To all those who have ever dared dream a big idea and then dedicated themselves to see it through, come what may.

It is not the critic who counts; not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles, or where the doer of deeds could have done them better. The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood; who strives valiantly; who errs, who comes short again and again, because there is no effort without error and shortcoming; but who does actually strive to do the deeds; who knows great enthusiasms, the great devotions; who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.

President Theodore Roosevelt

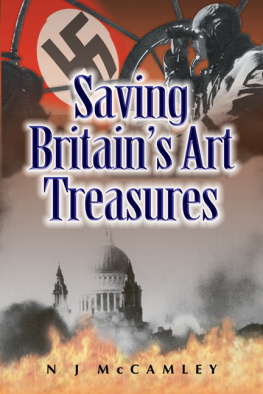

In wartime when the thoughts of men of fighting nations are concerned primarily with winning battles and the consequent fear, animosity, hatred, blood and death, it seems incongruous and inconsistent that the commanders of opposing armies should give attention to culture and the Fine Arts. Yet in both the Nazi-Fascist and Allied Armies, perhaps for the first time in history, there were men whose sole job it was to preserve the heritage and culture of nations being torn to shreds by the ravages of war. Italy was the first to know the men whose job it was to care for her cultural and artistic heritage in wartime.

MONUMENTS OFFICER CAPTAIN DEANE KELLER

CONTENTS

I moved to Florence, Italy, in 1996 and lived there for almost five years. At the time, I knew almost nothing about art or art history. My knowledge about World War II had come mostly from movies, a few books, and stories my fathera United States Marine Corps veteran of the war in the Pacificbegan sharing with our family near the end of his life. But my passion for learning, and interest in these subjects, made up for lost time. Florence soon became my classroom; Europe was my school. In recent years, after returning to the United States, I have dedicated my life to sharing with others the stories of the Monuments Men, the people responsible for saving so much of the worlds artistic heritage during a war that claimed sixty-five million lives. The United States played a leading role, one that should be a source of pride for all Americans.

Only during the course of my research for this book, nearly ten years after departing the city, did I discover how close I had been to the story of the Monuments Men. Our home in Bellosguardo, one of the hills overlooking Florence, had once been a part of the adjacent Villa dellOmbrellino, which suffered shellfire damage during the battle for the city. Cecil Pinsent, a noted landscape architect who served as a British Monuments officer, designed its Italian-style garden.

Torre di Bellosguardo, a hotel located directly behind our home, had been commandeered by the German forces responsible for destroying Florences magnificent bridges. Allies occupied the hotel after liberation. In fact, many of the places mentioned in this book are sites I frequented while living in Florence, unaware of the role they would later play in the writing of this book. In my research, I discovered that the Tuscan treasures at one point had been destined for St. Moritz, Switzerlanda special place in my life, and one where I wrote a large portion of this manuscript. This reminded me of something a close friend of Monuments officer Deane Keller once said: Life is full of mysteries in which unfathomable forces produce mystical results.

My journey has taken me from the Ponte Vecchio in Florencewhere I first wondered how so many of Europes great works of art survived World War II, and who saved themto Washington, DC, where, on June 6, 2007, members of Congress passed a joint resolution that for the first time honored the service of the Monuments Men and women. Five months later, I stood beside four of those heroes in the East Room of the White House to accept, on behalf of the Monuments Men Foundation, the National Humanities Medal from the President of the United States.

Forty-eight men and women ultimately served with the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section in the Mediterranean theater (including Greece and North Africa). (A complete list of their names appears at the end of this book). Regrettably, only one of the Monuments Men who served in Italy, artist Salvatore Scarpitta, was still alive by the time of my involvement. My inability to include more of these heroes stories, including his, is in no way a reflection on the merit of their wartime contributions or experiences.

I first met and interviewed Scarpitta on October 31, 2006. Although quite ill, Salvatore was still living at home, surrounded by some of the art he had created. We reminisced about Italy, then about his work as one of the late entrants into Monuments service. Like so many others I have interviewed, he apologized in advance for his failing memory, telling me, Im only sorry we didnt meet earlier. A few minutes spent examining photographs in my first book, Rescuing Da Vinci, prompted important observations:

I was a very critical young kid, but the attitude that we demonstrated was of terrific attachment to this history of the artists and of the people that respected their work.... I had a form of affection thats called love for these monuments. I felt that they represented real monuments of humanity, and they went through terrific tribulations.... So youll find in our studies and our work the attitude of people who want to preserve this heartbeat, and we did it very well, I thought.

Our emotional meeting took its toll on his energy. As I departed I said, Im going to come back and see you, so you better take care of yourself. He smiled. Im waiting for you... thank you, brother. Unfortunately, that subsequent meeting never occurred. Salvatore Scarpitta died almost six months later, on April 10, 2007. But his memory remains close at heart through his daughter, Lola Scarpitta Knapple, and her family, who, like the other children of these great men and women, want to celebrate the rich legacy of their loved ones.

Saving Italy is part of a much larger project. In June 2007, I established the Monuments Men Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving these heroes legacy and to reestablishing our nations leadership in the protection of cultural treasures during armed conflict. Public awareness of the Monuments Men and their achievements is essential to accomplishing that mission. I believe that this bookplus the permanent Monuments Men exhibition being developed for the Liberation Pavilion at The National World War II Museum in New Orleans, and the feature film based on my last book, The Monuments Men , being produced by Oscar-winner George Clooney and Grant Heslovwill introduce the extraordinary work of the Monuments Men to an even larger global audience. I also hope the increased visibility will engage the public in our search for hundreds of thousands of still-missing objects taken during the war and thus lead to further discoveries. Readers are encouraged to contact the Foundation if they have information or questions about the provenance of a particular objectpainting, document, or other cultural or historic itemremoved from Europe during or shortly after the war. For more information, please visit www.monumentsmenfoundation.org.

Next page