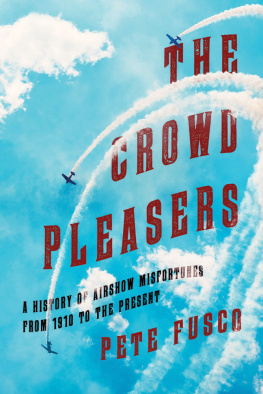

Copyright 2018 by Pete Fusco

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

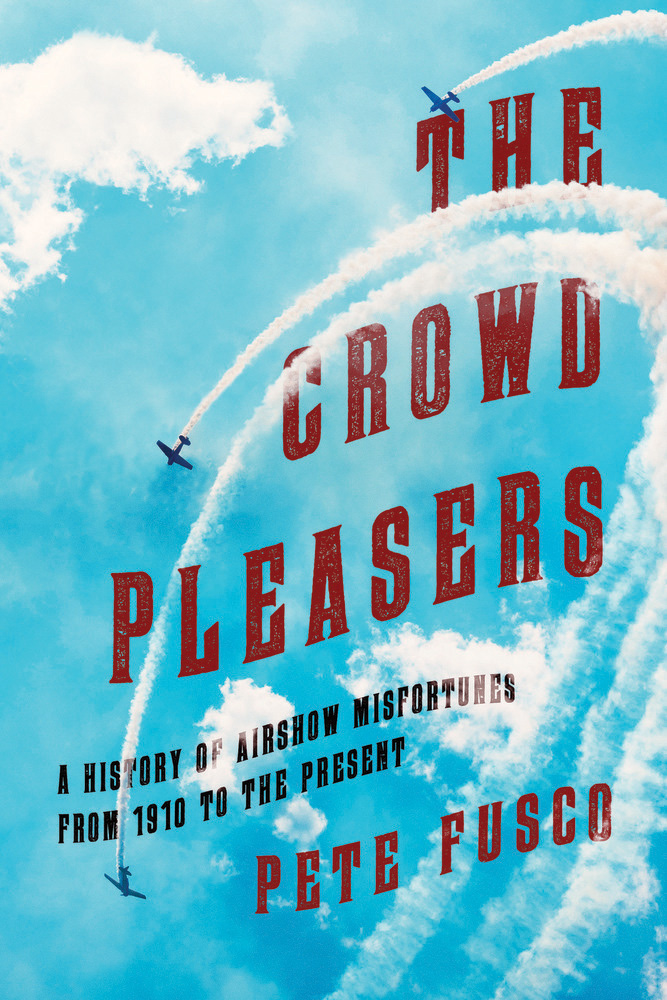

Cover design by Rain Saukas

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2818-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2820-2

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to Madeline Davis, one of many crowd pleasers who took the risks while the rest of us watched.

Life is being on the wire, everything else is just waiting.

KARL WALLENDA

INTRODUCTION

BEFORE I could begin writing this book, I had to convince myself that the performers who died over the last hundred years while pleasing a crowd wanted to be remembered. I kept my nerve and listened as I did the research, which was a gloomy walk at night through an old cemetery full of voices. Some of the departed whispered but most screamed at me to tell their storiesnot to vindicate nor mourn nor rehash the gruesome detailsbut simply to acknowledge the humanity. It was all I needed to hear . In return , I promised them that their book would not be a catalog of tragedy; a heavy hand was out of the question. The stories required, no, demanded , a special touch focused on life, not death, although I would have to find meaning in both.

I must confess to the crime of beginning this book with a faulty premise: That the common thread among airshow performers was a need for excitement and income. It soon became clear that motivations ran deeper than kicks and money, far deeper, something akin to that of the scrappy mortals of Greek mythology prone to picking fights with insurmountable forces. When taking chances, the ancient Greeks sought the favor and protection of Tyche, their goddess of risk. She was blindfolded and, as if to accommodate the future, winged.

It helped me understand why someone who could not swim would attempt the first takeoff from a ship with a large crowd present, or jump out of an airplane wearing a parachute over a straightjacket with the ripcord in his mouth, or do handstands on the upper wing of a Curtiss Jenny a thousand feet in the air, or round a pylon at 500 miles per hour fifty feet off the ground, or fly into a building for the movie cameras, or stand a twenty-ton jet fighter on its tail and hover in front of the grandstand, and much, much more.

The Crowd Pleasers is a distillation of many different, oftentimes contradictory, sources. The selected events represent a cross-section of airshow and stunt-flying misfortune spanning a century. Each segment stands alone but, taken together, form a cumulative tale of uncommon men and women whose lives, though in many cases shortened by tragedy, were lived far more fully than most.

Several individuals in the airshow business, however tangentially, suggested that the history of airshow accidents was best left entombed or, at the very least, heavily airbrushed. Its perhaps why a book such as mine has never been written. Quarantined history, of airshows or anything else, benefits no one. The past begs to be remembered. The future depends on it.

The Crowd Pleasers begins in 1910, when all flights were airshows. Attracting spectators was no problem; getting them to pay was the trick. Crowds, then as now, became easily jaded. Straight and level flight and a simple circuit of the field did not sell tickets. But folks lined up, money in hand, to marvel and cringe at a dive of death. Risk is a commodity always in demand and flying was mans riskiest endeavor since the day sailors first left the sight of land.

From the start, the exhibition pilots, as they were then known, stood out from the rest. Everything they did and still do requires exceptional ability, a commitment to practice and a risk threshold unimaginable to most pilots. Those pilotslike this authorwho spent much of their flying careers in Boeings drinking coffee, reading newspapers, annoying flight attendants, and watching the world below from a safe distance, find even the most modest Sunday airshow performance not only impressive but, if theyre honest, intimidating. Some of us may have taken an occasional chance for the hell of it but we certainly didnt do it every weekend.

I learned many curious facts writing this book. For instance, aircraft crashes were not referred to as crashes in the early days. Aircraft did not begin to crash, in written accounts at least, until well into the 1930s. Early aircraft that did anything other than land or alight successfully were typically described as having fallen from the sky, with the results left mostly to the imagination.

And though exhibition aircraft fell from the sky with alarming frequency in the early years, the incidents were not overly scrutinized and their causes seldom determined. Blame was almost never assigned. An aircraft fell and the pilot was injured or killed: End of story. Journalists of the day seemed to place the business of exhibition flying in the same category as climbing mountains without a rope. Their euphemistic use of fell suggested a randomness, even a blameless unpredictability, almost as if the first reporters of airshow accidents attempted to give dead performers the benefit of the doubt.

That all ended when the federal government took over in the late 1920s. By 1938, the government had institutionalized aviation in the United States and enacted rules that greatly limited the scope of aerial entertainment. The term crash, with its implications of ineptness and recklessness, came into wide use about the same time. Laws were passed which, in certain cases, made crashing an airplane illegal, a crime to this day. And, by god, someone would pay, if only with the pitiless and vindictive bureaucratic tagline PILOT ERROR stamped on his or her record. Permit me to digress further with a cheap shot at the television network ghouls that pass themselves off as aviation experts. Though usually well out of their depth, they eagerly analyze an airshow accident with only a few minutes notice, as convinced of their divine infallibility as a fifteenth-century pope.

I was once part of that media. During a lull in a checkered flying career, I worked as a reporter for a major metropolitan daily newspaper and know the first rule: Most news is only news for a day, usually just a few hours. The Crowd Pleasers picks up where the scant media coverage of airshow accidents ends. With full disclosure of my limitations as a pilot who loves to watch but not do snap rolls, I placed a thumb on the pulse of airshow history and recorded my findings as intelligently and compassionately as possible. I resisted opinions, even though at times my senses were numbed by what seemed to be unwarranted risk and preventable death. I made no effort, however, to hide my awe and envy of the performers who took and still take those risks.

Next page