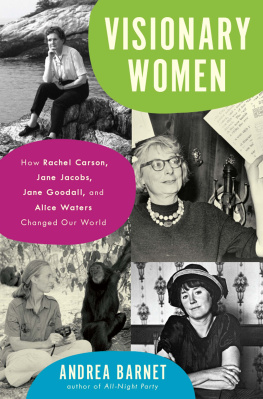

Barnet - Visionary Women

Here you can read online Barnet - Visionary Women full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018, publisher: HarperCollinsPublishers, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Visionary Women

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollinsPublishers

- Genre:

- Year:2018

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Visionary Women: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Visionary Women" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Visionary Women — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Visionary Women" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

for KIT and PHILIPPA

The grounds for hope are in the shadows, in the people who are inventing the world while no one looks, who themselves dont know yet whether they will have any effect.

REBECCA SOLNIT

Like the standing wave in front of a rock in a fast-moving stream, a city is a pattern in time.

JOHN HOLLAND

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.

JOHN MUIR

The boy builds us a fire out of pinecones, puts on a kettle, and makes us tea. Then he produces a small piece of cheese and painstakingly cuts it into even smaller pieces, which he offers us gravely....

He has given us everything he has, and he has done this with absolutely no expectation of anything in return. A small miracle of trust, and a lesson in hospitality that changed my life.

ALICE WATERS

Revolutions are sometimes sparked by unexpected characters, outliers whose excellence and originality, driving energy, and perseverance confound expectations. But these characters, it should be added, are rarely women, especially women who seemingly emerge from out of the blue, full-blown, defiantly themselves. This is the story of four remarkable women who changed the way we think about the world: four women linked not by friendship, or age, or even their fields, but by their monumental cultural impact, and the frequent, often surprising parallels in their thinking. All but one wrote iconic books that ignited social movements; all were green thinkers before the word had entered our vocabulary; all opposed the cultures blind obeisance to technology, seeing in its reckless quest to conquer and counterfeit nature an arrogant and deadly path forward. And all found their political voices in the 1960s, becoming a kind of true north for the gathering counterculture, who heard their call to arms and drew upon their ideas and their activism for their own.

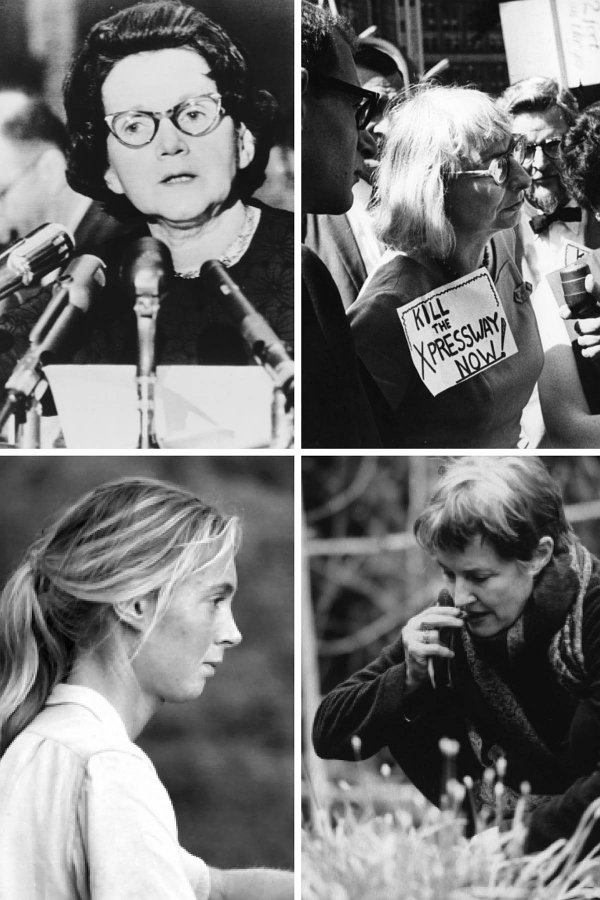

They are Rachel Carson, who published Silent Spring in 1962 at age fifty-five, giving birth to the environmental movement; Jane Jacobs, in her forties in 1961 when she saved Greenwich Village from the wrecking ball and published The Death and Life of GreatAmerican Cities, spawning a new consciousness about organized complexity and the life of cities; Jane Goodall, who in 1960 at age twenty-six discovered chimps using tools, altering mankinds understanding of the animal world overnight; and Alice Waters, who had her epiphanies about food in France as a student in 1965, and opened fresh, local-food-serving Chez Panisse in Berkeley, California, six years later, kicking off the sustainable food movement.

Like many of us, I suspect, I knew something of these womens thinking long before I had read their books. Growing up in the 1950s, I remember the fogging trucks that prowled the leafy streets of our suburban Massachusetts neighborhood, discharging deadly clouds of pesticides meant to kill the bugs that lived among us. I remember that several of our neighbors, crackpots my father called them, were building bomb shelters in their backyards, the idea being that they would somehow survive a nuclear attack in these homegrown bunkers. It was a notion, my father soberly explained, that was nonsense, without wading into the larger issue, which was that technology untethered from morality had a lethal, doomsday edge. At school there were nuclear drills: I recall lining up in our grade school corridors and then returning to our desks to practice duck-and-cover maneuvers, as if crouching under ones desk would be a sufficient response to an atomic event. My point is that even from a childs point of view, there was a certain peril, and a certain degree of willful denial that permeated the air of the 1950s. And as I would later discover in reading Silent Spring, it was this peril and purposeful avoidance of inconvenient truths that Carson was able to use to such powerful effect in her searing expos of the identical, equally deadly dangers of chemical pesticides, exploding public complacency almost overnight.

I remember the awfulness of the food during the fifties too, the occasional TV dinner my mother served. My sister and I didnt like them. The food was gluey and tasteless we thought. Though we did secretly like the way the little foil trays separated each foodstuff into a neat compartment. McDonalds was beginning to appear in the landscape by then. I dont specifically remember stopping at one, but I do remember my mother marveling at the bargain-basement price for a burgerjust nineteen cents, she said. And that the food was standardized, even to the point that the mustard and pickles had already been added. The kitchen was a mechanized assembly line; even the patties were made by a machine.

Later, long before I had read Jane Jacobss Death and Life, I remember driving into Cambridge with my father, passing a bank of bleak public housing towers along the way, feeling their anomie from the carthere were no people anywhereand then arriving in bustling Cambridge. I liked the narrow, winding streets immediately; the beautiful old-brick buildings there; the crowded one-of-a-kind bookstores and steamy coffee shops. I didnt know Jane Jacobs had written about the virtues of just such a human-scaled neighborhood; that she had used her own tatty block in Greenwich Village, where people stopped and talked, where even strangers looked out for one another, as a contrast to these sterile, government-engineered housing projects, which, amputated as they were from the body of the city, were socially dead, leached of the street life that connected a community, the incidental public spaces that served as social moorings.

Being a kid, of course, I couldnt see the lines of connection between all these things: engineered housing, wartime chemicals, industrialized agriculture, manufactured food. I didnt know that they were actually different faces of the same problem, part of the same cultural push to bend nature and natural systems to serve mankinds ends.

It wouldnt be until I was in college, in the 1970s, that I understood the extent to which much of what was passed off as food in the average supermarket had been manipulated to the point that it wasnt really food at all, but rather the spawn of some food technologist working in a gleaming chemistry lab somewhere. Or knew that the residues of industrial endeavors were turning up housing projects routinely pushed by urban planners, went beyond personal taste, that there were solid, sensible explanations behind these visceral responses.

By then I had joined my generation in its growing aversion to the technocratic direction of American life; its repudiation of Americas war machine; its protest against the chemicalization of food and farming; its alarm over the plunder of nature, and the parallel plunder of Americas cities; its quest for social justice and local solutions; its worry over the loss of place and community. I believed, inoculated with the arrogance of youth, but also as conventional history would have it, that these ideas had begun with us, with the counterculture.

Yet returning to that time, and to these four visionary women, I saw how little for which their innovations were designed.

There is a fifth woman, it perhaps should be added, who would seem to be a natural addition to this iconic group: Betty Friedan, who, in 1963, a year after the appearance of Silent Spring, published The Feminine Mystique, launching the modern womens movement. And in many respects Friedan does belong with this revolutionary band, but for one difference. While Carson, Jacobs, Goodall, and Waters were all trying to conserve endangered aspects of the culture, Friedan was trying to blow it apart wholecloth, seeing the system as it stood as pinching to the female psyche. While the other four were trying to preserve and restore systems they saw as threatened, Friedan was trying to dismantle a profoundly unjust one. Which is to say they were green thinkers, while Friedan was not.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Visionary Women»

Look at similar books to Visionary Women. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Visionary Women and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.