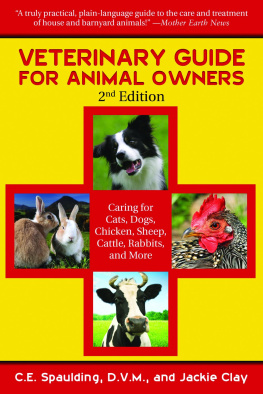

This is a rite of passage memoir, as well as an account of childhood in a vanished world. Phyllida Barstow weaves a refreshingly candid account of her developing personality into the fabric of the kind of eccentric, rural, educated upbringing that we seem too nervously conformist to give our children nowadays. The personalities are vibrant, from parents through sibling to sheepdogs and a succession of beloved ponies; and the arduous life on a Welsh farm is interleaved with civilising spells in seductive France, and the extraordinary rituals of the London season, especially for a girl whose heart lay more in dog baskets than handbags.

It is a book carried along by the authors own energy and appetite for life, and written with the clarity and elegance of someone who knows what they are doing.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR broke out just before I was two years old, and my first plunge into the dark soup of early consciousness in search of a flashback of memory finds me lying in a rumpled nest of clothes and rugs on the back seat of a car on a hot afternoon, thirsty and sticky, looking up into the anxious eyes of our nanny, Celia, shoe-horned into the luggage compartment among the suitcases and longing, like me, for the journey to end.

She was beautiful, gentle and beloved, and though there was no getting away from her strong personal aroma I knew exactly how she was feeling, tired of being cooped up and jolted about, but also like me, uneasily aware of tension emanating from the front seats, where my mother and brother were arguing over the map. She knew as well as I did that wed better keep quiet because any complaint was liable to provoke an explosion. When I had begun to whine some time back I had been told in no uncertain terms to shut up and go to sleep, but how could I when their voices were getting ever louder and snappier?

That cant be right, Mummy exclaimed.

It is! Im sure it is, insisted Gerry, on the brink of tears.

But weve tried that way already.

We didnt go far enough. Theres another turning,

There isnt.

Then were lost, said Gerry gloomily, and the word hung in the air with a dreadful finality. I wanted to cry, but knew it would be a mistake to attract attention. So long as Celia and I kept quiet, we wouldnt be what? Blamed? Shouted at? There was nothing either of us could do to improve the situation. The safest option was to keep a low profile.

For the past eternity, it seemed, the car had been moving in short spurts then halting, reversing, making about-turns and sudden changes of direction, but now it had been stationary for several minutes although the engine went on girning away, puffing out evil fumes. Sprawled on the back seat, I could see sky and trees and a signpost leaning drunkenly and I was dimly aware that it would be a calamity if the engine stopped. There was something wrong with the battery. Only that morning it had taken several men to push the car downhill before Mummy let in the clutch with a jolt and, calling Were off! had driven jerkily away from the hotel where wed spent the night. Now the sun was beating on the roof, the heat in the back was building up and along with the thermometer, tempers were rising.

As soon as the long-expected, long-dreaded war broke out, the even tenor of our nursery routine in London meals, walks in the park, play with parents, bath, bed had become unsettled, as nannies and nursery-maids came and went. Gerry and I never knew who would be looking after us next. Mummy volunteered for the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY) and became an ambulance driver. Daddy put his legal career on hold and, being already a territorial captain in the Honourable Artillery Company, was soon appointed major in the 12th Regiment (HAC) Royal Horse Artillery, guarding vulnerable points in London.

By late summer of 1940, when my mother was expecting a third baby, she applied for a discharge from the FANY so that she, and we, could follow the drum, perching in a series of chilly and uncomfortable boarding houses as Daddys regiment was posted first to Hertfordshire and then to the East Coast, the car becoming more battered and our possessions more scattered with every move.

We were living at Skegness in what we called the Mungle Bungalow when news reached my mother of the British Expeditionary Forces retreat from Dunkirk. Fear of an immediate German invasion prompted the authorities either to remove roadside finger-posts or turn them the wrong way round in the hope of confusing the advancing enemy, and this well-meant initiative made a nightmare of our long slow cross-country journey from East Anglia to Chapel House, my grandparents house in Wales. Daddy and his regiment had vanished in conditions of secrecy without even saying goodbye, and Gerry, only two years older than me, was pitch-forked into the role of man of the family.

Along with the heat and the smell, I remember feeling hopeless and helpless as tension mounted in the front of the car, and the cowardly way I squeezed my eyes tight shut when Mummy asked, Hows Phylla? and Gerry peered over the back of his seat to report, Asleep, adding with a tinge of envy, Lucky thing. No doubt he wished he could shed his responsibilities as easily.

I lay doggo, hoping to escape further notice, feeling a strong bond of sympathy for Celia, though our immediate needs were different. I was longing for a drink, while she was bursting to be milked, but we were both scared of triggering one of Mummys sudden explosions. Patience was never among my mothers many virtues, and at this moment she had enough fears and frustrations to justify an outburst of wrath.

With my father, along with most men of fighting age, in uniform, swept up in the war machine that was stuttering fitfully into action, her own future must have looked bleak and uncertain, and although she was good at giving a positive spin to circumstances looking on the bright side, as she would have said it cant have helped to know that Daddys new life showed every sign being much more dramatic and enjoyable than hers.

This was not only unfair; it also upset the dynamics of their marriage, pushing each of them into an unfamiliar role. Hers was the quick, bold, enterprising spirit whose love of adventure verged on recklessness and whose threshold of boredom was correspondingly low, while my father, calm, steady, tolerant, good-humoured and nine years her senior had always acted as a brake on her impetuosity and gently teased her out of her wilder enthusiasms.

Now it was up to her to behave sensibly and responsibly virtues which she instinctively despised. Fun, along with food and petrol, was in short supply. The threat of a German invasion hung over the country like a black cloud and the whole family was tormented by anxiety about my fathers younger brother, Oliver, who had not been in touch since the retreat from Dunkirk.

At this pivotal and terrifying moment of English history, staying in the depths of the country to look after small children was an unappealing prospect, and now she couldnt even find the right road.

All right, well try your way, she said in an exasperated tone that boded ill for Gerry if he was wrong. The growl of the engine grew louder as she revved, the car jerked forward a few yards, and then to my dismay, it faltered, coughed a couple of times, and died.

Thank you, God, for a lovely day, said Mummy bitterly into the silence, and at that point my flash of recall cuts off as abruptly as an eyelid closing.

Did it happen? The memory is sharp and vivid, but even a cursory check casts doubts on certain points. For a start, could a three-year-old remember in such detail? Isnt it more likely that I have run several different journeys together and come up with a composite scenario? Certainly we did drive for three days across the breadth of the country during the blackout, with Gerry asking passers-by for directions because the signposts had been removed, but what about the goat? Would the hotels we stayed in have put her up too? Would there even have been room for her along with the suitcases and the rest of our clobber in BYK 2, our little Standard 9?

![Johnson - This boy: [a memoir of a childhood]](/uploads/posts/book/185323/thumbs/johnson-this-boy-a-memoir-of-a-childhood.jpg)