COSIMA

WAGNER

THE LADY OF BAYREUTH

OLIVER HILMES

TRANSLATED BY STEWART SPENCER

YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW HAVEN AND LONDON

First published in English by Yale University Press in 2010

English language translation copyright 2010 Stewart Spencer

Originally published under the title Herrin des Hgels, Das Leben der Cosima Wagner by Oliver Hilmes 2007 by Siedler Verlag, a division of Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH, Munich.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office: sales.press@yale.edu www.yalebooks.com

Europe Office: sales@yaleup.co.uk www.yaleup.co.uk

Set in Minion Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hilmes, Oliver.

[Herrin des Hgels. English]

Cosima Wagner: The Lady of Bayreuth / Oliver Hilmes; translated by

Stewart Spencer.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-300-15215-9 (cl: alk. paper)

1. Wagner, Cosima, 18371930. 2. Opera producers and directorsGermanyBayreuthBiography. 3. Wagner, Richard, 18131883. 4. Wagner family. 5. Bayreuther Festspiele. I. Title.

ML429.W133H5513 2010

782.1092dc22

[B]

2009038775

A catalogue record is available for this book from the British Library

The translation of this work was funded by Geisteswissenschaften International Translation Funding for Humanities and Social Sciences from Germany, a joint initiative of the Fritz Thyssen Foundation, the German Federal Foreign Office, the collecting society VG WORT and the Brsenverein des Deutschen Buchhandels (German Publishers & Booksellers Association).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Whatever she was resolved should never see the cold light of day was doomed to remain forever locked away in Stygian archival gloom.

MAXIMILIAN HARDEN ON COSIMA WAGNER (1914)

Contents

Annes de Plerinage

The Joys of Love

The Sorrows of Love

Years of Happiness

The Princess

Brainwashing

Changes

From Bad to Worse?

Self-deception

A Journey into the Future

Coffee Mornings in Berlin

Storm Clouds

On the Run

Redemption

Last-minute Panic

Tristan and Isolde

Power and Influence

Intrigues in Munich

Involuntary Exile

Decisions

Guilt and Atonement

Human, All Too human

The Early Reich

Daily Life in Wahnfried

First Night

An Uncertain Future

Mephisto Waltz

Death in Venice

Trials and Tribulations

Friends and Assistants

Light and Shade

Crocodile Tears

A Change of Direction

The Year of the Three Kaisers

The Bayreuth Circle

Family Planning

Oedipus Rex?

La Grande Dame

Gone to the Dogs

Parsifal Mania

Iconoclasm

Regime Change

Rabble

Escalation

Dusk Falls on the Royalties

Tutte le Corde

World Conflagration

Life During the First World War

An Austrian in Bayreuth

A Living Monument

Finale Lamentoso

Prologue

B ayreuth in midsummer: a white-haired Wolfgang Wagner can be seen standing next to his wife, Gudrun, and their daughter, Katharina, in front of the Festspielhaus, while themes from his grandfathers operas waft down from the open-air balcony and women in long dresses and men in dinner jackets mill all around the theatre. The international press has also assembled here. Music critics from all over the world are filing reports on the performances for their readers at home, and television crews are on hand to film the offstage spectacle. Did you see last years Parsifal? visitors can be heard whispering. What did you think of Schlingensiefs production? The prominent guests are now beginning to arrive. Black and silver-grey limousines drive up and stop at a long red carpet that leads straight into the theatre. The countless onlookers, all standing at a respectful distance, watch as the federal chancellor, Angela Merkel, arrives with her husband, followed by the Bavarian prime minister, Edmund Stoiber, and his wife Karin. Also in evidence are Claudia Roth; Guido Westerwelle; the minister for health, Ulla Schmidt, and her cabinet colleague Ursula von der Leyen; two former German presidents, Walter Scheel and Roman Herzog; the ambassadors of Italy, Japan and France; and sundry local dignitaries.

This was the scene in 2006, but the description could apply to any year: the cast may change, but the production remains the same. While the brass players on the balcony intone a motif from Der fliegende Hollnder, the countless photographers call out the names of their subjects: Foreign Minister, could you turn this way? Hans-Dietrich Genscher bestows a friendly smile on the cameras. Frau von der Leyen, whats your husband called? Heiko. Not to be outdone by so many prominent politicians, the world of show business is no less well represented: Margot Werner, Grit Boettcher, Roberto Blanco and Thomas Gottschalk make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth almost every summer. Their number used to include the eccentric Munich fashion designer Rudolph Moshammer and his Yorkshire terrier, Daisy.

What are all these people doing here? Why have they come to this normally sleepy town in the Upper Franconian provinces? If Bayreuth has become the playground of high society, it is ultimately because of one woman alone: Cosima Wagner.

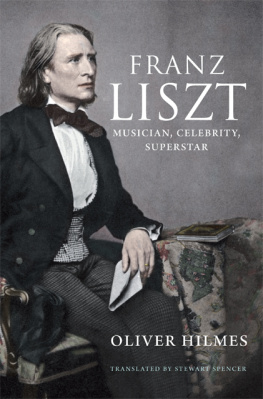

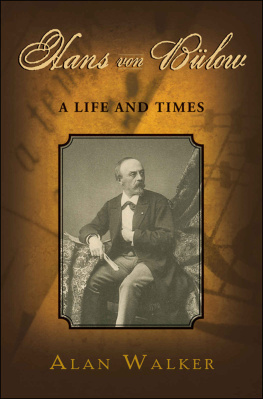

More or less everything about Cosima Wagner seems extraordinary. She was the illegitimate daughter of the leading pianist of the nineteenth century, Franz Liszt, and the French writer Marie dAgoult. She spent a parentless childhood in 1840s Paris under the iron rule of unloving governesses. Her life then took her to the Berlin of the 1850s, where she was introduced to her first husband, Hans von Blow, who was her fathers eccentric favourite pupil and, much later, the principal conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic. Even while they were still on their honeymoon, the Blows stopped off in Zurich and called on Richard Wagner, Blows friend of many years standing. Cosimas marriage to Blow was clearly a terrible mistake that ended in heart-rending tragedy following a scandal-fuelled episode in Munich. For years Cosima carried on an affair with Wagner behind her husbands back and had already borne him three children before she and Blow were divorced and she married Wagner, her elder by twenty-four years. It is an occupation I have not sought after or brought about myself, she wrote in her diary on 1 January 1869. Fate laid it upon me.

Cosimas first language was French. Her use of the German word Bettigung (occupation or activity) speaks volumes here, for her marriage with Wagner was no ordinary relationship. Rather, she saw the marriage as a mission. When Wagner died in 1883, Blow commented scornfully that his former wife should now marry Brahms, a joke that Cosima felt was in singularly poor taste. The only thing that Wagners forty-five-year-old widow wanted was to carry out what she regarded as her late husbands final wishes. Not baulking at even the most drastic measures, she cut off all her hair on the day of Wagners death and sewed it into a velvet cushion, which she then placed in his coffin. Her gesture was intended to show the world that she had no life beyond Wagners and that nothing should remind her contemporaries of her own individual identity. She spent the next forty-seven years successfully identifying with her late husbands person and works, so much so that the dead Meister seemed to live on in Cosima, who was duly dubbed the Meisterin. As a result, it is difficult even for the most hardened Wagnerians to form a clear picture of Cosimas personality. We may know what Wagner looked like as a person, but the outlines of his wifes physiognomy remain strangely blurred, and for the most part her personality disappears behind her self-appointed mission in life. But was her ego really so inextricably linked with Wagners?

Next page