Detail left

Detail right

Prologue

On a mild Friday morning in September 1867, two well-dressed, middle-aged women sat on a bench in New York Citys Union Square Park, discussing money.

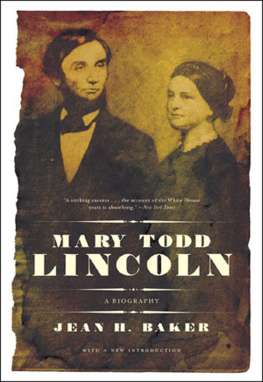

They were a curious pair. One was white; the other was not. The white woman was dressed in deep mourning, with her face hidden behind a heavy veil of black crepe. She was short and heavy-set and looked to be excited or agitated. When she spoke, which she did rapidly and almost steadily, she was unable to sit still, and she glanced around her frequently, as if checking to see that no one could overhear. But whenever she fell silent, her body seemed to slacken, her shoulders sink, and an air of despondency would come over her. She gave the appearance of being very much alone, despite the presence of her interested companion.

The second woman was also a fascinating study. She sat very still, listening, her back straight, her hands in her lap. Her face was handsome, with deep-set eyes, a firm mouth, strong nose, and a complexion that suggested she was of a mixed-race background. She wore her dark hair coiled in a braid on her head, and she was dressed as elegantly, though less richly and elaborately, than the woman beside her. At first glance, one would think her demeanor proud, even haughty. But a longer look would find in her composure the habit of waitingsilent, watchful, patient. She had the regal bearing of one who might have been a queen, but in fact, she was a mulatta who had been a slave.

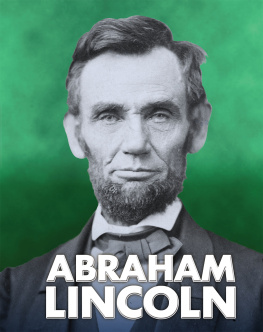

The first woman was Mary Todd Lincoln, the daughter of a wealthy Kentucky slaveholder, who had become a Presidents wife by throwing in her lot with the driven, self-schooled son of a poor white farmer. The second was Elizabeth Keckly, the illegitimate daughter of her Virginia master and his slave, who had bought her freedom and gone to Washington, where she had become the dressmaker and confidante to the Presidents aristocratic wife. At their first meeting, the day after Abraham Lincolns first inauguration, they had had to negotiate a fair price for Lizzys services. Now they were talking money again, only this time they were devising a moneymaking scheme intended to help them both, though it was Marys debts from overspending and her anxiety about poverty that spurred them on.

One might say they had changed places. At forty-nine, the former slave was a successful Washington businesswoman, but her companion, who would be forty-nine in December, was a traumatized, debt-ridden widow, living with her youngest surviving son in a genteel hotel in Chicago. Lizzy had continued to sew for Mary, who would even now accept only work done by Lizzys own hand, but the two had hardly seen one another for two years. Then one day in March, a determined Mary Lincoln wrote a letter to her friend: Now, Lizzie, I want to ask a favor of you. It is imperative that I should do something for my relief, and I want you to meet me in New York.

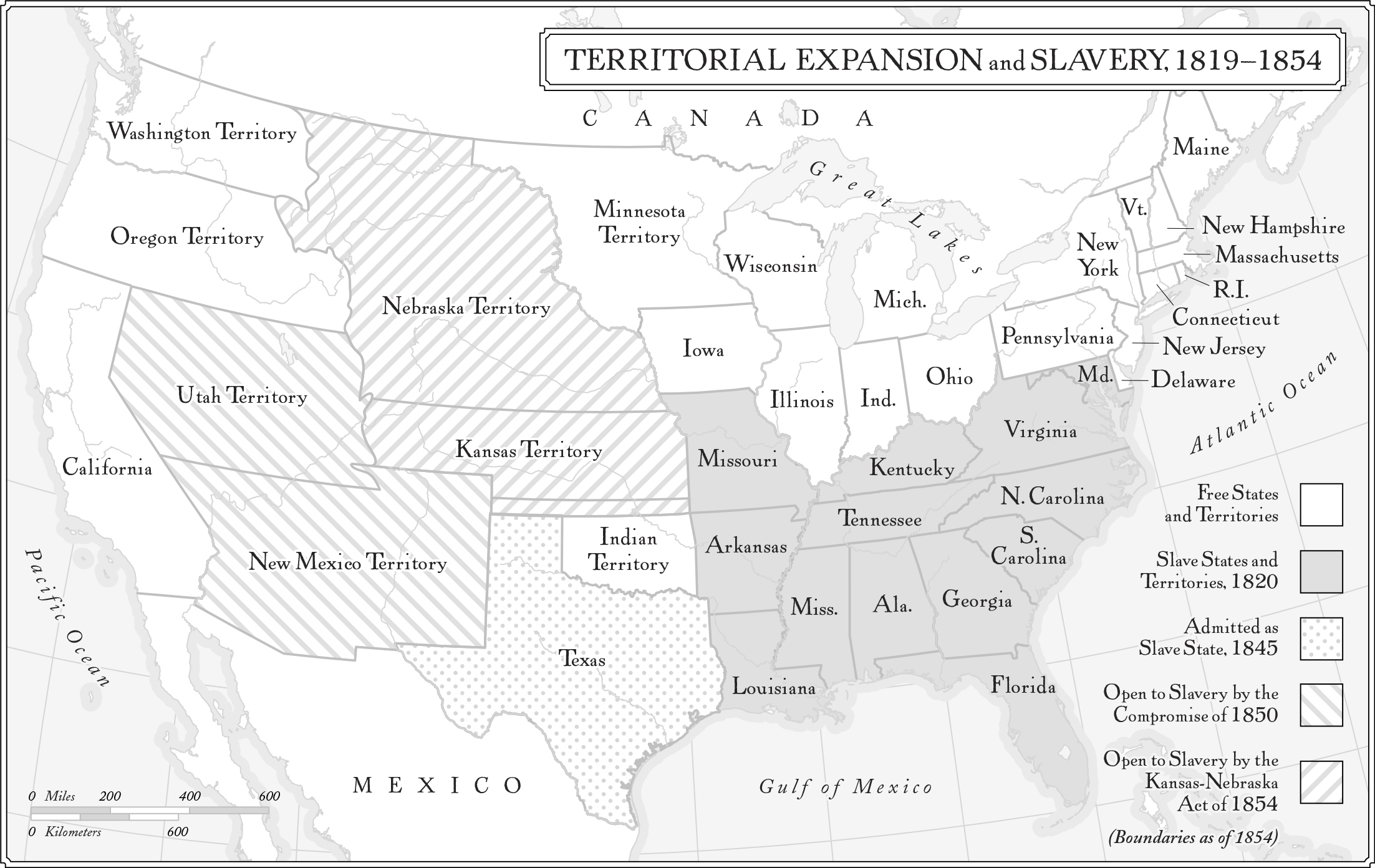

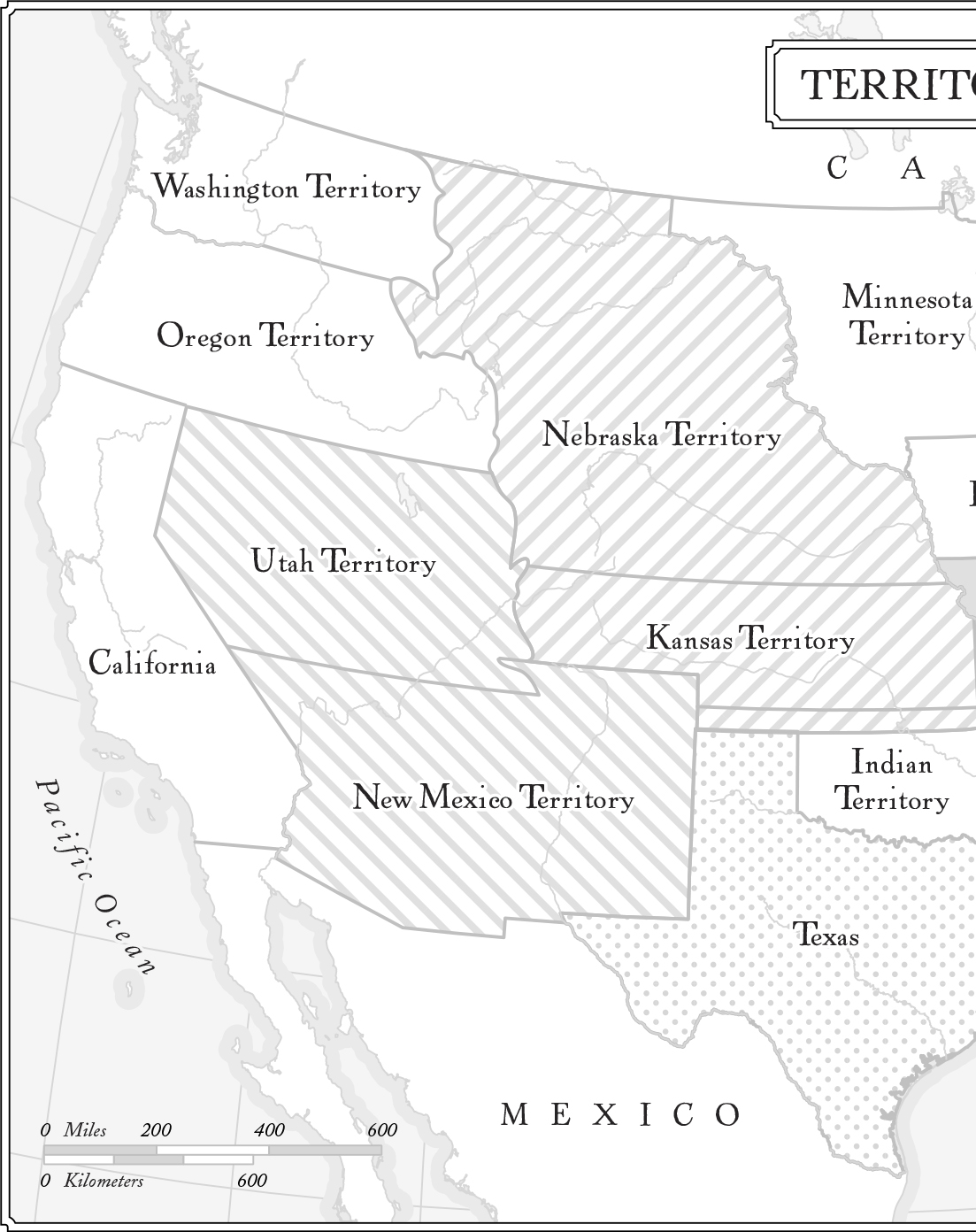

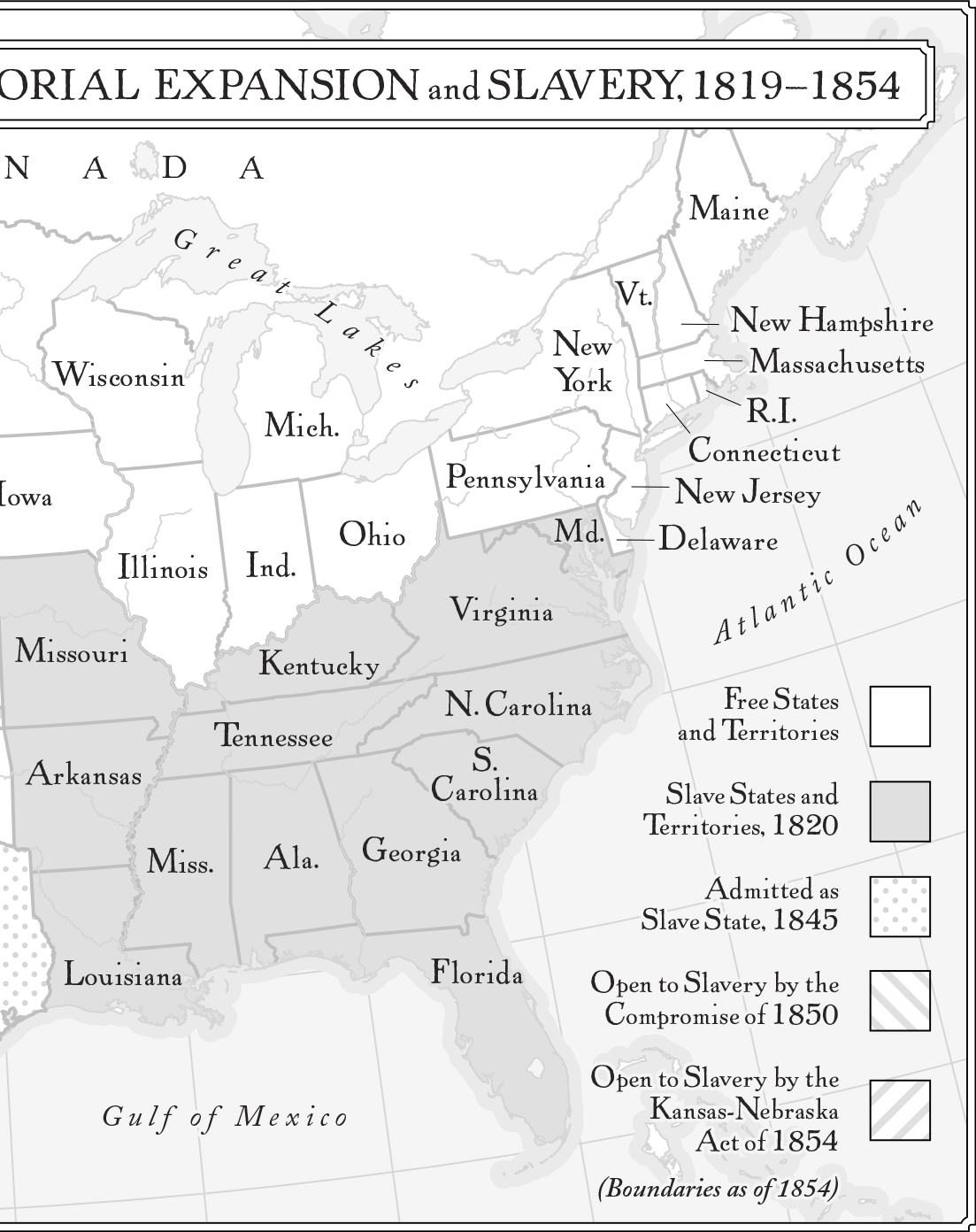

As they sat near the majestic equestrian statue of George Washington that dominated one end of the park, their heads inclined together in confidential conversation, the two women focused on the mundane details of what they intended to accomplish. And although their interests were decidedly mercantile, the conversation itself was a type of quiet revolution that Washington scarcely could have imagined. That two women should be devising a commercial transaction without the knowledge of male relatives or guardians was already a somewhat bold undertaking. But that one of them was a Presidents widow and the other a woman of African descent and a former slave was indeed a test of the possibilities of citizenship in the nation. Four generations earlier, many Americans believed that human enslavement was incompatible with their founding ideals of equality, liberty, and happiness for all, but only north of the Mason-Dixon line, the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania, was slavery abolished in their time. It took a war between the statesafter decades of westward expansion had made slavery an explosive issue, as two million square miles west of the Mississippi had to be allotted to Northern freedom or Southern slaveryto resolve the tragic contradiction inherent in the founding of the republic. To be sure, the end of slavery exposed fresh contradictions: if one asked her, the freedwoman Lizzy would have said that she felt less kinship with the Irish nursemaids who sat chatting nearby while their young charges played than with the lavishly attired Presidents widow by her side. And the widow would have said the same.

With retailers beginning to cram into the basements and parlor floors of the mansions and brownstones on the square and boardinghouses and hotels moving in, Union Square was slightly past its prime as the prestigious residential center of the city. Money was migrating northward: the wealthy were moving to Madison Square and Gramercy Park and developers were eyeing upper Manhattan and beyond. Vast emporiums and mansions rose along northern Fifth Avenue and would soon pass 52nd Street, where the abortionist Madame Restell had daringly built her palace in 1862. But Union Square was familiar territory for Mary Lincoln, who in her own heydayher proud, expansive early days as Mrs. Presidenthad bustled in and out of the fancy stores that lined the west side of lower Broadway in an exultation of shopping (then a relatively new verb), spending the $20,000 appropriation that Congress had granted to refurbish the shabby White House. Custom-made carpets, damask draperies, ornate furniture, and monogrammed china were ordered, packed, and sent to her new home in Washington. She also picked up several costly black point lace and camels hair and cashmere shawls, all exceedingly fashionable. Trailed by reporters, the lady made news with her high-flying tastes and lavish spending.

Those days were over. And after all that had happened, it was Lizzy Keckly who had proven herself to be Mary Lincolns closest, most durable confidante from her Washington days. I consider you my best living friend, Mary would write to her; and at the time, it was true, for there was no one else who would do what Mary was asking. Resourceful and energetic, imperious and needy, Mary had exhausted all the white people whose aid she could command or cajole. Yet she could be a shrewd assessor of character (that is, when vanity did not get in her way), and over the years she had come to appreciate Lizzys gifts; she knew that she could count on Lizzy to be discreet and to manage delicate situations, especially those involving well-heeled white folks. The plan to raise funds that Mary proposed to Lizzy was simple: they were to enlist a Broadway broker to sell off her old clothes and jewelry. Surely, there were many who would pay to own a little something that Mrs. Lincoln herself had worn. In summoning Lizzy, Mary Lincoln anticipated having the benefit of not only her companions sound advice and comforting approval, but also her assistance in carrying out the idea.