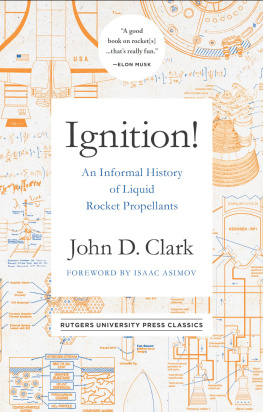

Ignition!

Figure 1. Engraving on plastic by Inga Pratt Clark, presented to Bob Border, Engineering Officer, NARTS, by the Propellant Division, 1959

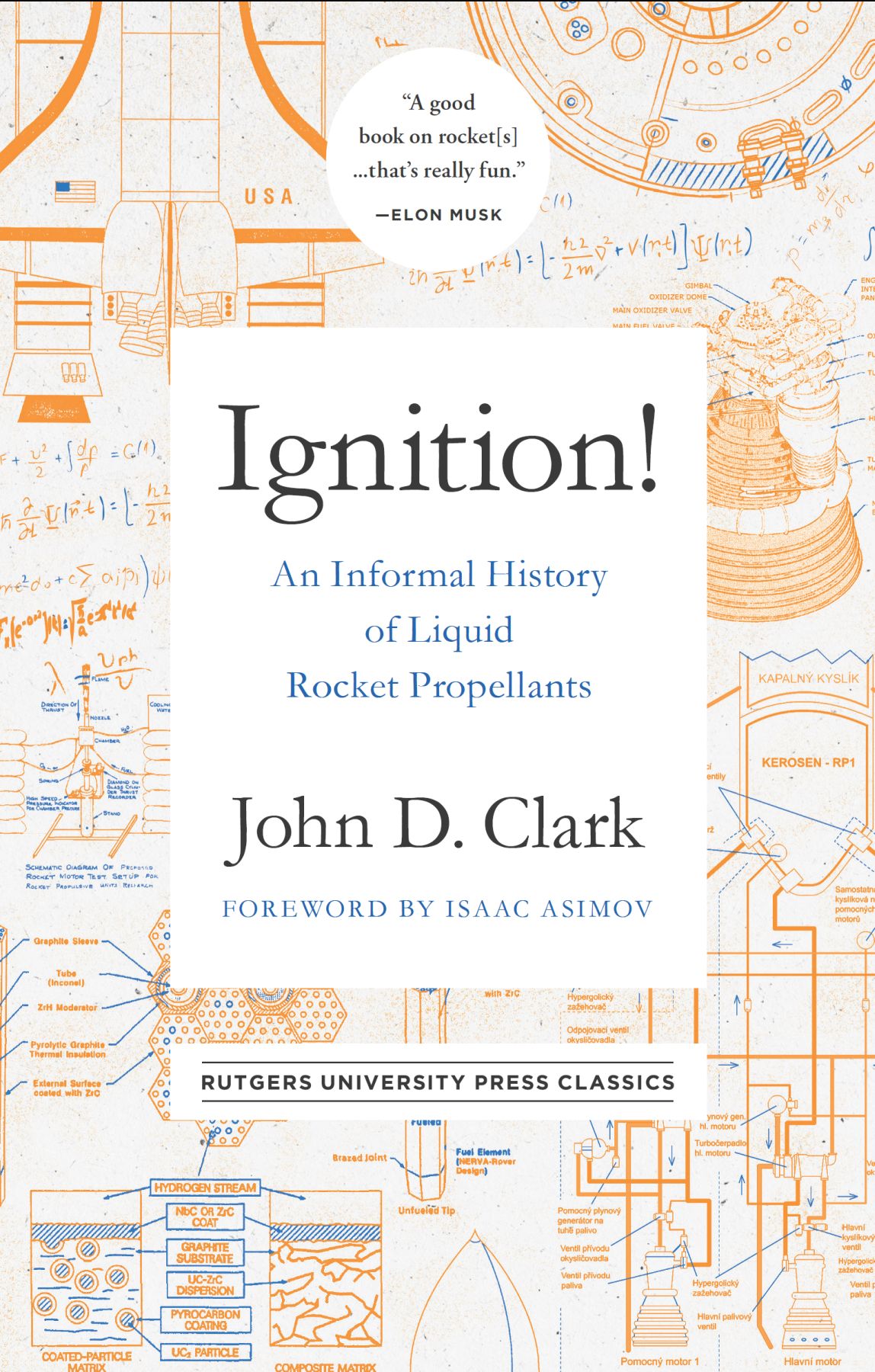

Figure 2. This is what a test firing should look like. Note the mach diamonds in the exhaust stream. U.S. Navy photo

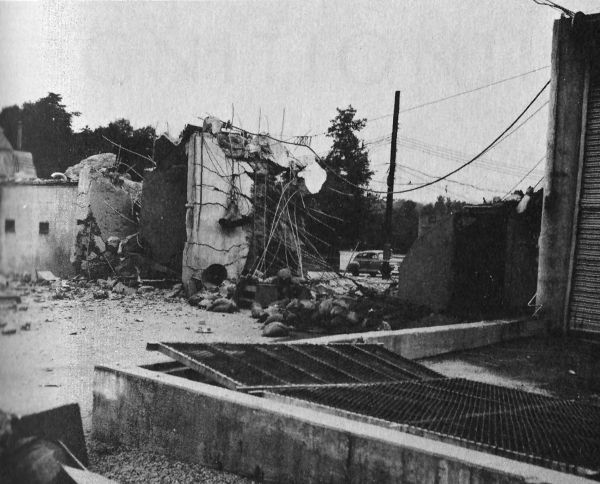

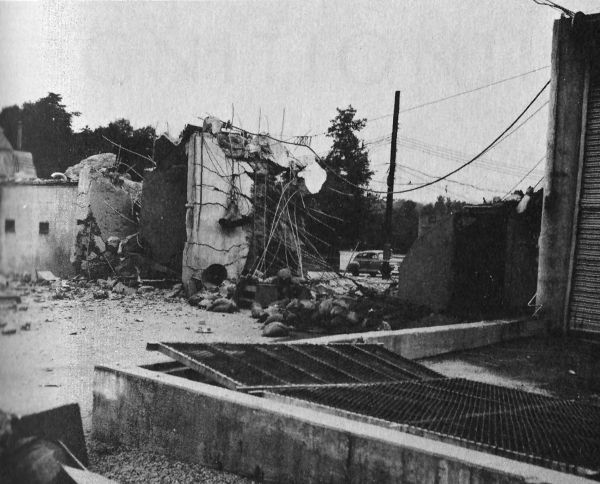

Figure 3. And this is what it may look like if something goes wrong. The same test cell, or its remains, is shown. U.S. Navy photo

Ignition!

An Informal History of Liquid Rocket Propellants

by John D. Clark

Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.

George Santayana

Rutgers University Press

New Brunswick, Newark, and Camden, New Jersey, and London

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Clark, John D. (John Drury), 19071988, author.

Title: Ignition! : an informal history of liquid rocket propellants / by John D. Clark.

Description: New Brunswick, New Jersey : Rutgers University Press, [2017] | Orignally published: New Brunswick, N.J. : Rutgers University Press, 1972. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017033845| ISBN 9780813507255 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813595832 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Liquid propellants. | Liquid propellantsHistory. | Rockets (Aeronautics)FuelHistory.

Classification: LCC TL785 .C53 2017 | DDC 629.47/522dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017033845

Copyright 2017 by Rutgers, the State University

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

This book is dedicated to my wife Inga, who heckled me into writing it with such wifely remarks as, You talk a hell of a fine history. Now set yourself down in front of the typewriterand write the damned thing!

Contents

by Isaac Asimov

I first met John in 1942 when I came to Philadelphia to live. Oh, I had known of him before. Back in 1937, he had published a pair of science fiction shorts, Minus Planet and Space Blister, which had hit me right between the eyes. The first one, in particular, was the earliest science fiction story I know of which dealt with anti-matter in realistic fashion.

Apparently, John was satisfied with that pair and didnt write any more s.f., kindly leaving room for lesser lights like myself.

In 1942, therefore, when I met him, I was ready to be awed. John, however, was not ready to awe. He was exactly what he has always been, completely friendly, completely self-unconscious, completely himself.

He was my friend when I needed friendship badly. America had just entered the war and I had come to Philadelphia to work for the Navy as a chemist. It was my first time away from home, ever, and I was barely twenty-two. I was utterly alone and his door was always open to me. I was frightened and he consoled me. I was sad and he cheered me.

For all his kindness, however, he could not always resist the impulse to take advantage of a greenhorn.

Every wall of his apartment was lined with books, floor to ceiling, and he loved displaying them to me. He explained that one wall was devoted to fiction, one to histories, one to books on military affairs and so on.

Here, he said, is the Bible. Then, with a solemn look on his face, he added, I have it in the fiction section, youll notice, under J.

Why J? I asked.

And John, delighted at the straight line, said, J for Jehovah!

But the years passed and our paths separated. The war ended and I returned to Columbia to go after my PhD (which John had already earned by the time I first met him) while he went into the happy business of designing rocket fuels.

Now it is clear that anyone working with rocket fuels is outstandingly mad. I dont mean garden-variety crazy or a merely raving lunatic. I mean a record-shattering exponent of far-out insanity.

There are, after all, some chemicals that explode shatteringly, some that flame ravenously, some that corrode hellishly, some that poison sneakily, and some that stink stenchily. As far as I know, though, only liquid rocket fuels have all these delightful properties combined into one delectable whole.

Well, John Clark worked with these miserable concoctions and survived all in one piece. Whats more he ran a laboratory for seventeen years that played footsie with these liquids from Hell and never had a time-lost accident.

My own theory is that he made a deal with the Almighty. In return for Divine protection, John agreed to take the Bible out of the fiction section.

So read this book. Youll find out plenty about John and all the other sky-high crackpots who were in the field with him and you may even get (as I did) a glimpse of the heroic excitement that seemed to make it reasonable to cuddle with death every waking momentto say nothing of learning a heck of a lot about the way in which the business of science is really conducted.

It is a story only John can tell so caustically well from the depths within.

Millions of words have been written about rocketry and space travel, and almost as many about the history and development of the rocket. But if anyone is curious about the parallel history and development of rocket propellantsthe fuels and the oxidizers that make them gohe will find that there is no book which will tell him what he wants to know. There are a few texts which describe the propellants currently in use, but nowhere can he learn why these and not something else fuel Saturn V or Titan II, or SS-9. In this book I have tried to make that information available, and to tell the story of the development of liquid rocket propellants: the who, and when, and where and how and why of their development. The story of solid propellants will have to be told by somebody else.

This is, in many ways, an auspicious moment for such a book. Liquid propellant research, active during the late 40s, the 50s, and the first half of the 60s, has tapered off to a trickle, and the time seems ripe for a summing up, while the people who did the work are still around to answer questions. Everyone whom I have asked for information has been more than cooperative, practically climbing into my lap and licking my face. I have been given reams of unofficial and quite priceless information, which would otherwise have perished with the memories of the givers. As one of them wrote to me, What an opportunity to bring out repressed hostilities! I agree.

My sources were many and various. Contractor and government agency progress (sometimes!) reports, published collections of papers presented at various meetings, the memories of participants in the story, intelligence reports; all have contributed. Since this is not a formal history, but an informal attempt by an active participant to tell the story as it happened, I havent attempted formal documentation. Particularly as in many cases such documentation would be embarrassingnot to say hazardous! Its not only newsmen who have to protect their sources.

Next page