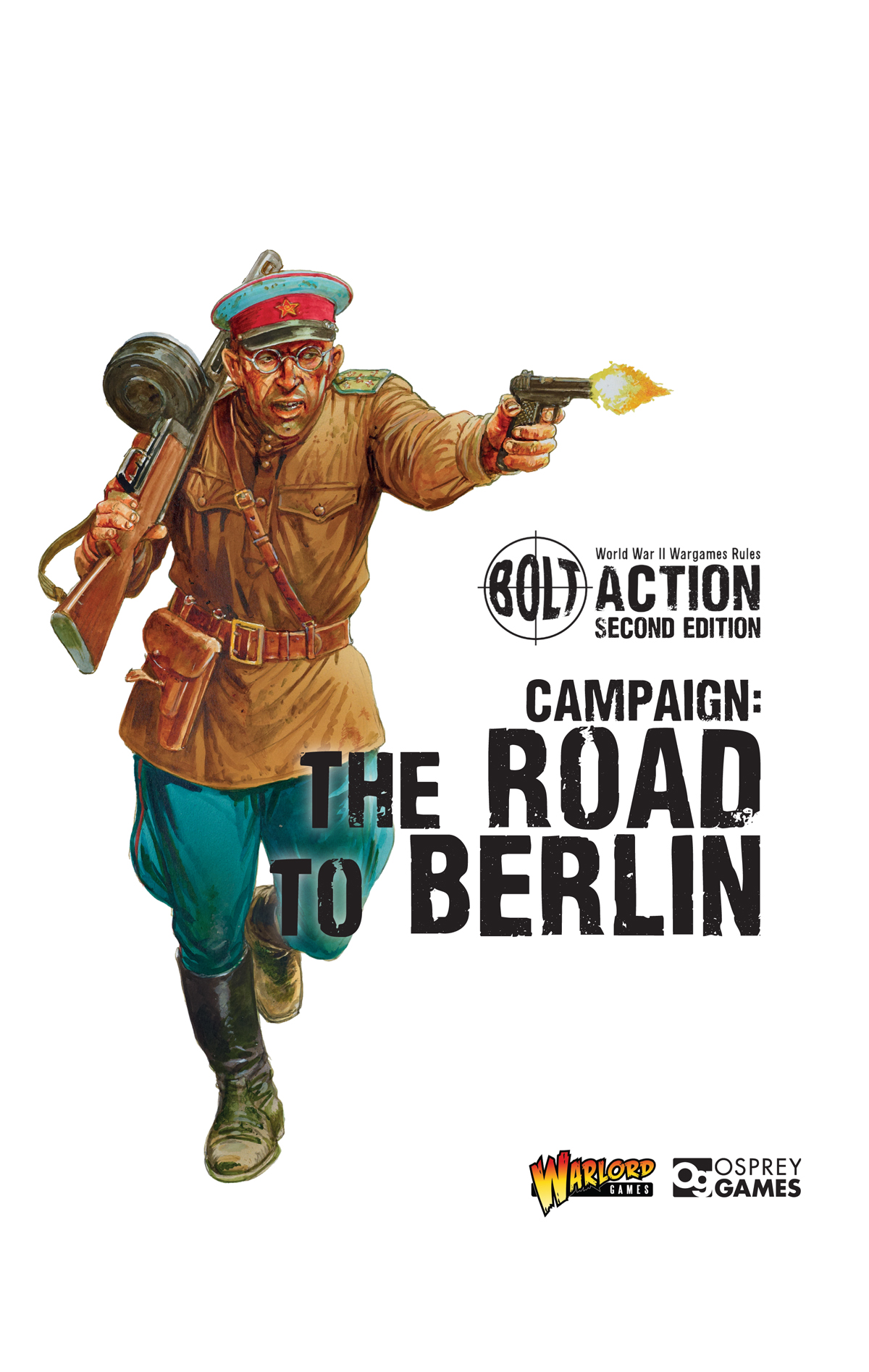

Soviet Assault Engineer Squad

1943 also featured Operation Zitadelle, with the Battle of Kursk probably representing the last chance for Germany to regain the initiative by obtaining a victory on a massive scale and destroying a large part of the Red Army. The to and fro nature of the summer 1943 campaigns resulted in many gains and losses for both sides but crucially saw the creation of a large salient or bulge of Soviet forces centred on the city of Kursk. Whilst a potential jumping off point for a new Soviet offensive, it was also viewed as a golden opportunity by German strategists bringing back halcyon memories of the successful 1941 and 1942 offensives. Armoured assaults from the north and south of the salient could trap hundreds of thousands of Soviet troops and tanks. Whilst perhaps not winning the war in the East, it promised to delay future Soviet offensives for at least a year. On the contrary, Kursk and its aftermath were to prove that everything had changed and German prospects on the Eastern Front were dire and in all probability terminal.

The Soviet army of 1943 was not the same as that had faced the Barbarossa invasion of two years before. It was led by competent, and in many case exceptional, officers at all levels from junior unit leaders all the way up to marshals of the Red Army. These men had learned their art in the heat of battle. The incompetent survivors of the 1930s political purges had been weeded out either lying dead on the battlefield, or residing in German POW camps. Soviet head of state and, technically, Commander of the Red Army Josef Stalin had also finally understood that he need not interfere in every single military decision. Constantly paranoid of a challenge from his senior officers, he had orchestrated some of the worst military setbacks of the Red Army in the early months of the campaign with demands of no retreat even when his few able generals were telling him otherwise.

Exceptional generals such as Zhukov, Konev and Rokossovsky flourished and proved themselves easily the equal of their German counterparts. They had closely studied German strategic and operational tactics at very close range and had learned to not only counter them but, far more importantly, to anticipate them.

By the time of the Kursk operation the Soviet High command the STAVKA knew exactly what the Germans were planning and formulated a strategy to both blunt the offensive and launch a series of follow-on counter-attacks.

When the German attack finally fell on the salient, their carefully marshalled concentrations of armour many of which were the new and effective Tigers and Panthers did not find themselves fighting inferior Soviet armour, but rather dug-in infantry supported by huge numbers of artillery and dedicated anti-tank guns on a battlefield liberally sown with huge minefields and anti-tank traps.