Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

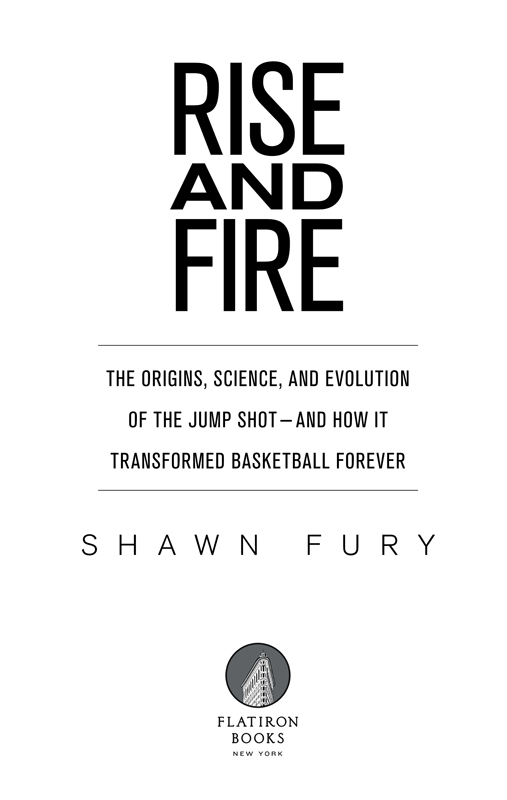

FOR MY DAD, PAT FURY, WHO NEVER LET ME WIN BUT TAUGHT ME THE JUMP SHOT THAT FINALLY HELPED ME BEAT HIM. AND FOR MY MOM, CEES FURY, WHO STILL THINKS EVERY SHOT I TAKE WILL FIND NOTHING BUT NET.

New York Citys Inwood Hill Park covers 196 acres on the northern tip of Manhattan, about twenty-five minutes on the subway from Times Square. Visitors roam Manhattans largest remaining ancient forest in this park, a green paradise unlike any other place in the city, home to springs, swans, rock caves, salt marshes, and, some longtime residents say, ghosts. In 1626, Dutchman Peter Minuit bought Manhattan Island from Native Americans. A plaque in the park marks the supposed and disputed location of the infamous real estate transaction. In the middle section of Inwood Hill Park, tucked next to the baseball diamonds and the tennis courts, youll find one of the citys hundreds of outdoor basketball courts, home to thrilling full-court five-on-five showdowns between superb young athletes and hard-to-watch half-court one-on-one battles between middle-age teachers who are one torn ligament away from permanent retirement.

The Inwood Hill Park court has never been one of New York Citys famous playground venues, like Rucker Park or the Cage at West 4th Street, courts that earn headlines and make or ruin reputations. Filmmakers havent created documentaries focused on Inwood Hill Parks players or games. The court isnt even the most famous playground in the area. About ten blocks away, in Monsignor Kett Playground, the court thats commonly called Dyckman Park attracts some of the top players in the city during an annual summer tournament and boasts a bit of historical heftKareem Abdul-Jabbar grew up in the area and played there when he was a kid and still went by the name Lew Alcindor. I live five minutes from Inwood Hill Park, and on a 73-degree September day the court remains the perfect spot for a thirty-eight-year-old has-been with no quickness who still loves the game and, above all, still loves to shoot. City schools are in session so the court sits empty when I arrive just past noon. I remove my sweatshirt, perform a cursory leg stretch, pull my $22 Target ball out of my duffel bag, test it with three dribbles, palm it in case this is the day I throw down the first one-handed dunk of my life, and walk toward one of the courts four baskets. Two of them have nets, two of em dontand nobody voluntarily shoots on one without the cords.

Out on the court, Im a bit uneasy in my elements, at times feeling out of place as I shoot alone. No one looks twice at an out-of-shape forty-year-old man in tan shorts who strikes a solitary figure on a driving range, pounding away on a bucket of balls with the driver he received for Christmas. But how many times do you see an adult alone in a public park at a basket, shooting some hoops for the hell of it? In the suburban backyard, on the basket he constructed out of love for his three kids? Sure. At the YMCA as he waits for the other goggles-wearing, knee-brace-sporting, noon-hour warriors to arrive? Of course. But it feels a bit strange to perform as a solo act on an outdoor court, taking four dribbles before every free throw and firing 23-footers from behind the three-point line.

Im here for the exercise. Running for runnings sake has always seemed like a punishment and holds no appeal for me. Chasing after an errant shot remains more enjoyable than pedaling on a stationary bike. Mostly Im here because I love the game. And theres nothing I love more about basketball than the jump shot. When kids pick up a basketball, the first thing they do is throw it in the air. They fire a shot, often before they dribble. Even if its on a Nerf hoop, anyone with a ball and a target wants to shoot. Growing up in Minnesota, I learned to shoot on a hoop attached to my neighbors garage and in my small towns park, on a basket six inches too high. I spent countless hours playing on those baskets and hundreds more shooting at my grandpas farm, drilling jumpers on the basket my dad and his brothers attached to a white barn decades earlier. In the winter I would wear two pairs of glovesthin ones I called my shooting glovesand shovel snow off of the city parks concrete court in zero-degree Minnesota weather, all so I could practice my shot. Throughout those years I probably won a thousand imaginary NBA titles and a hundred fictional high school state championships with my jump shot. At first, like everyone who starts shooting as a kid, before I developed the consistent form and performance that comes with age and height, I shot from the hip, heaving the ball instead of shooting with proper mechanics, hoping and praying for good results instead of expecting them. As I grew and matured and learned to shoot from above my head while leaving the groundthe coordinated actions finally creating a fundamentally sound and effective formthe jump shot became my first love during my days playing high school and college ball.

And now, out at this New York City park, as I self-consciously jog after shots that bounce off the rim and roll to the far side of the court, I find a rhythm. Starting with little four-foot bank shots, I follow with free throw line jumpers. Dribble out and launch threes from the baseline. Head to the top of the key for a straight-on three. Come off the dribble for a 15-foot pull-up jumper. Now do it while dribbling to the left. Hope that no ones watching. Ignore them if they are. Because today, roughly thirty-four years after I first picked up a ball, theres still nothing like being on a courtinside or outside, with teammates or alonefiring away with the jumper.

Rise and Fire celebrates the jump shot, examines its origins, explores its fundamentals, and honors those who dominated the game with it. Consider it a love letter to basketball and the jump shot, and a profile of how it changed the game. The jumper remains the most important play in basketball. When the first jump shooting pioneers introduced the shot, it changed the sport. Experts still debate who invented the jumper. No single correct answer exists. But no one debates the impact the shot had on the sport. Players no longer found themselves earthbound. Defenses controlled the game in the early years, or, perhaps more accurately, subpar offense ruled. To adapt, players jumped to get their shots over the raised hands of defenders, and at the same time rose above the games conventions. Basketball was never the same. The jump shot created offense, excitement, fans, and legends. Games that formerly ended with scores fit for a football field soon saw both teams reach triple figures.

In the decades since, the jumper expanded its dominance, becoming the most prevalent shot, the toughest to perfect, and the most important to master. Basketball styles change, and the jumper has always led the charge. It increased scoring in the 1950s. Great guards used it to win titles for and against great big men in the 60s. High-scoring gunners shot their way to absurd numbers in the 1970s. The midrange dominated the 80s. And today the three-pointer dictates pace and strategy, as even the games big men gravitate farther away from the basket. No one knew what to make of the jumper when it first arrived, and the same was true for the three-pointer. But eventually people saw the power in both.