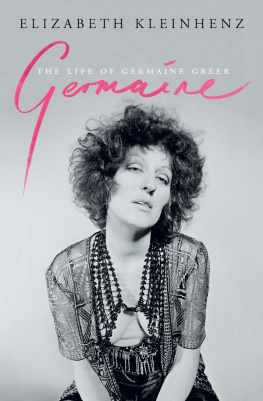

GERMAINE

Elizabeth Kleinhenz was born in Melbourne, and was until her recent retirement a senior research fellow at the Australian Council for Educational Research. She is also the author of A Brimming Cup: the Life of Kathleen Fitzpatrick .

Scribe Publications

2 John St, Clerkenwell, London, WC1N 2ES, United Kingdom

3754 Pleasant Ave, Suite 100, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55409, USA

1820 Edward St, Brunswick, Victoria 3056, Australia

Published by Scribe 2018

Copyright Elizabeth Kleinhenz 2018

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publishers of this book.

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Every effort has been made to acknowledge and contact the copyright holders for permission to reproduce material contained in this book. Any copyright holders who have been inadvertently omitted from the acknowledgements and credits should contact the publisher so that omissions may be rectified in subsequent editions.

9781911617914 (UK edition)

9781947534780 (US edition)

9781925693560 (e-book)

CiP records for this title are available from the British Library.

scribepublications.co.uk

scribepublications.com

For Emily, Isobel, Jake, Ava and Dan

Contents

Introduction

Brave woman!

How often have I heard those words spoken by people who have discovered that I am writing a biography of Germaine Greer. They are speaking not of her, but of me.

I am not especially brave, but nor am I afraid of Germaine Greer. Well, maybe just a little bit. In 2015, when I embarked on the project, my knowledge of her personal life was sketchy. I did not know how opposed she was to the idea of anyone writing a biography of her. She had sold her archive to the University of Melbourne by that time, and it seemed reasonable even obvious to me that the archive should be used as a biographical source. I had read and enjoyed Christine Wallaces 1997 biography Untamed Shrew , but it was not until I was well advanced into my research that I discovered the full extent of Greers opposition to that book, and was shocked by her venomous attacks on its author. By then I had found a publisher and it was too late to go back. Not that I would have anyway, for Germaines life was proving much too interesting.

Before I started work on the biography I wrote politely to Greer, telling her that I was planning to study her archive and asking her if she had any preferences as to how it might be explored by researchers such as myself. I addressed her as Dr Greer. She responded coldly rudely, actually that it was not up to her but to the university, who now owned the archive, to decide how it should be used. She would not interfere, she wrote, but nor would she assist me in any way. Finally, she admonished me for failing to get her title right. She was Professor, not Dr.

In February 2018, she wrote to me again, addressing me as Mrs Kleinhenz, knowing full well that my title is Dr. Oh Ger maine , I sighed.

I first heard the name Germaine in 1959, when I was a student at the Toorak Teachers College in Melbourne. I had become friends with a group of girls who had been at school with Germaine Greer at the Star of the Sea convent in nearby Gardenvale. They, like me, were two or three years younger than she was and they spoke of her often with a kind of reverence that annoyed me. It was: Germaine would have something to say about this or Germaine would never agree with that, or simply, with eyes raised adoringly to the heavens, Oh Ger maine ! We were all still into our religion at that time, and some of those Star girls had concerns about this Germaine persons soul. She could be such a force for good, Oh, Im sure she would never give up her faith... So the conversations went. I was bored and began to conceive a mild dislike for this distant, unknown figure. Why should she be any different from the rest of us?

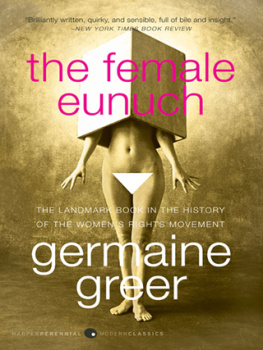

It would be another ten years before I found out just how different she was. I had gone on from teachers college to Melbourne University, started on a career as an English teacher at Melbournes top government girls secondary school, got married, had a baby, stopped work, was living in a raw new house in a raw new suburb and was getting used to being called Missus or Mum by the men who delivered the bread and groceries, or tried to sell me a vacuum cleaner. All should have been well I was doing exactly what I was expected to do but something, something major, was wrong. In 1971 I read The Female Eunuch and I began to understand. Urged on by my mother, who turned out to be an unlikely feminist of the first wave, I went back to work and bought a car. I think youve become a womens libber, my brother-in-law accused. And you, I replied tartly, igniting a family feud that did not heal for years, are a male chauvinist pig.

Who was this Germaine Greer, who changed my life and the lives of millions across the world in the middle years of thetwentieth century? She was born on a hot Melbourne day, 29 January 1939, as some of the bushfires of Black Friday on 13 January the worst in Victorias history were still burning around the city. Her mother, Peg, was a housewife; her father, Reg, sold advertising space in a newspaper. Her parents marriage was not happy and the situation in the Greer household worsened after Reg came back from the Second World War. Over the years, the familys economic situation improved somewhat, two more children were born and the Greers moved into larger houses, but there were few books and little conversation. Ultimately, the levels of dullness and cultural deprivation, together with a jumble of unresolved family tensions, drove Germaine to furious rebellion.

School was her great escape. An obviously gifted pupil, she won a series of scholarships that allowed her to receive the best education a financially strapped Catholic education system could provide. At Star of the Sea, the convent of the Presentation Order of nuns where she completed the final four years of her education, she shone as the brightest pupil, soaking up knowledge, and was popular with the nuns and the other girls. She stopped believing in the nuns God, but she never lost the sense of spirituality they had instilled in her.

Her contemporaries memories of the tall figure of Germaine Greer striding around the campuses of her two Australian universities have become the stuff of legend. At the University of Melbourne, she completed an honours degree in English and French, and at the University of Sydney she wrote her masters thesis on Byron. She excelled in university theatre productions and gravitated to bohemian circles, namely the Drift in Melbourne and the Push in Sydney. The influence of the libertarian, anarchist philosophies and principles so fiercely argued by her Push friends and her lover of that time, Roelof Smilde, never left her.

From Sydney she won a Commonwealth Scholarship to Cambridge, where she wrote her doctoral thesis on love and marriage in Shakespeares comedies. Once again she was a star in university theatre, becoming one of the first women to be elected to the elite Footlights dramatic club. She worked furiously on her thesis, aiming to gain a post at an English university. This turned out to be Warwick, one of the newer universities that were starting to appear in England at that period, where she was appointed as an assistant lecturer in 1967.

No family or friends were present to support her when she proceeded to the dais of the ancient Cambridge Senate House to receive her PhD from the Vice-Chancellor in March 1968. She was also alone, in a different sense, in her three-week marriage to Paul du Feu, scholar turned labourer, which took place in May of the same year. She did not marry again and she has never sustained any long-term partnerships. She has many good friends but true intimacy has eluded her. I am unusually insecure in relationships, she told psychologist and television presenter Anthony Clare in 1989. Im a bolter, when things get difficult, I bolt...

Next page