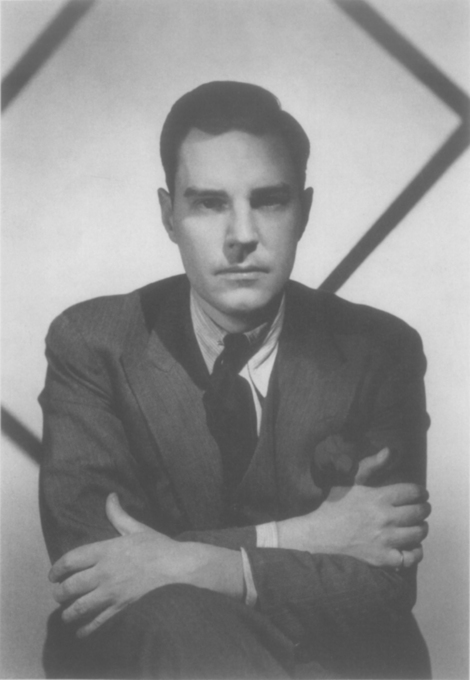

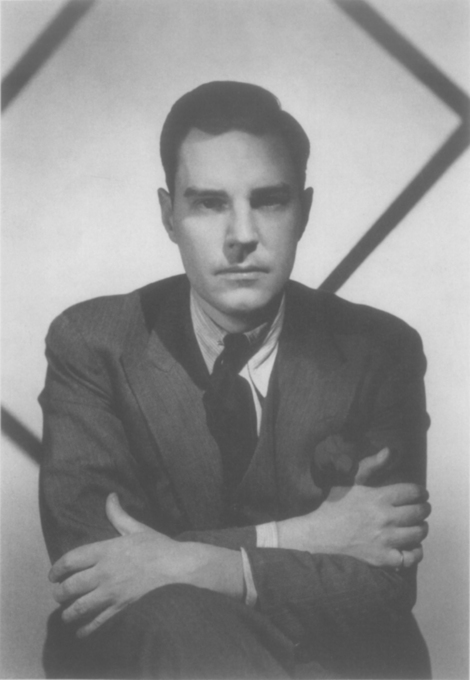

A. Everett Austin, Jr., 1936. Photograph by George Platt-Lynes

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2000 by Eugene R. Gaddis

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

www.aaknopf.com

Portions of this work were originally published in Ballet Review.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gaddis, Eugene R.

Magician of the modern : Chick Austin and the transformation of the arts in America /

by Eugene R. Gaddis.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-76124-8

1. Austin, Arthur Everett, 19001957. 2. Art museum directorsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. I. Title.

N576.H3 .G33 2000

700.92dc21

[B] 00-034905

v3.1

For Sally

and Nellie

Chick was a whole cultural movement in one man.

Virgil Thomson

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

The quotations in this book, particularly from personal correspondence, have been printed for the most part exactly as they were written, without the use of the term sic. (Chick Austin, for instance, regularly omitted the apostrophe from contractions.) In a few cases, however, such as where a proper name was misspelled, sic has been used. Obvious typographical errors in newspaper articles and other periodicals generally have been corrected.

Some anecdotes, especially those from Austins children, Sally and David Austin, were told to me in passing, or in different versions, or before this book was contemplated. Wherever this is the case, I have cited an approximate year instead of an exact date in the footnote.

PROLOGUE

The Navel of the World

O n the night of February 7, 1934, two hundred and forty people in evening dress descended into the Art Deco lobby of a subterranean theater, its curved walls of West African bubinga wood newly installed and still faintly pungent. Above them was the sleek white court of the most advanced museum building in America. It had just opened to the public with the countrys first comprehensive Picasso show, hung in third-floor galleries against walls that might have been lifted from the Bauhaus. Standing on the gleaming black marble floor of the lobby, amid the clicks and flashes of cameras, the audience milled noisily around, anticipating the climax of the evening. With an eye on the photographers, women in gowns designed for the occasion made discreet exits up one of the lobbys two staircases and conspicuous reappearances down the other. Gradually, the audience moved into the theater.

This celebration of the modern had drawn a glittering assemblage. They had come by private railway car, airplane, and Rolls-Royce; even, as one observer suggested, by jeweled pogo stick: Alexander Calder and Isamu Noguchi; Carl Van Vechten and Lucius Beebe; Buckminster Fuller and Clare Boothe; New Yorker cover artist Constantine Alajalov; Paul Rosenberg, Picassos dealer, from Paris; and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Having looked at nearly one hundred and fifty Picassos upstairs, they settled down to witness the first performance of an opera by Gertrude Stein and Virgil Thomson called Four Saints in Three Acts. It was directed by John Housemanhis first directing assignmentand choreographed by Frederick Ashton, making his American professional debut.

Twenty minutes behind schedule, the curtains opened on a set made of colored cellophane, designed by the reclusive New York painter Florine Stettheimer. The singers and dancers, dressed in velvets, satins, silks, and lace, were African-Americanthe first all-black cast in an opera. With its cubist language, its unexpectedly tuneful music, and its playfully voluptuous dancing, the performance created a sensation. Cheering erupted at the final curtain and did not stop for half an hour. A week later, Four Saints in Three Acts headed for a history-making run on Broadway.

The few who attended the operas premiere, and the many who later imagined they did, would remember it as an exquisite, delightfully incomprehensible novelty. But a handful of sophisticates in the audience would look back to the twin heralds of the centurys artistic upheavalthe New York Armory show and the Paris premiere of Stravinskys Rite of Spring, both in 1913to describe its impact.

Improbably, the museum and the theater were not in a great cosmopolitan city, but in Hartford, Connecticut. For a moment, the insurance capital of the world had become the greatest risk taker in the country. The museum was the venerable Wadsworth Atheneum, Americas oldest public art museum, the steward of the J. Pierpont Morgan collection of ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman bronzes, and Meissen and Svres porcelains; the Wallace Nutting collection of Pilgrim furniture and household utensils; and pictures by a reassuringly familiar pantheon of American paintersJohn Singleton Copley, John Trumbull, Thomas Cole, and the Hudson River School. Only lately had it been transformed, as if by some mischievous spell, into a spearhead of the avant-garde.

The impresario of the evening, propelled to the stage at the insistence of the crowd, was the glamorous young director of the Atheneum, A. Everett Austin, Jr., known to nearly everyone as Chick. The slim, graceful figure taking a bow, with his playful blue eyes and brilliantined hair, a gardenia in the lapel of his dinner jacket, was handsome enough to have stepped from the silver screen or out of a Nol Coward play. Yet his achievements at thirty-three were more substantial than might have been guessed from his boyish good looks. By 1934 he had already produced Americas first great Italian baroque paintings exhibition, as well as its first surrealist show, in which Salvador Dals Persistence of Memory was seen for the first time in the United States. He and his friend Lincoln Kirstein, under the auspices of the Atheneum, had already engineered choreographer George Balanchines immigration to America. Before the year was out, he would present, in this same theater, the first public performances of Balanchines company, the forerunner of the New York City Ballet. And it was he who had fought and badgered his architects into designing the interiors of the Atheneums new building, the Avery Memorial,

Chick Austin embodied the cultural revolution that swept the United States between the two wars. He also helped make it happen. Seeing all art as alive in the present moment, he could look with equal keenness back to the seventeenth century, its sensual splendors still on the verge of rediscovery, and forward to the very edge of artistic experimentation. His eye for quality, and his courage to promote the unfamiliar, were not surpassed in his time.

In the rarefied world of old-master connoisseurs and crusaders for the avant-garde, such moving spirits have not often been known to the public whose tastes they have shaped. But to the tiny elite that directed the flow of art in the momentous years of the 1930s, Chick Austin became almost a legend. He was the spark, the most incandescent tastemaker of them all. Painter, teacher, tailor, superlative cook, actor, magician, creator of costumes and setshe seemed prodigally gifted. In 1944, when Austins Hartford career came to an end, a dismayed Alfred Barr, the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, would tell him: But you did things sooner and more brilliantly than anyone.